Tests show a new harness makes surgical masks just as good as N95 masks in stopping aerosol droplets.

The easily manufactured adhesive silicone harness allows light surgical masks to match and sometimes exceed the federal safety standards for N95 and KN95 masks, the researchers say.

During the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers went looking for and found a way to make standard surgical masks better at keeping out small airborne droplets that might contain the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

A study detailing the work appears in JAMA Network Open. Jeannette Ingabire, a systems, synthetic and physical biology graduate student in the lab of Jacob Robinson, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering and of bioengineering at Rice University, led the study.

“N95s were hard to get at the time, so it seemed logical to improve the flimsy surgical masks you see in hospitals,” Robinson says. “Now, of course, good masks are easier to get, but you never know when our solution will be needed.”

The project began when coauthor Sahil Kapur, an assistant professor in the plastic surgery department at MD Anderson, approached colleagues with an idea for a harness to make surgical masks fit more snugly around the face.

Based on Kapur’s concept, Caleb Kemere, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering and of bioengineering at Rice, designed several concepts, tried them on himself, and determined they could be laser-cut from a single sheet of elastomer.

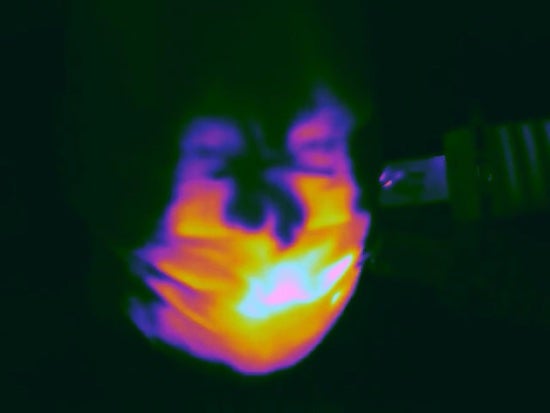

Ingabire and the team 3D-printed mannequin heads of different shapes and sizes as specified by federal regulations. Once they assured proper fit with the mannequins, Ingabire and Hannah McKenney, a Rice alumna now at MD Anderson, recruited more than three dozen COVID-negative volunteers from among “essential personnel” at the institutions to judge the masks for comfort and sit for airflow tests with an infrared camera.

The camera quickly revealed where air was leaking in and out of ill-fitting masks—most often near the nose and eyes—leading to a revision of the harness.

The team’s version 2.1 closed the gaps for most wearers by widening the harness along the slope of the nose while reducing the amount of material overall to preserve the wearer’s field of view. The rubbery harnesses give the mask more of the form of an N95, with better sealing than the surgical mask alone.

“That was a suggestion from clinicians at MD Anderson who told us if something is really big, it can interfere with a surgeon’s eyesight,” Ingabire says. “So the final version fits more snugly around your nose. If you want people to use something for a long time, it has to be comfortable.”

The revised harness/mask combo easily passed a “filtering facepiece respirator” evaluation that proved them to be 15 times better at stopping droplets than surgical masks alone. Though the masks themselves are single-use, the harnesses can be removed, sanitized, and used again, Ingabire says.

She says some of the volunteers were impressed enough to keep their harnesses.

“A few grabbed some,” she laughed. “When they saw they passed the same fit test they use to evaluate an N95 in a hospital, they said, ‘Can I have this?'”

Source: Rice University