A new study may offer an explanation for cases of epilepsy that currently have no known cause.

Epilepsy is a disorder that disrupts the normal pattern of electrical activity in the brain and often results in seizures. In many cases, the underlying cause is unknown, according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

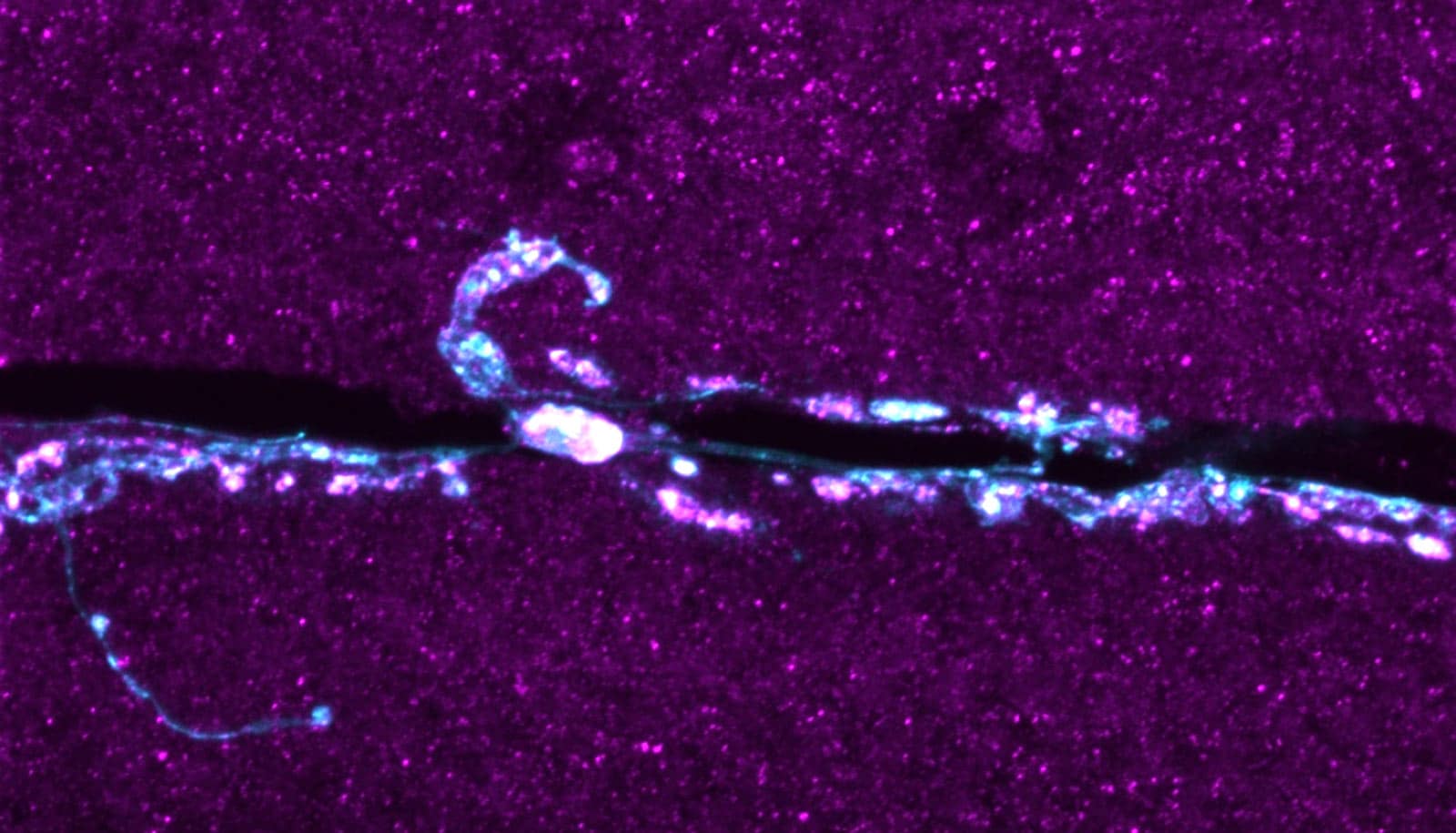

For the study in Molecular Neurobiology, the researchers studied a gene in mice that influences the formation and function of connections between muscle and motor neurons, which control bodily movement.

They discovered that when a protein called TMEM184B, found on cell membranes of neurons, isn’t present, neurons appeared damaged and fired too often, says lead author Tiffany Cho, who was a research technician in the lab of Martha Bhattacharya at the University of Arizona.

The researchers wondered how the seemingly damaged neurons might affect the ability of the neuron to fire the muscles properly. So, Cho and her coauthors next investigated the corresponding protein, called Tmep, in fruit flies, which are easier to study at the cellular level.

“What we found in the fruit flies was that the neurons seem to overreact to an individual stimulus,” says Bhattacharya, an assistant professor in the department of neuroscience and director of the Bhattacharya Lab, which explores early stages of deterioration of brain cell health in neurodegenerative diseases.

This suggests that Tmep—and TMEM184B by extension—are responsible for controlling excitability of neurons.

“This is related to what happens to patients with epilepsy, so we think we may have identified a gene involved in some forms of epilepsy that don’t have another explanation,” Bhattacharya says.

The researchers think that Tmep may alter the behavior of ion channels, which control the amount of calcium in the cell, and therefore the likelihood that the neuron will fire.

“When we saw cellular changes in the fruit flies, it really made us think about whether this was also controlling balance of ions, for example charged particles such as calcium in neurons because that’s a common thing that happens with epilepsy. No one had looked at whether this protein controls ion levels until this paper,” Bhattacharya says.

Bhattacharya has also connected with clinicians who have done gene sequencing of alterations of the TMEM184B protein in humans.

“One of the things we’d like to figure out is if those mutations, especially the ones in which the patients have epilepsy or something related, cause this overexcitability that we see,” Bhattacharya says.

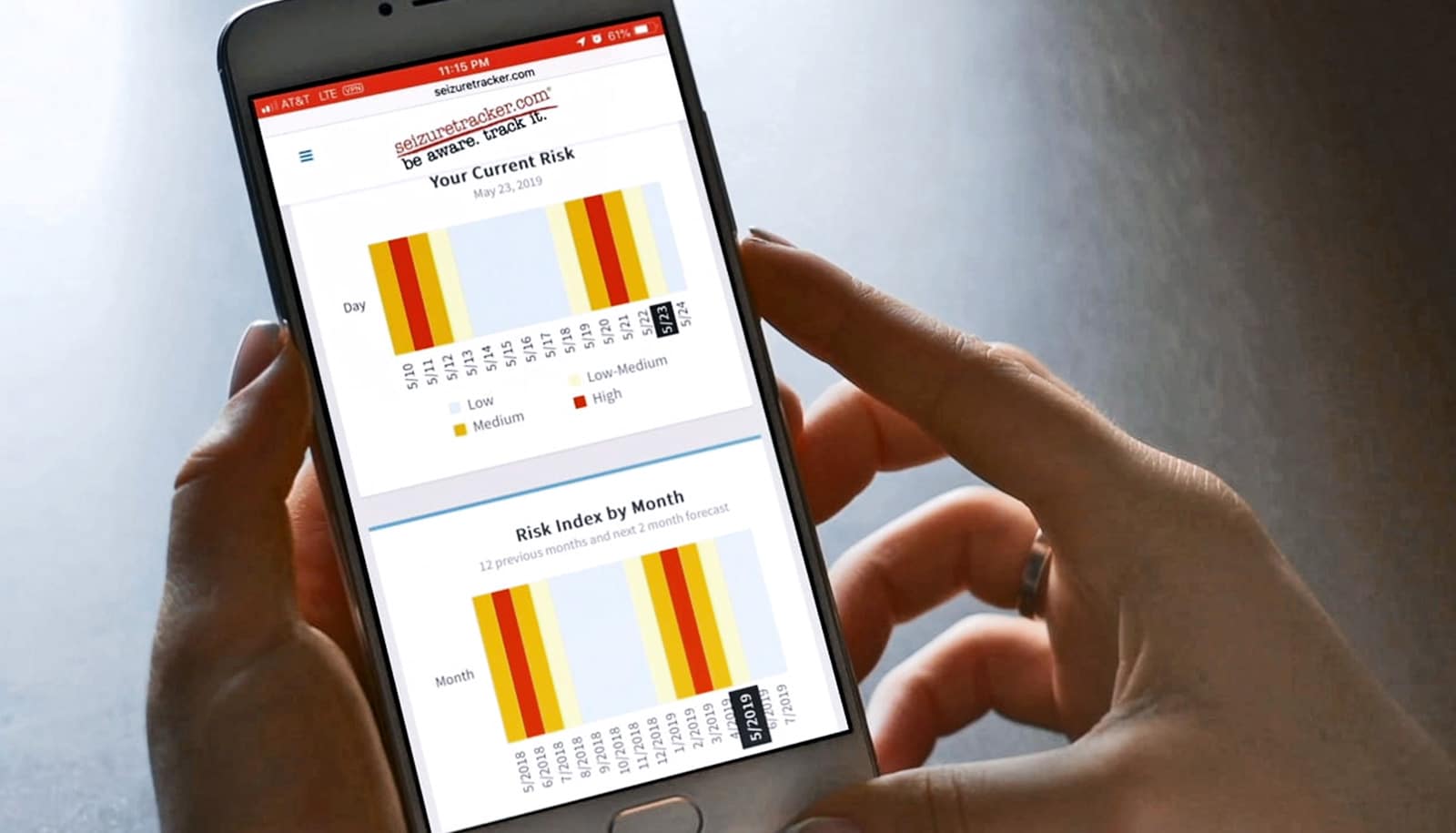

“We can do that in the fruit fly model because we have ways of measuring electrical activity, and that’s something we did in the paper. What we’re trying to do is put those human mutations into the fly genome and see if they cause the same changes in the excitability of the neurons. And if they do that, then we want to know why.”

The researchers also noticed that the fly larvae without Tmep moved much more slowly than other flies when crawling across a plate. As a result, they are curious to see if the protein might also play a role in other neuromuscular diseases—such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS—in addition to disorders like epilepsy.

Source: University of Arizona