New research raises a question straight out of science fiction: Is it possible to activate the biological impulse that prompts dormancy in some living creatures in others, such as humans?

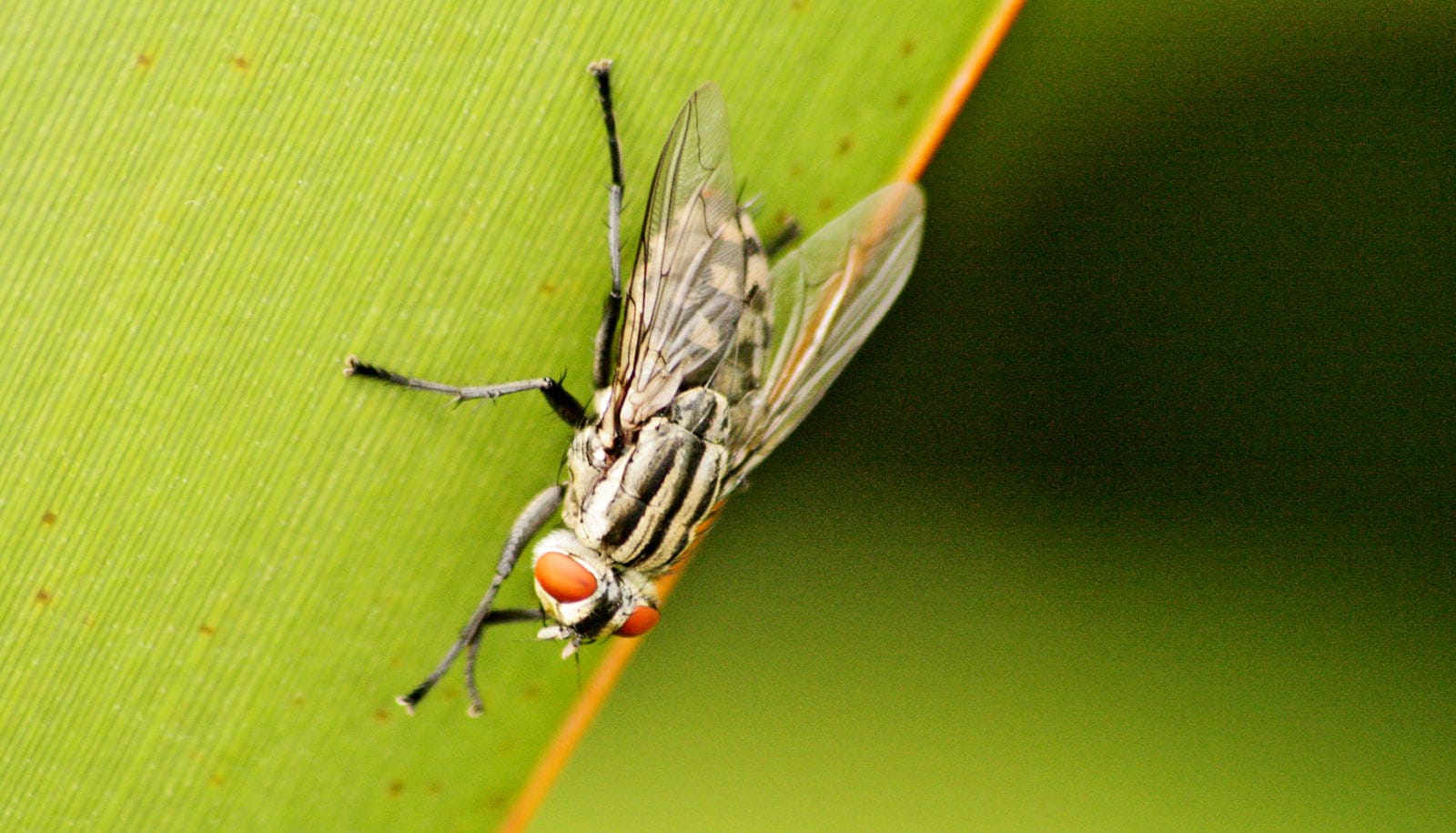

A new study models what regulates metabolism in an insect called the flesh fly during its dormant, or diapause, phase. The flies enter into a state of massive “metabolic depression” that is regularly punctuated with “periodic metabolic arousal,” following a pattern that some mammalian hibernators share.

“This study gives us greater fundamental understanding of how dormancy is regulated,” says study coauthor Dan Hahn, an entomology professor at the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

“Nobody exactly knows what regulates these periodic wakings and entering back into metabolic depression in mammalian hibernators. One of the things that’s special about our study is that we’ve identified one of the regulatory mechanisms for the switch between metabolic depression and periodic arousal in the flesh fly. We want to understand what regulates dormancy and arousal from dormancy for all of the possible downstream applications.”

For the field of entomology, Hahn offers an example of what could be possible if dormancy could be induced or broken in insects whenever needed.

“If you could produce biocontrol insects, such as parasitoid wasps, at a steady rate and store them in dormancy until you need them, it could be a major economic benefit and a major advance for biological control,” says Hahn.

A species that may be key to investigating these ideas is Drosophila melanogaster, the common fruit fly.

“One of our larger goals is to test whether we could induce deep dormancy in different stages of the fruit fly lifecycle as a proof of concept for what we learned about pupal diapause in the flesh fly. These two species are more than 90 million years diverged from one another,” Hahn explains. “So if we can make it work there, how could it be translated to vertebrate cells?”

Hahn says known mammal hibernator species like the ground squirrel may share the same triggers as flesh flies to enter periods of dormancy and periodic arousal, but further research is needed.

“I encourage my colleagues who study mammalian hibernators to explore whether periodic arousal could be regulated the same way in their systems,” he says. “The reason we think mammals could regulate their dormancy-periodic arousal cycles similarly is that all the pieces that are being regulated in these insect cells are regulated in everybody’s cells, if you look at the fundamental cellular biochemistry.”

While applications for this work are still far off, in Hahn’s view this line of basic research could lead to the possibility of inducing and breaking dormancy at will in a wide range of organisms, from improving breeding programs for endangered butterflies to inducing dormancy in human organs to extend the time for transplant, or amputated limbs being kept viable long enough for reattachment.

“These are the things that I dream about—how can we improve society somehow with this science,” Hahn says. “The building blocks that we’re putting forward today could lead to those sorts of advancements.”

The study appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Coauthors are from the University of Florida and Ohio State University.

Source: University of Florida