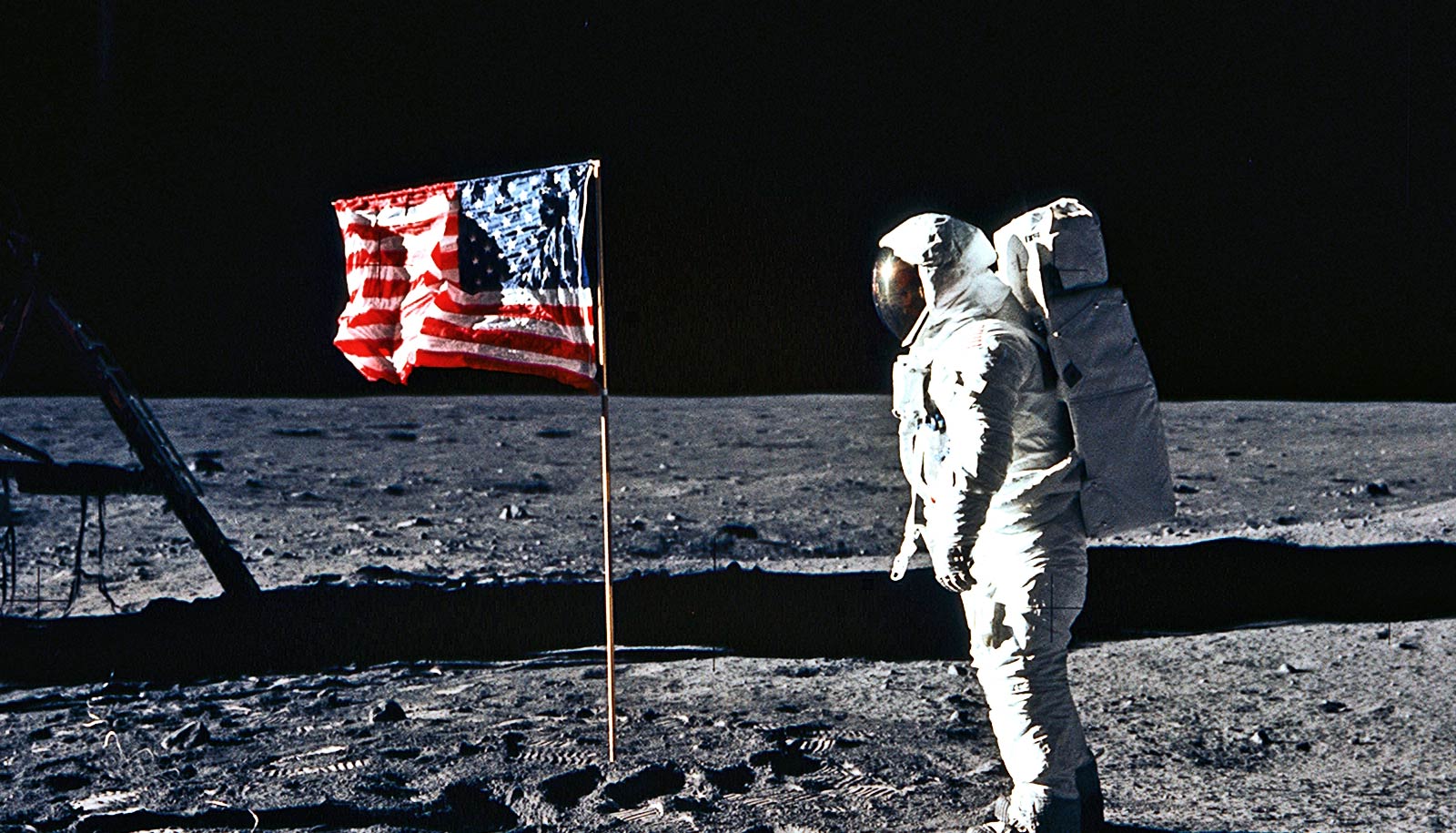

When Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin planted the United States flag on the moon 50 years ago on July 20, 1969, it represented a major feat of engineering, argues Annie Platoff.

“The flag on the moon is a great illustration of the fact that in space, nothing is simple,” says Platoff, a librarian at the University of California, Santa Barbara Library and a leading expert on the Apollo program’s placement of flags on the lunar surface.

“For me, the flag on the moon is an excellent example of something that seems very, very simple, but once you really start thinking about it, you realize is very complex.”

Planting a flag on the moon vs. Earth

With virtually no atmosphere on the moon—and, therefore, no wind—flags that fly freely on Earth would hang like limp cloth in the lunar environment. So engineers had to rethink flagpole design entirely, according to Platoff.

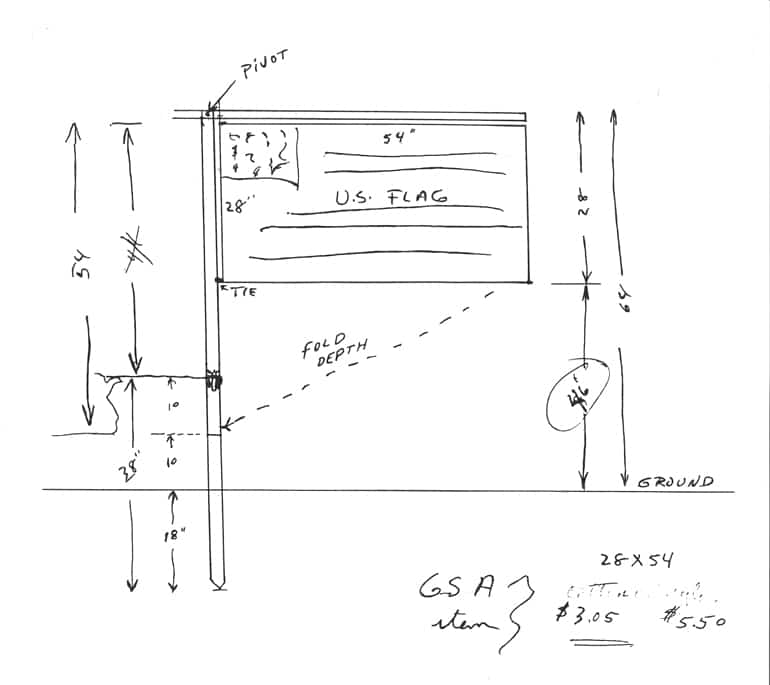

On an earthbound flagpole, the flag is attached at the hoist—the vertical section closest to the pole—at both the top and bottom of the flag. The pole might slide through a sleeve on the hoist side of the flag, or attach by grommets or some other type of fastener. A lunar flag, however, is anchored to the pole only at the bottom. A horizontal crossbar at the top mainly holds it in place.

“A lunar flagpole has three parts,” Platoff explains. “There are two vertical sections, and then the horizontal crossbar that’s hinged at the top of the upper vertical section.”

To deploy the flag, one astronaut used a sampling hammer to pound the lower vertical section into the ground. The other astronaut extended the telescoping crossbar and raised it to a 90-degree angle with the vertical section to click it into place. Then the two astronauts slid the upper part of the pole into the lower one.

“Once they got the flag up, several factors made it look as though it was flying,” Platoff notes. “First there were wrinkles in it because of how tightly it was packed. And these add to the illusion that the flag is waving. Also, the astronauts didn’t always get the horizontal crossbar extended all the way—they were working in pressurized spacesuits and really cumbersome gloves, after all—which caused the flag to bunch up in places. That also made it look like it’s waving.”

Getting the flag to space

Simply getting the flag to the moon also proved a challenge for NASA engineers.

“The Apollo 11 and 12 flags were stored on the ladder of the lunar module,” says Platoff. “It was kind of a last-minute add-on, and I think that’s why they picked that location. But they had to protect it from the engines of the lunar module. As the astronauts were coming down to land, they were firing the engines to slow themselves down. And those engines got really hot. Without adequate thermal protection, the flag would have been gone.”

To protect Old Glory, engineers built a metal shroud that went around the apparatus on the ladder. They also added some insulating blanket material. On later missions, the flag was moved to a storage compartment outside the lunar module.

“It was basically the space where they kept their cameras, hammers, sampling scoops, and other equipment. And that area was already thermally protected,” Platoff says.

What is vexillology?

Though her interest in flags developed at an early age, it wasn’t until Platoff started college that she realized entire books had been written on the subject, or that organizations exist for people who share her passion.

“That was when I also discovered there is a name for it—vexillology. Once I got in touch with this larger community, I was no longer isolated, and I started reading everything I could get my hands on,” Platoff says.

An opportunity of a lifetime came along when Whitney Smith, the father of modern vexillology, and director of the Flag Research Center in Winchester, Massachusetts, invited Platoff to do some research with him in her hometown of Topeka, Kansas. It happened to be close to where a meeting of the North American Vexillological Association (NAVA) was set to take place. “He is the person I really consider to have been my mentor,” Platoff says. Still an active NAVA member, Platoff serves as director of the organization’s digital library.

When Smith invited Platoff to attend the NAVA meeting, her hobby transitioned into a serious scholarly pursuit. Later, her husband took a job at Johnson Space Center in Houston, and a television interview with one of the engineers who designed the lunar flagpole for the Apollo 11 mission piqued her interest in flags on the moon as a research project.

“I’d also always been interested in the space program, so this was the perfect melding of my two interests,” she says.

Source: UC Santa Barbara