The Earth of 3.2 billion years ago was a “water world” of submerged continents, according to new research.

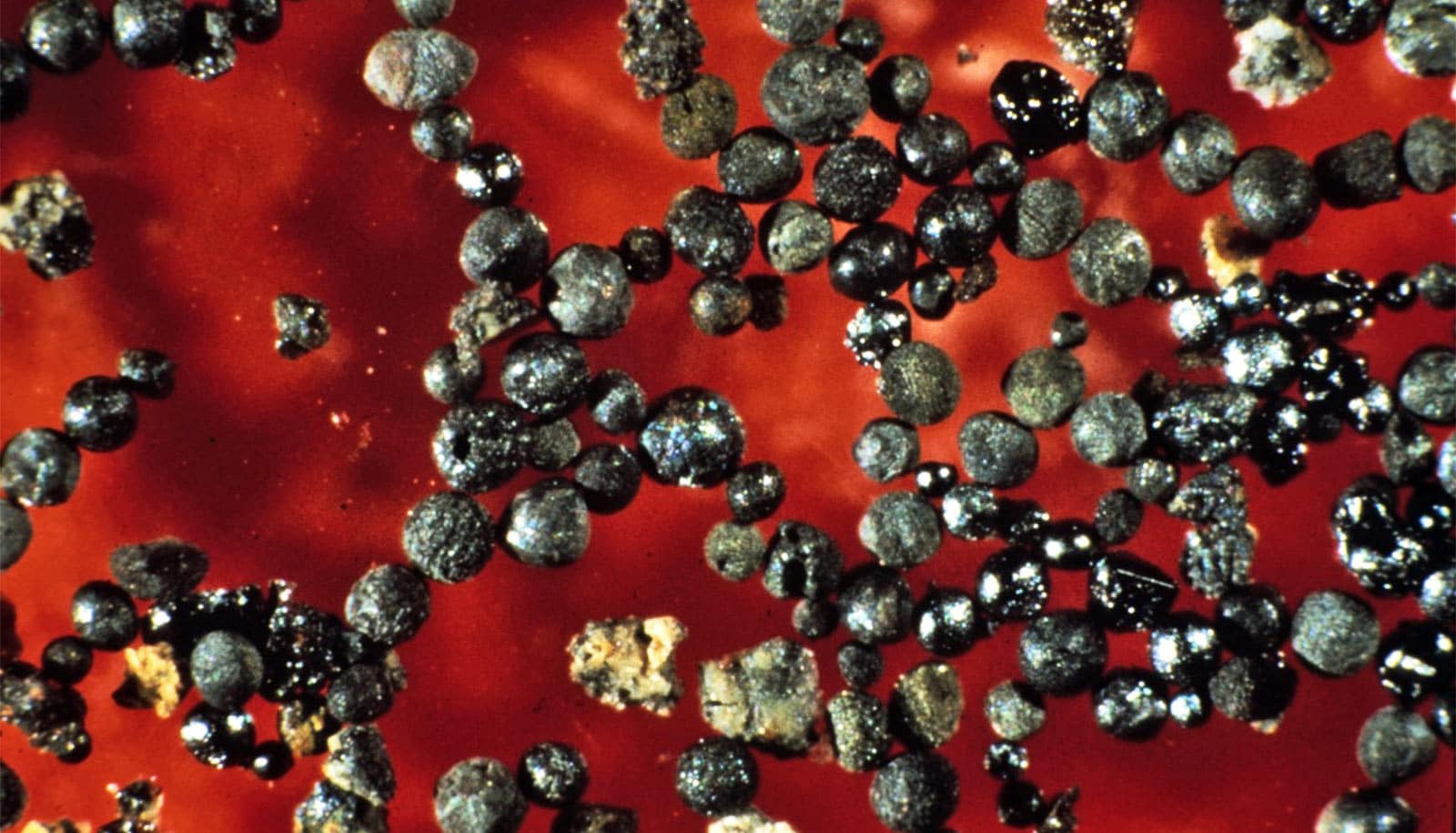

Researchers analyzed oxygen isotope data from ancient ocean crust now exposed on land in Australia to make their discovery.

“The 3.2-billion-year-old section of ocean crust we studied looks exactly like much, much younger ocean crust.”

The finding could have major implications for the origin of life, the researchers report.

“An early Earth without emergent continents may have resembled a ‘water world,’ providing an important environmental constraint on the origin and evolution of life on Earth as well as its possible existence elsewhere,” the researchers write in a paper in Nature Geoscience.

The long-gone oceans of early Earth

Work on the project started when the researchers began talking at conferences and learned about the well-preserved, 3.2-billion-year-old ocean crust from the Archaean eon (4 billion to 2.5 billion years ago) in a remote part of the state of Western Australia. Previous studies meant there was already a big library of geochemical data from the site.

Benjamin Johnson, an assistant professor of geological and atmospheric sciences at Iowa State University and a recent postdoctoral research associate at the University of Colorado Boulder, joined Boswell Wing, an associate professor of geological sciences at Colorado, and his research group and went to see the ocean crust for himself. The 2018 trip involved a flight to Perth and a 17-hour drive north to the coastal region near Port Hedland.

After taking his own rock samples and digging into the library of existing data, Johnson created a cross-section grid of the oxygen isotope and temperature values found in the rock.

Isotopes are atoms of a chemical element with the same number of protons within the nucleus, but differing numbers of neutrons. In this case, differences in oxygen isotopes preserved with the ancient rock provide clues about the interaction of rock and water billions of years ago.

Once he had two-dimensional grids based on whole-rock data, Johnson created an inverse model to come up with estimates of the oxygen isotopes within the ancient oceans. The result: Ancient seawater was enriched with about 4 parts per thousand more of a heavy isotope of oxygen (oxygen with eight protons and 10 neutrons, written as 18O) than an ice-free ocean of today.

Two theories

How to explain that decrease in heavy isotopes over time?

The researchers suggest two possible ways: Water cycling through the ancient ocean crust was different than today’s seawater with a lot more high-temperature interactions that could have enriched the ocean with the heavy isotopes of oxygen. Or, water cycling from continental rock could have reduced the percentage of heavy isotopes in ocean water.

“Our preferred hypothesis—and in some ways the simplest—is that continental weathering from land began sometime after 3.2 billion years ago and began to draw down the amount of heavy isotopes in the ocean,” Johnson says.

The idea that water cycling through ocean crust in a way distinct from how it happens today, causing the difference in isotope composition “is not supported by the rocks,” Johnson says.

“The 3.2-billion-year-old section of ocean crust we studied looks exactly like much, much younger ocean crust,” he explains.

The study demonstrates that geologists can build models and find new, quantitative ways to solve a problem—even when that problem involves seawater from 3.2 billion years ago that they’ll never see or sample, Johnson says.

And, Johnson says these models inform us about the environment where life originated and evolved: “Without continents and land above sea level, the only place for the very first ecosystems to evolve would have been in the ocean.”

Grants from the National Science Foundation supported the study and a Lewis and Clark Grant from the American Philosophical Society supported Johnson’s fieldwork in Australia.

Source: Iowa State University