New evidence suggests a gigantic tsunami hit the California coast 900 years ago, removing three to five times more sand than any El Niño storm in history. The researchers also estimate how far inland the coast eroded.

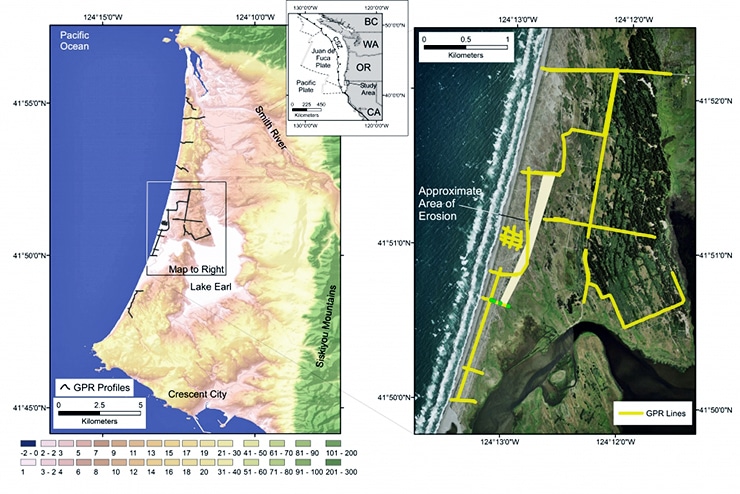

“We found a very distinct signature in the GPR data that indicated a tsunami and confirmed it with independent records detailing a tsunami in the area 900 years ago,” explains lead author Alexander Simms, an associate professor in University of California, Santa Barbara’s earth science department and Earth Research Institute.

“By using GPR, we were able to see a much broader view of the damage caused by that tsunami and measure the amount of sand removed from the beach.”

According to Simms, the magnitude and geography of that epic wave were similar to the one that occurred in Japan in 2011. Geologic records show that these large tsunamis hit the northwestern United States (Northern California through Washington state) every 300 to 500 years. The last one occurred in January 1700, which means another tsunami could happen any time in the next 200 to 300 years.

“People have tried to figure out how far inland these waves hit, but our analysis provides concrete evidence of just how far inland the coast was eroded,” Simms says. “Any structures would not only have been inundated, they would have been eroded away by the tsunami wave.”

When a tsunami recedes from land, it removes sand and reshapes the coastline. In the case of the event 900 years ago, the beach was eroded more than 6 feet down and more than 360 feet inland.

“That’s a big wedge of sand that moved from the beach,” Simms explains. “But because there is so much sand in the system along the coast right after a tsunami, the beach heals pretty quickly on geological timescales. Some of the sand returns from being taken out to sea by the tsunami, but some comes from river catchments that deliver additional sand to the beach as a result of the concomitant earthquake.”

Slow earthquakes could reveal how tsunamis start

While the erosional scar can heal rather quickly, Simms notes, initially the coast is reshaped due to newly formed channels, cuts, and scarps. Once the beach fills in, he adds, the coastline straightens and returns to what it looked like prior to the tsunami. The paper demonstrates this process after the December 26, 2004 Sumatra tsunami, with satellite imagery from before the event, one month after, and four years later.

“The important thing to remember is that these tsunamis can erode the beach up to 360 feet inland,” Simms says. “That means you have to be far inland to be safe when one of them occurs.”

The researchers report their findings in the journal Marine Geology.

Source: UC Santa Barbara