When the federal government ran up debt between 1776 and 1939, mainly to fund wars, Congress moved swiftly afterwards to repay the loans, a new paper shows.

As a result of the costs of the War of 1812, the debt limit rose to roughly $190 million by 1820. Some 15 years later, the debt was almost entirely gone.

By now, it’s a familiar pattern. America’s national debt rises and Congress increases the debt limit so the government can repay its lenders. Despite the bitter struggles and threats of government shutdown in Congress, this has pretty much been happening since the 1950s.

Today, the debt ceiling stands at $20 trillion with another $10 trillion in debt limit hikes expected over the next decade.

It’s hard to imagine, but there was a time when our government repaid its debt in a timely fashion.

In a paper in PNAS, George J. Hall, professor of economics at Brandeis University, and his New York University colleague Thomas J. Sargent calculated the US debt limit for every year between 1776 and 1939, and found that Congress used to promptly repay the nation’s loans.

How it used to be

For example, as a result of the costs of waging the War of 1812, the debt limit rose to roughly $190 million by 1820. Some 15 years later, the debt was almost entirely gone. By the end of the Civil War, the debt limit was close to $4 billion. It was close to $1 billion by 1890.

The paper did not analyze the reasons for this fiscal responsibility, but Hall says it was likely due to the system back then for issuing bonds.

When the republic was founded, Congress was put in charge of administering US securities. The legislature set the bond’s amount, rate of interest, term to maturity, and tax exemptions.

They did this on a per project basis. For example, Congress issued three Panama Canal bonds to pay for the construction of the canal, and 10 War of 1812 bonds to fund that war. The money was only used for its designated purpose.

For better or worse, there’s probably no going back to the pre-1939 system.

“Congress would design each bond and tell the Treasury you can only use it to pay for this project,” Hall says. “You can’t use it for anything else.”

In most cases, bonds were non-renewable. Once a bond was paid off, Congress needed to design and issue another bond. More often than not, Hall says, Congress chose to lower spending or raise taxes rather than go into debt again.

An understanding that had been in effect since Thomas Jefferson’s presidency guided politicians at that time. The federal government would not spend more than the amount it raised in revenues unless there was a unique set of circumstances or objectives.

“It was basically a policy where permanent expenditures were covered by taxes, and unexpected temporary expenses would be covered by debt,” Hall says.

This system acted as an impediment to spending in excess of tax revenue. The only way to cover excess costs was to gather enough votes to create a new bond, which took time, effort and a lot of horse-trading.

The new way

There was no official debt limit during this period, which is why Hall and Sargent had to calculate the number by aggregating the data on each individual bond issued in every year. Technically speaking, the figure they came up with for each separate year is called an “implied debt limit.”

Bad feelings, not ideas, divide the U.S. Congress

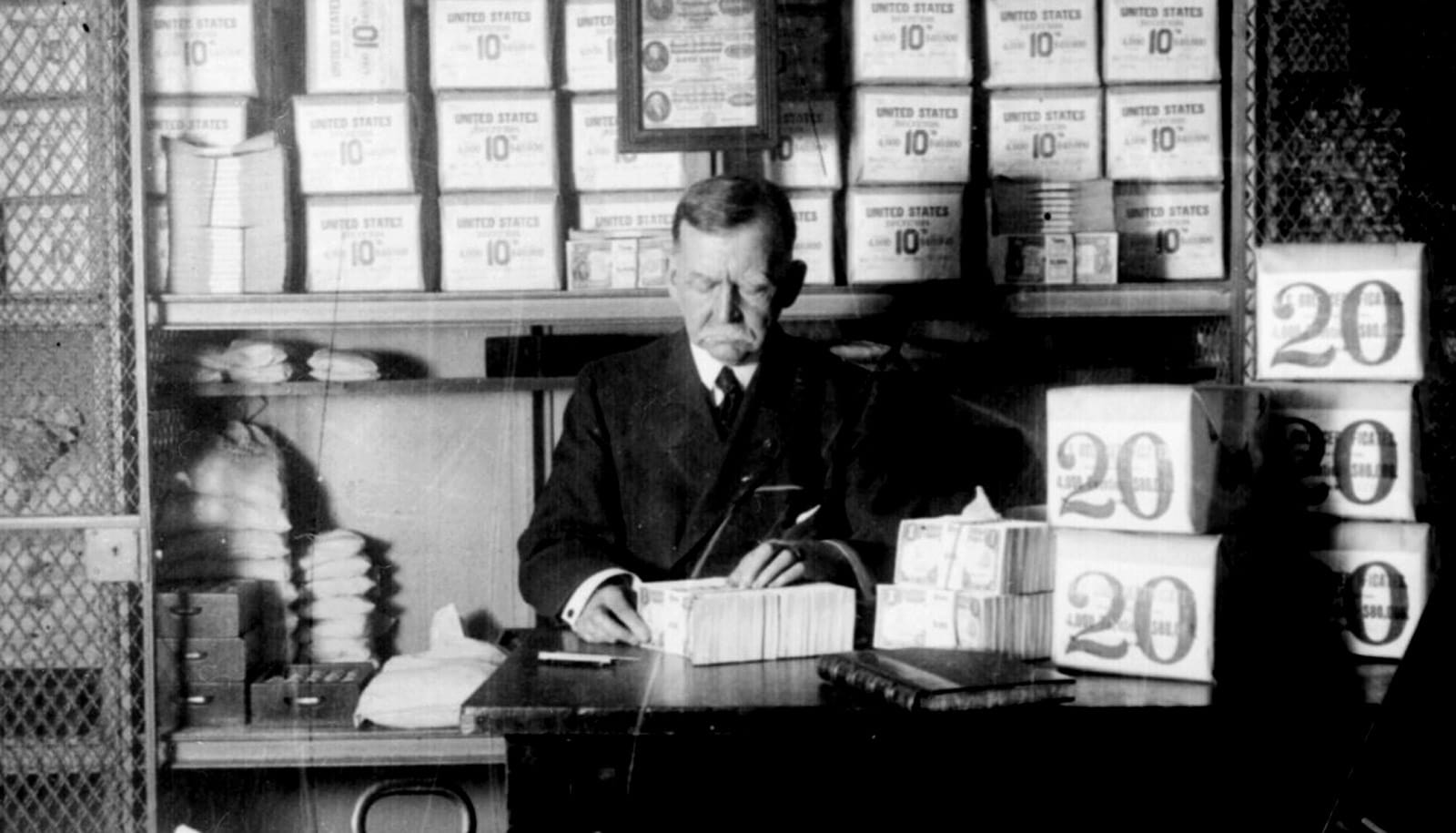

The states still use this approach, authorizing bonds only when needed for a specific program or project. But in the 1920s, the federal government implemented a radically different method. At the request of US Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon, the executive branch took over responsibility for handling securities. The government had racked up significant debt during World War I and Mellon wanted greater flexibility and authority to repay it.

Under the new system, Congress approved a budget and the Treasury Secretary decided how to fund it. He determined how many bonds to issue and set their value. (There has never been a female Treasury Secretary.)

America benefited hugely from the new process. Mellon standardized US bills, notes, and bonds. Freed from the vagaries of the legislative process, US securities became a highly liquid investment, backed by the full faith and credit of the federal government.

“Instead of this weird idiosyncratic collection of bonds that pay for different things from different revenue streams, you have this small set of uniform securities,” says Hall.

But it also meant Congress could pass a budget, then leave it up to the Treasury to worry how to best handle the debt. To some extent, it was like Congress got the credit card but the executive branch had to deal with the bill.

Post-9/11 U.S. war costs will soon top $5.6 trillion

“When Congress authorizes new spending,” Hall says, “it doesn’t have to explain how it’s going to finance it.”

For better or worse, there’s probably no going back to the pre-1939 system. The reliability of US securities provides dependability for the world’s financial markets. Any significant change in our bond-issuing system would have a huge global impact.

Still, there was a principle at work before 1939 that Hall believes is worth keeping in mind. “The basic idea” he says, “is that there should be a much tighter connection between spending and taxation.”

Source: Brandeis University