The field of ecology needs to account for the historical legacy of colonialism that has shaped people and the natural world, researchers argue.

They make this claim about ecology, the field of biology devoted to the study of organisms and their natural environments, in a new perspective in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

To make ecology more inclusive of the world’s diverse people and cultures living in diverse ecosystems, the researchers propose five strategies to untangle the impacts of colonialism on research and thinking in the field today.

“There are significant biases in our understanding of ecology and ecosystems because of this colonial framework of thinking,” says coauthor Madhusudan Katti, associate professor for leadership in public science, and forestry and environmental resources at North Carolina State University.

“We are challenging ecologists to understand and address the legacies of colonialism, and to start engaging in an active process of ‘decolonizing science.'”

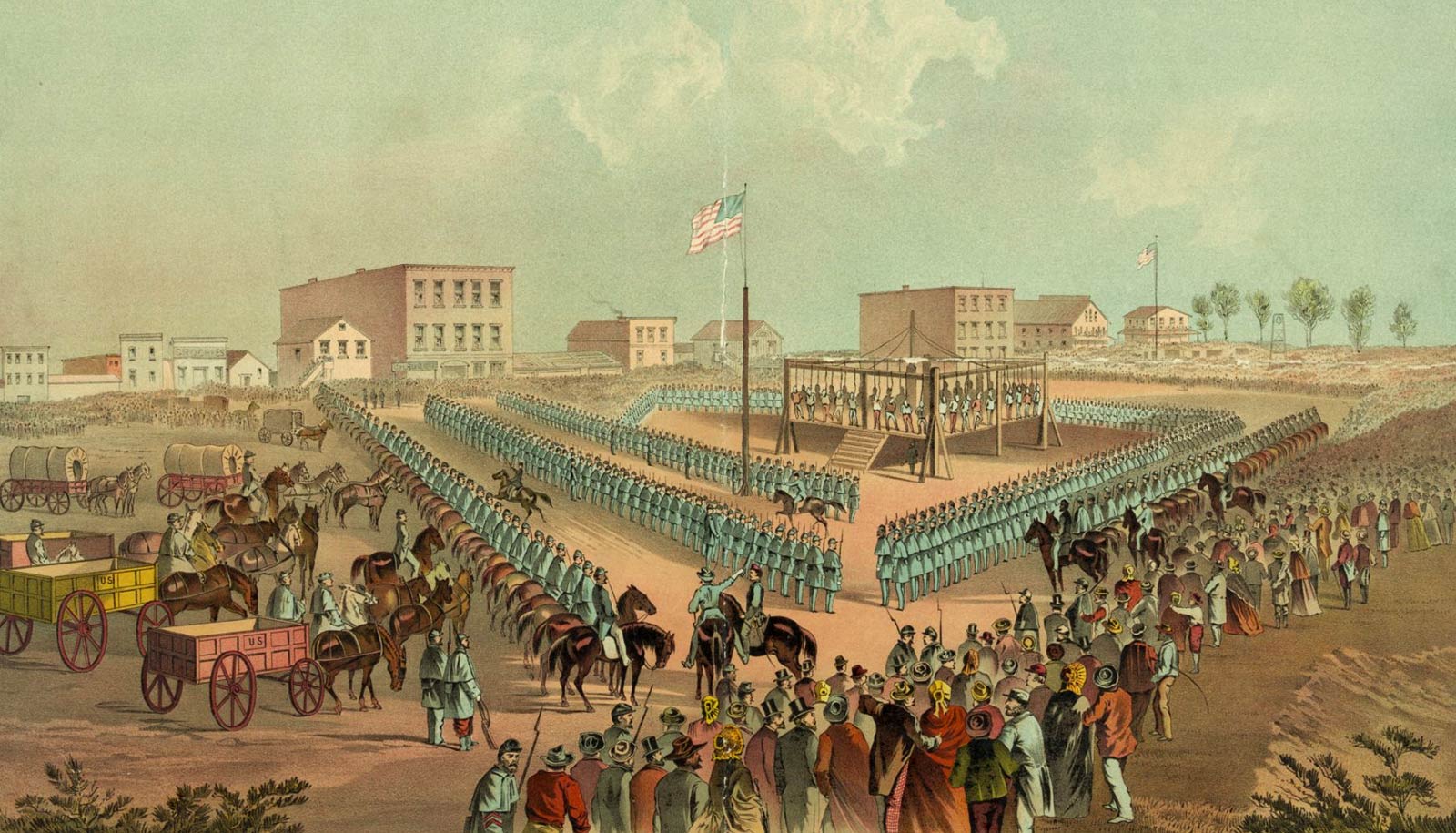

The researchers describe emerging research documenting impacts of European colonialism—the migration, settlement, and exploitation of the Americas, Africa, Asia, and other parts of the world by people from Europe—on people and the natural world, and on ecology.

Examples of how ecological research reflects the impact of colonialism include patterns of vegetation in cities that reflect patterns of racial segregation and discrimination, or in the use of names of prominent European scientists or their patrons in the scientific names for bird species and other organisms rather than names used by Indigenous people, says Katti.

“Indigenous names are often based on observations of behavior or ecology, or represent cultural significance of species, but that traditional ecological knowledge is lost when names are changed,” Katti says. “This is bad for both the colonized people and the science of ecology itself.”

The researchers challenge the field to address colonial legacies using five strategies:

-

- Decolonize the mind. The researchers say this means understanding other knowledge systems from colonized cultures.

- Know your history. That is, understand the history of colonialism in influencing Western ecology, and its role in promoting oppression of other people and in shaping the environment. “Ecology is about organisms living in their ecosystems – that’s what we study,” Katti says. “If you want to study ecology, that includes people. To understand how people shape ecosystems, we have to understand how political power works. Western ecologists have to acknowledge how science has been aligned with colonial power, and how it has been used to perpetuate systems of oppression that continue to this day.”

- Decolonize information. They suggest this should be done by increasing access to academic information, and understanding power dynamics in the ownership and dissemination of data

- Decolonize expertise. Recognize more diverse voices in the field of ecology.

- Establish diverse and inclusive teams to help overcome biases in future research. “The world is enriched by diverse perspectives,” Katti says. “We need scientific teams where everybody is equally empowered to set a robust research agenda and ensure more robust testing of these ideas. If the person with a different hypothesis is not in the room, then you’re never challenged to test and prove their hypothesis, and you’re subject to your own bias.”

Coauthors of the perspective are from the University of Cape Town and North West University in South Africa. Funding came from the National Socio Environmental Synthesis Center under funding received from the National Science Foundation and FLAIR fellowship program—a partnership between the African Academy of Sciences and Royal Society, funded by the UK Government’s Global Challenges Research Fund.

Source: NC State