As the November 3rd election looms, the nation grapples with fears concerning the safety and integrity of the political process.

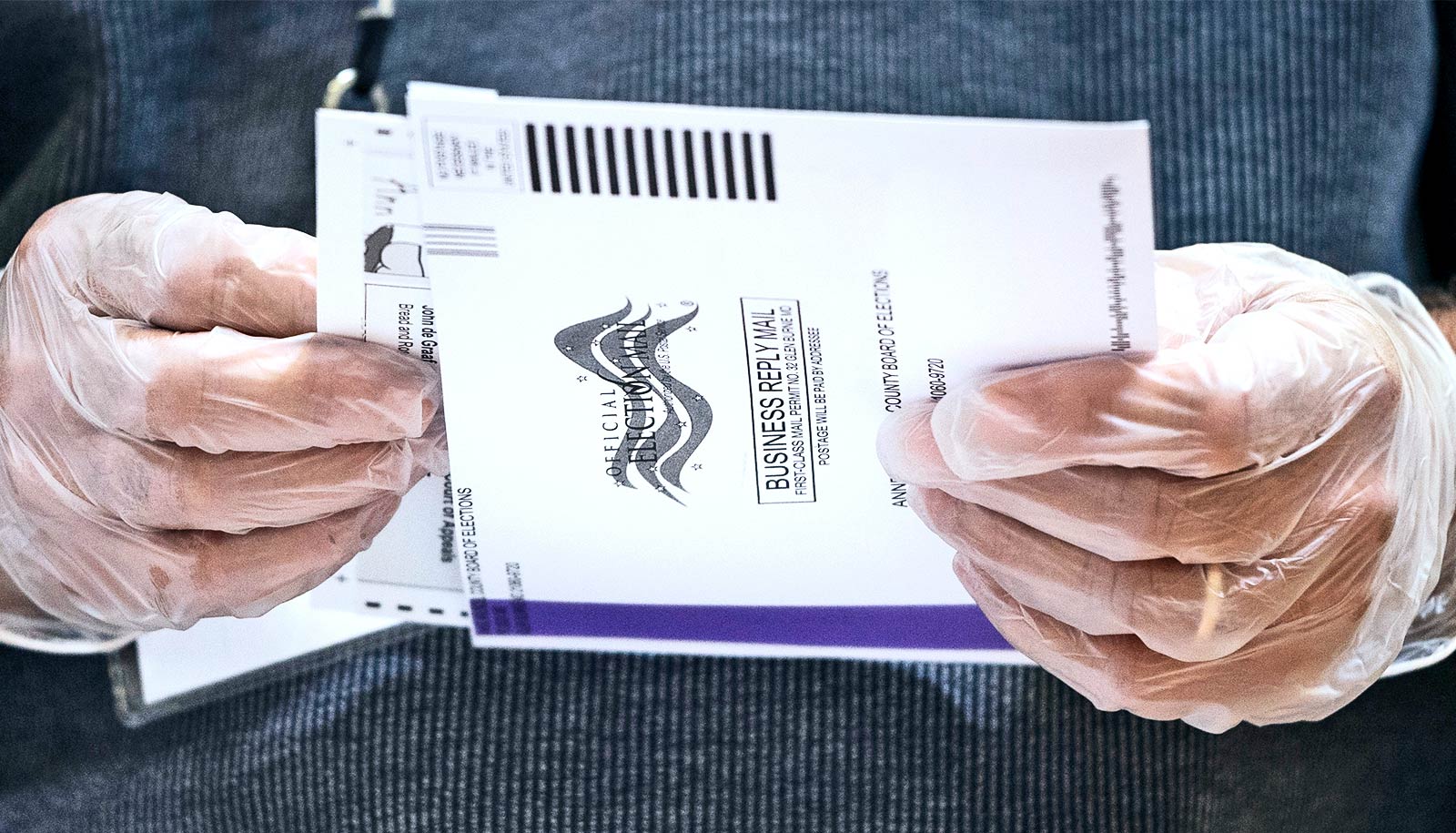

With threats of foreign interference already straining the election, the COVID-19 pandemic introduced newfound uncertainty, prompting large-scale shifts to mail-in voting as a public health measure.

But on the federal, state, and local levels, the effort has descended into a partisan battle. Among the controversies: the US Postal Service—tasked with handling a massive volume of ballots—came under scrutiny for the removal of mail-sorting machines, and a third-party vendor was recently criticized for sending 100,000 Brooklyn residents misnamed absentee ballots.

Mailing issues that could result in a long-term delay of election results increase the likelihood of scenarios that would undermine the process, including candidates claiming premature victory, asserting voter fraud, or even failing to concede a race.

To address these concerns, scholars are providing guidance on the changes needed to increase voter confidence in the fairness and legitimacy of the election.

In April 2020, Richard Pildes, a law professor at New York University and an election analyst for CNN, and others, released a report, “Fair Elections During a Crisis,” which provides recommendations for specific actions that people and organizations that influence perception of the election, including media outlets, tech companies, and legislators should take.

Here, Pildes discusses the current state of Election 2020 and ways to shore up Americans’ eroding faith in democracy:

Is voter mistrust in the election process justified? What are the primary reasons for public concern?

I do not think that significant mistrust is justified. But several short-term and longer-term forces drive this distrust.

At the broadest level, many people on both sides believe this election is existential, in the sense of believing that the country will never be the same if the other side wins. In addition, after the early initial flush of enthusiasm for social media, when it was thought to herald a new, more democratic age, we now are more than aware of how much social media contributes to the toxic nature of our current political culture—a vehicle for spreading misinformation, conspiratorial narratives, and the most sinister account of the actions of public figures and public institutions.

Add to that the fact that we now have candidates who are prepared to tell their supporters the process is rigged against them. There has been a general decline of trust in institutions of all sorts in our populist moment, and the election process has, not surprisingly, been swept up into that.

Moreover, we have indeed become much more aware of genuine problems that do exist with the election process. When we turned a national microscope on the process in the disputed 2000 presidential election, looking at how individual ballots were treated, we saw many problems we had not been aware of before: problems with voting equipment, or inconsistencies in how counties decided what was a valid vote, and other problems. We have made lots of improvements in the technology, the rules, and the process since then, but there’s still a way to go.

Major disagreements exist, as well, over some of the policy issues surrounding voting. In terms of how the election is administered, I understand why people want to keep a careful eye on the process, but I don’t think high levels of distrust are justified. Most election administrators are extremely professional and competent, and they want to ensure the process goes smoothly and properly for voters.

What are the steps state and local governments are taking to ensure a fair and safe election in the wake of COVID-19, and how effective do you think these measures will be?

They have had to fight a two-front war due to COVID-19. On one front, they have had to ramp up preparations for massive increases in the anticipated demand for absentee ballots. This can include hiring staff to process those ballots, which is not simple, and buying new equipment to sort and count these ballots. It also requires communicating new information effectively to voters.

At the same time, they have had to prepare for in-person voting with the public-health measures in place that are needed. This has led to challenges in finding new poll workers to replace traditional poll workers, a high percentage of whom are elderly and might not want to work the polls this year due to their higher risk profile for the virus. It also means many traditional polling sites might not be available, such as those in nursing homes, assisted living facilities, some schools, and some religious institutions.

People might not realize how little time, as a practical matter, has been available to implement these changes. On top of that, states and localities are financially strapped, even more than usual, due to the effects that dealing with the virus has had on their economies. Congress provided about $400 million in funding to help, but that’s not nearly enough to cover all the costs involved. Private funders have started filling some of those gaps, but we do not want to depend on private money to run our elections.

I think it’s inevitable we are going to run into some problems. But election officials have been working heroically around the clock for months now, and I am hopeful any problems, while unfortunate for individual voters, are not going to amount to anything significant in the grand scheme of things.

Which agencies and institutions have the most significant roles to play in protecting the process and restoring trust in election outcomes?

As a result of historical processes set in motion when the Constitution was adopted, we have an extremely decentralized system of running elections, even for national offices.

Election officials at the county level are the key frontline actors; they are responsible for many of the decisions about administering elections, including the accurate counting of the vote. At the next level up, secretaries of states are typically the chief election administrators; they are the ones who implement the state’s laws, including making choices in areas where the law has left them discretion. But these processes take place within the framework of laws the state legislature has enacted, and these laws vary from state to state on matters like how many days of early voting there might be, or when absentee ballots can be requested and when they must be returned. And in the United States, courts have become critical institutions as well, often pulled in to resolve legal disputes. That includes states courts as well as federal courts.

All this makes for a complex system with many critical actors. State legislation is of course key before voting begins, but then the process is primarily in the hands of local and state election administrators. Many of them do a highly professional and competent job, though they do not get the appreciation they deserve—especially this year, when they face unprecedented stresses.

Can voters who are concerned about the integrity of the 2020 election do anything to address their unease?

The single most important thing voters can do, particularly if they live in battleground states, is vote in person. This includes making use of early in-person voting options, which many states have expanded for this election. Voters with exceptional high-health risks have the absentee option, but voters who can vote in person should do that, in my view.

I know that message will sound odd after all the emphasis on expanding opportunities for absentee voting. It’s good that voters have that option, but we know various problems tend to arise with absentee voting, particularly for those voting absentee for the first time.

These ballots are often rejected at high rates, ranging from 4 to 20% in recent primaries. There are concerns about how efficiently the US Postal Service will be able to get ballots delivered back to election officials, if voters send them back by mail—instead of returning them in person, to drop boxes, or election offices.

But even if all that goes smoothly, we want to avoid a situation in which we won’t know the winner of the election until many days after November 3. A large volume of absentee ballots that cannot be counted until several days after the election presents one of the greatest risks, in our current political culture, of tremendous turmoil.

Voting in person is reasonably safe, as public-health experts have assured us, given the measures that will be in place. This might vary some from place to place, depending on rates of infection. But voting in person is the best thing most voters can do to protect the health of American democracy this fall.

What happens if the outcome of the election is still unclear by January?

If we reach that point, we are in a dangerous situation. The Electoral College is currently scheduled to vote on December 14—legislation is required to change that date, which Senator Marco Rubio has proposed and I’ve endorsed.

At this point, it seems unlikely that date will get pushed back, even if states would be better off this year having more time if they need it to complete their vote-counting processes. If we do not know the outcome by January, that would have to be because some major dispute existed about how the election was conducted in one or more decisive states and who had validly won that state or states.

The next two dates on the calendar are January 3, when the Constitution requires that the newly elected Congress take over, and January 6, when that Congress receives and “counts” the electoral votes. In deciding which votes count, Congress would begin the process of resolving a dispute, if it still existed, about who had won key states.

The final date is January 20, when the Constitution terminates the incumbent President’s term. In the most intensely disputed presidential election in our history, the 1876 election, the dispute was not resolved until two days before inauguration day—and back then, that was in March, not January—so the dispute went on for four months.

And if the election is not resolved by January 20, the new Speaker of the House would become “Acting President” until the process of selecting the new President had been completed.

Source: New York University