Paper is at the heart of an experimental device to study heart disease, researchers report.

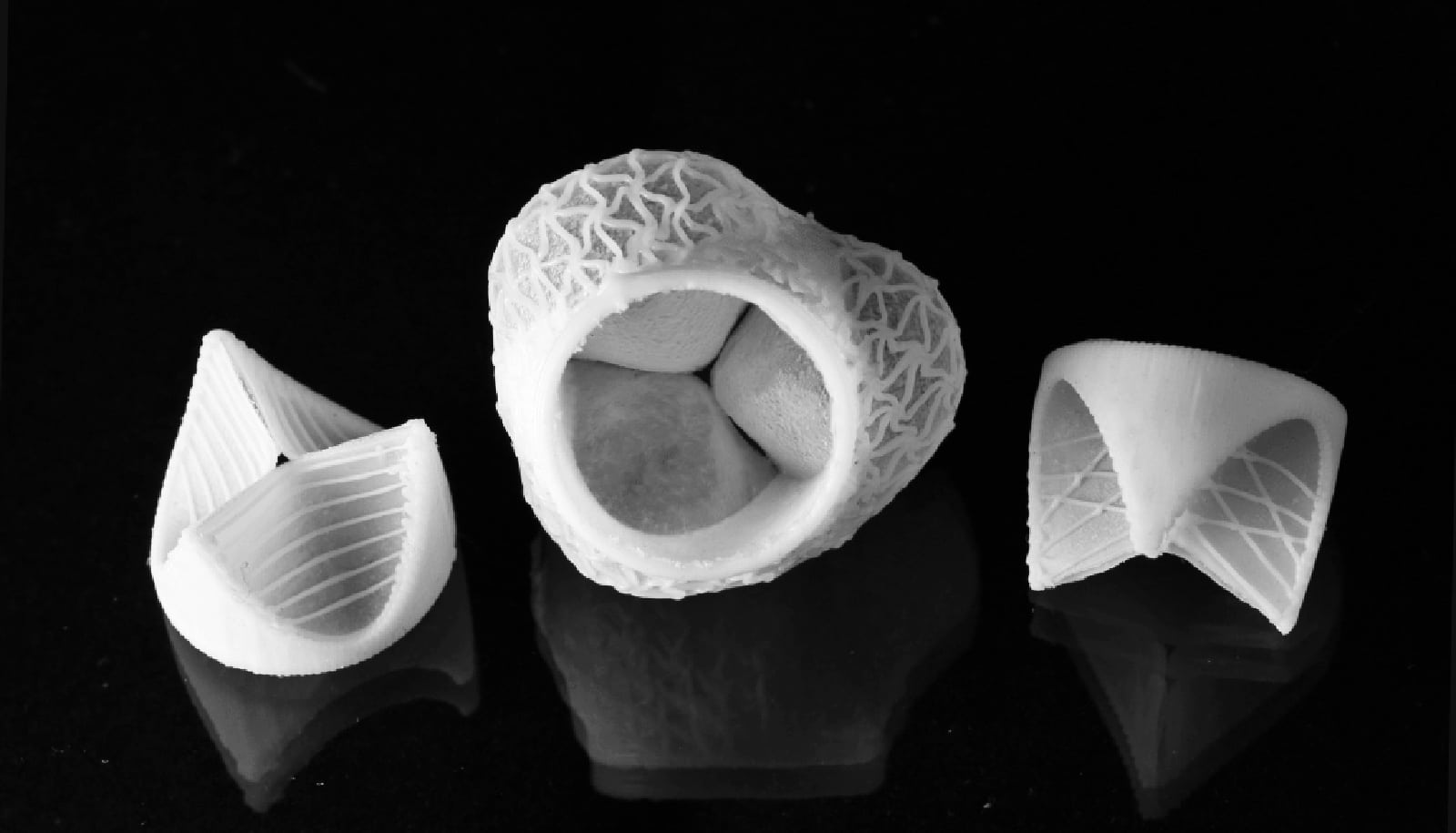

Researchers are using paper-based structures that mimic the layered nature of aortic valves, the tough, flexible tissues that keep blood flowing through the heart in one direction only. The devices allow the engineers to study in detail how calcifying diseases slow or stop hearts from functioning.

The research shows that collagen 1, a natural protein and a component of the valves’ fibrous extracellular matrix, appears to have a strong association with calcification when it is found outside its usual domain. Valves that calcium deposits harden are less flexible and lose their ability to seal the heart’s chambers.

Runaway collagen

“When tissues make a lot of excess type 1 collagen, it’s called fibrosis,” says Jane Grande-Allen, a professor of bioengineering and the chair of the bioengineering department at Rice University who directed the study with graduate student and lead author Madeline Monroe. “Fibrosis can happen in many types of tissues and it accompanies calcific aortic valve disease (CAVD). That doesn’t necessarily mean collagen will always cause CAVD, but it definitely drove the calcification-linked phenotype in the cells that we cultured.”

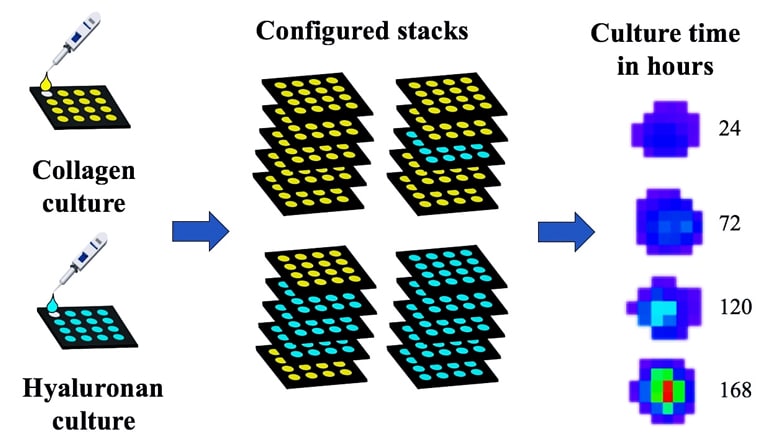

Collagen generally stays in the valve’s fibrosa layer, one of three in each of the three leaflets that make up an aortic valve. (The others layers are the spongiosa and ventricularis.) The researchers prepared paper layers to support heart valve cells embedded in either collagen or hyaluronan, and discovered that when collagen 1 proteins are present in multiple layers, the cells behave in a way that would ultimately lead to mineralized lesions.

Grande-Allen says the layers of extracellular matrix in a healthy aortic valve are well-defined. “In a more pathological state, the collagen isn’t localized,” she says. “It’s spread out. Our models suggest nonlocalized collagen could contribute to cell overexpression of these calcific factors.”

The researchers want to know how that happens. They needed a way to see how valve cells would react to collagen spreading through a three-dimensional tissue, and common filter paper turned out to be a suitable stand-in. What they made doesn’t look like a heart valve, but effectively acts like one to show how cells proliferate through a valve’s layers.

Mimicking heart disease

Heart valve disease can’t be treated with a pill yet, says Grande-Allen, who has studied valve disease for much of her career and reported on paper-based cultures in 2015. Current remedies often involve replacement of the valve with human or animal donor tissue or a mechanical valve. But the ability to accurately model and manipulate all the layers of a valve could help decipher the chemical transactions in heart disease. She says that may eventually lead to noninvasive medication.

“The first step has been to develop models that mimic the way the cells in valves behave,” Grande-Allen says. “The next step would be to see them actually calcify. Once that is in hand, we can start to test chemicals that would block that calcification process.”

The researchers took inspiration from the cells-in-gels-in-wells filter-paper cultures used at Harvard University to study hypoxia in lung cancer cells.

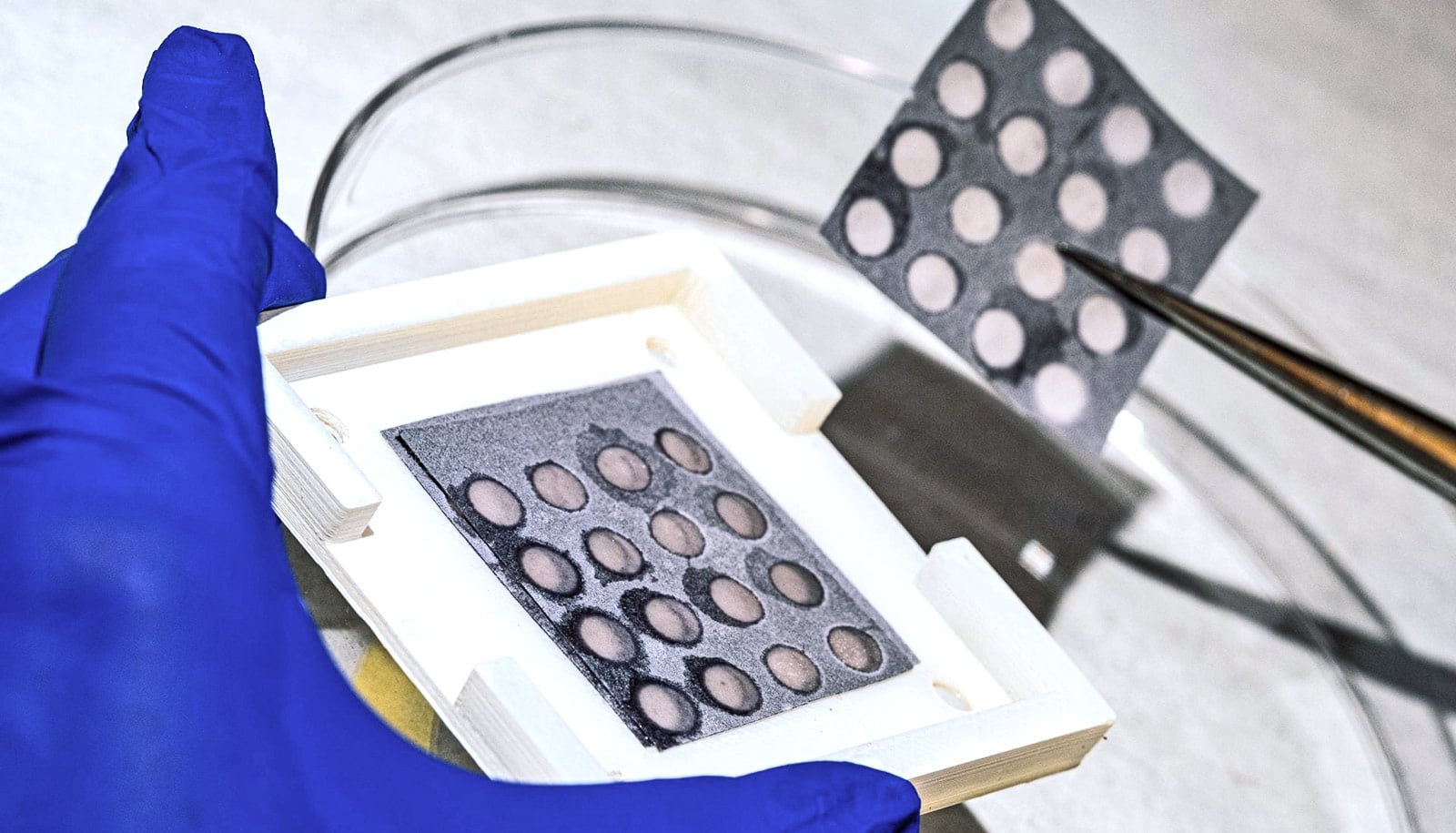

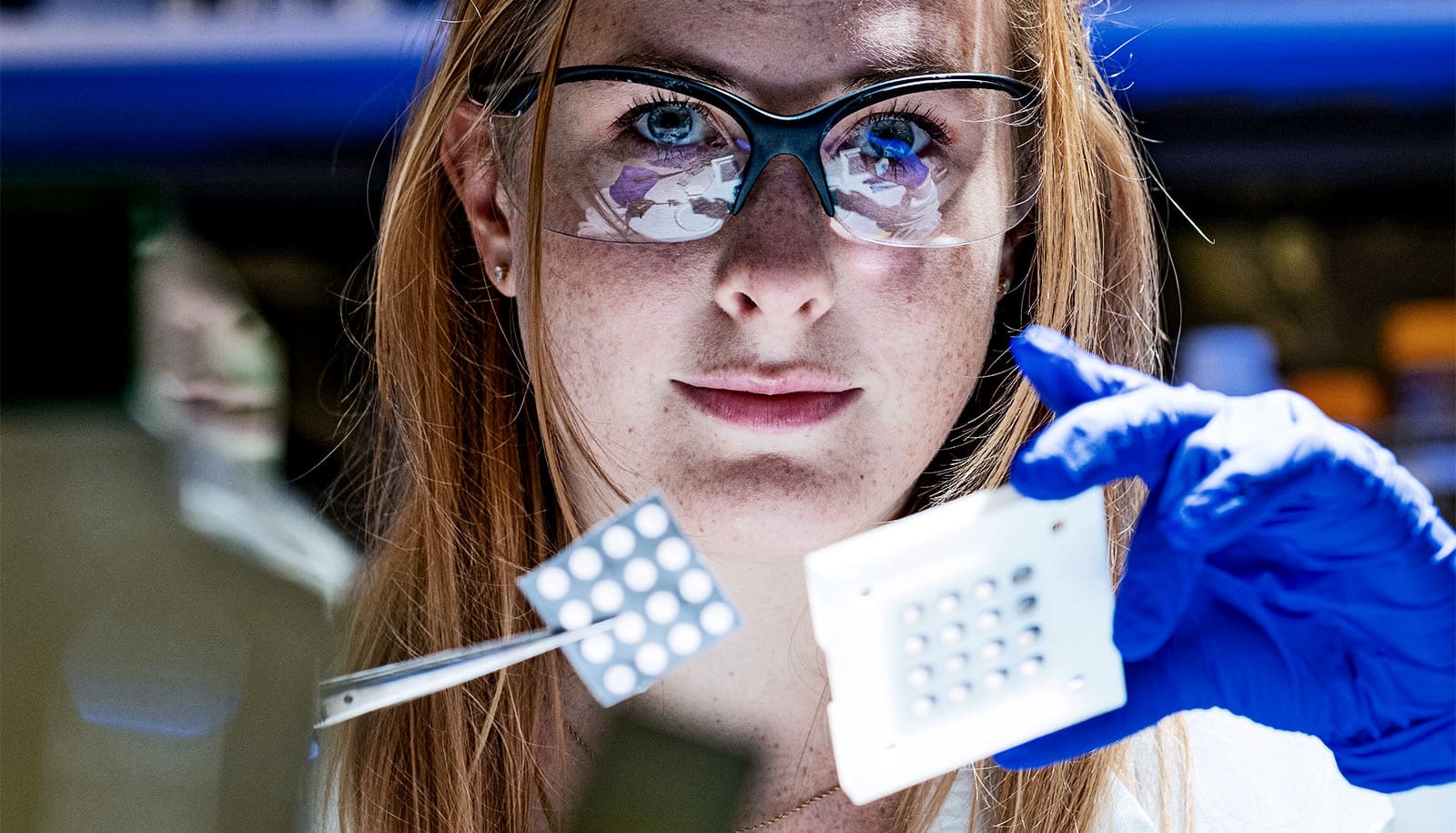

The lab started by 3D-printing polymer holders with arrays of holes. These held in place layers of paper that researchers had impregnated with a wax pattern to eliminate crosstalk between the open circles of filter paper. They then saturated the circles with various combinations of fibrous collagen 1, hyaluronan (normally found in the spongiosa layer), and millions of living heart cells, and pressed the sheets together within the holders.

“This modeling system gives us complete control over a lot of different variables,” Monroe says. “We were able to create distinct stacks with different compositions based on what components we put in each layer. We had stacks where all the layers were all hyaluronan, or all collagen, or heterogeneous stacks with both kinds of layers.

“That let us see if the cells behaved differently when there was an increase in the number of collagen layers,” she says.

Monroe assessed the cells’ behavior over time by analyzing the protein markers they expressed, particularly alpha smooth muscle actin (aSMA), a Runt-related transcription factor-2 (RunX2), and SRY-box 9 (Sox9), all of which are indicators for CAVD. Using a high-throughput staining and scanning method with the groups of wells allowed her to quickly gather data from dozens of structures.

The data let them see that valvular interstitial cells, the principal and normally stable aortic valve cell type, became more susceptible to osteogenesis—hardening—in the presence of more layers containing collagen protein.

“The paper model is ingenious for allowing us that versatility and flexibility,” Grande-Allen says. “I don’t know of another method that so easily allows us to put together different layers easily, culture the combinations together and then take them apart and analyze them so rapidly.”

The researchers detail their work in Acta Biomaterialia. The National Science Foundation and the American Heart Association supported the research.

Source: Rice University