More than 100 unpublished drawings by the German writer Franz Kafka are now available in a new book.

Most people know Franz Kafka for his written works such as The Metamorphosis, The Trial, and The Castle, yet he also drew vigorously. Until recently, only 40 of Kafka’s drawings had come to light.

When in 2019 a safe deposit box from a vault on Zurich’s Bahnhofstrasse was opened after years of legal wrangling, it revealed a huge surprise: in addition to manuscripts known to have been deposited there decades ago, were over a hundred previously unseen drawings.

Andreas Kilcher, professor of literature and cultural studies at ETH Zurich, is editor of the new book, Franz Kafka: The Drawings (Yale University Press, 2021).

Here, Kilcher answers questions about Kafka’s drawings:

The discovery of these drawings has been described as sensational. What in your view makes it so special?

Well, we thought we already knew everything about Kafka, so the fact that so many unseen drawings by a world-famous author have now surfaced is impressive. But to me, the drawings are astonishing too. Many of them are playful and humorous: they show us a much more cheerful side to Kafka.

So the newly discovered drawings are anything but “Kafkaesque”?

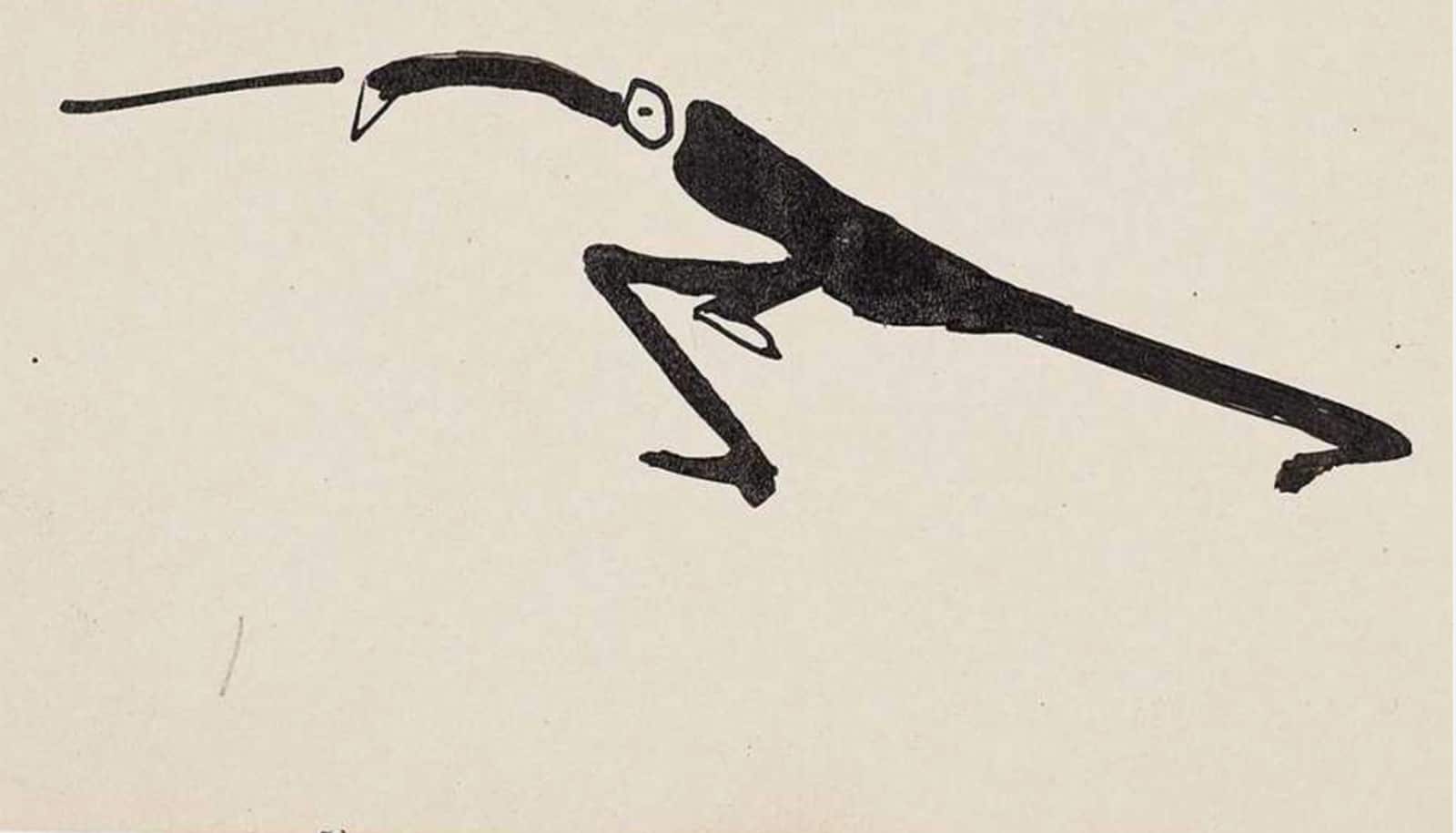

That’s not a term I particularly like, as it usually denotes an absurd situation. What we see in Kafka’s drawings is rather the playful and grotesque, the exaggerated and surreal—his sketches are rather like caricatures.

Do you have a favorite drawing?

It’s not easy to pick out one, as I like so many! But my vote would go to “Übermut des Reichtums” (“The Presumptuousness of Wealth”), which depicts two clearly wealthy ladies being served giant pheasants on oversized trays, while an orchestra on a stage plays in the background. Here it’s not just the scene which is overexuberant: the sketch also shows the presumptuousness of drawing in itself.

How come it is you who are publishing the drawings?

I’m very familiar with the rather fascinating saga of Kafka’s literary estate and have closely followed the legal dispute surrounding it. So I was pretty sure that the safe deposit boxes at UBS in Zurich, where his estate had been stored for decades, contained drawings as well as manuscripts. But while the manuscripts were all already known, we only knew a few of the drawings—and it was clear there were many more.

When the Zurich district court ruled in 2019 that the safes could be opened and their contents shipped to the National Library of Israel, I immediately traveled to Israel to look at the drawings with the prospect of editing them firmly in my mind. The extent and quality of the drawings astonished me.

It’s striking that the newly discovered drawings were all made between 1901 and 1907.

Yes, Kafka drew most intensely in his university years. And during that time, he not only drew, but was also keenly interested in art, studying art history for a semester and meeting several artists. Although after his studies Kafka was mainly active as a writer, drawing and art were a central part of his life. Yet he couldn’t take this interest to a professional level, so drawing took a back seat. But there are similarities between drawing and writing: both tend toward the imaginary; both are fragmentary and unfinished.

Have the new drawings changed the way you look at Kafka’s texts?

Very much so! The pictures made it clear to me just how sensitive Kafka is to everything visual, and this affects how he describes bodies, objects, and situations in his writing. Kafka understood the aesthetic power of images and used them consciously and skillfully. At the same time, I want to emphasize that his artwork stands in its own right; one shouldn’t jump to conclusions from the drawings to the texts and vice versa; nor should the drawings in any way be understood as illustrations to his written work.

Source: ETH Zurich