Over the next 80 years, a warming planet will cause stronger storm winds, triggering larger and more frequent extreme waves, according to new research.

Researchers simulated Earth’s changing climate under different wind conditions, recreating thousands of simulated storms to evaluate the magnitude and frequency of extreme events.

They find that if we don’t curb global emissions, there will be an increase of up to 10% in the frequency and magnitude of extreme waves in extensive ocean regions.

In contrast, researchers found there would be a significantly lower increase where effective steps are taken to reduce emissions and dependence on fossil fuels. In both scenarios, the largest increase in magnitude and frequency of extreme waves is in the Southern Ocean.

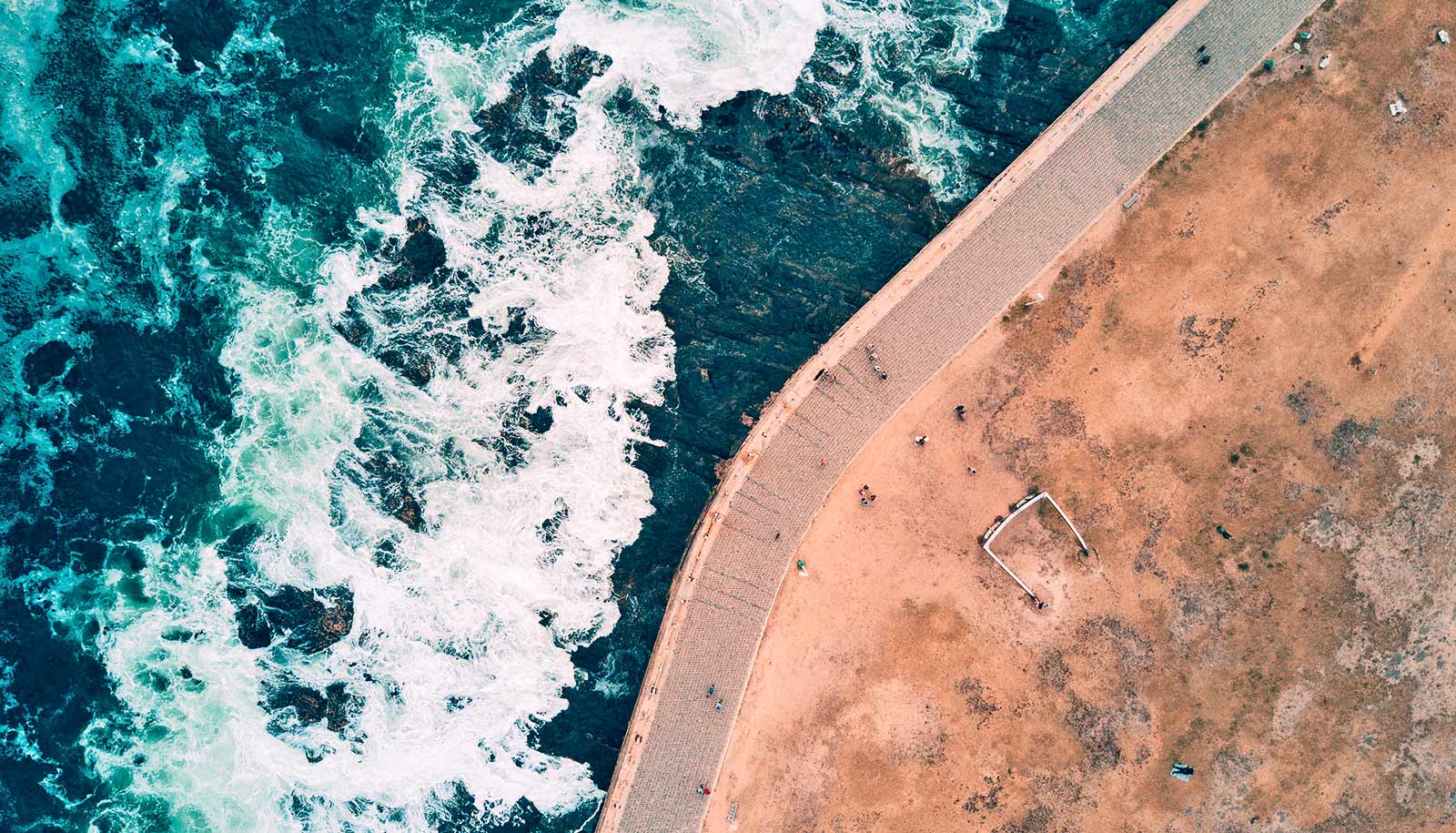

More storms and extreme waves would result in rising sea levels and damage to infrastructure, says Ian Young, a professor and infrastructure engineering researcher at the University of Melbourne.

“Around 290 million people across the world already live in regions where there is a 1% probability of flood every year,” Young says.

“An increase in the risk of extreme wave events may be catastrophic, as larger and more frequent storms will cause more flooding and coastline erosion.”

The study shows that the Southern Ocean region is significantly more prone to extreme wave increases with potential impact to Australian, Pacific, and South American coastlines by the end of 21st century, says lead researcher Alberto Meucci, a postdoctoral fellow in ocean wave modeling.

“The results we have seen present another strong case for reduction of emissions through transition to clean energy if we want to reduce the severity of damage to global coastlines,” Meucci says.

The study appears in Science Advances. Additional researchers from the University of Melbourne, CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere in Hobart, and the IHE-Delft Institute for Water Education in the Netherlands contributed to the work.

Funding for the research came from ARC grants.

Source: University of Melbourne