For patients with a rare lymphoma cancer, aggressive treatment with antibiotics can inhibit both cancer cells and the staphylococcal infections that many develop, researchers report.

A new study shows that the treatment reduces the number of cancer cells and significantly diminishes the cancer for a period of time in patients with severe skin inflammation.

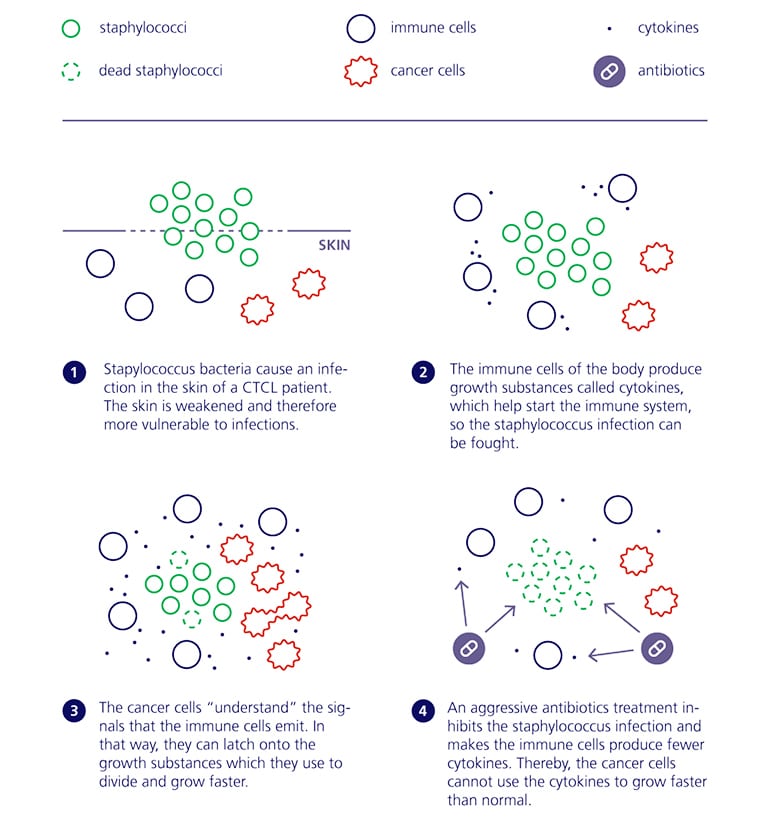

CTCL is a rare lymphoma cancer in the T-cells of the immune system that shows in the skin. Many patients contract staphylococcal infections in the skin. The cancer weakens the patient’s immune system and makes the skin less resistant to bacteria.

During a staphylococcal infection, the healthy immune cells in the body work at full throttle. They produce growth substances called cytokines, which get the immune system up and running. The cancer cells latch onto the growth substances, using them to accelerate their own growth. The research results show for the first time that the antibiotic treatment can slow down this process.

Cutting off the fuel

“When we inhibit the staphylococcal bacteria with antibiotics, we simultaneously remove the activation of the immune cells. This means that they do not produce as many cytokines, and therefore the cancer cells cannot get the extra ‘fuel’. As a result, the cancer cells are inhibited from growing as fast as they did during the bacterial attack. This finding is ground-breaking as it is the first time ever that we see this connection between bacteria and cancer cells in patients,” says Niels Ødum, a professor in the LEO Foundation Skin Immunology Research Center at the University of Copenhagen.

The finding is the result of many years of research, the researchers conducting molecular studies and laboratory tests, taking tissue samples from skin and blood, and conducting clinical studies of carefully selected patients.

So far, CTCL patients with infections in the skin have only reluctantly been given antibiotics because it was feared that the infection would come back as antibiotic-resistant staphylococci after the treatment. The researchers behind the finding believe that the new results will change this.

“It has previously been seen that antibiotics have had some kind of positive effect on some of these patients, but it has never been studied what it actually does to the cancer itself. Our finding shows that it may actually be a good idea to give patients with staphylococci on the skin this treatment because it inhibits the cancer and at the same time possibly reduces the risk of new infections,” says Ødum.

Will it work for cancers besides CTCL?

It is still difficult to say whether the new knowledge can trasfer to other types of cancer. For the researchers, the next step is to initially look more closely at the link between cancer and bacteria.

“We do not know if this finding is only valid for lymphoma. We see it particularly in this type of cancer because it is a cancer within the immune system. The cancer cells already ‘understand’ the signals that the immune cells send out. When the immune cells are put to work, so are the cancer cells. At any rate, it is very interesting and relevant to take a closer look at the interaction between bacteria and cancer, which we see here,” says Ødum.

“The next step will be the development of new treatments that only target the ‘bad’ bacteria, without harming the ‘good’ bacteria, which protects the skin,” he says.

The study appears in the journal Blood.

Additional researchers are from Aarhus and Zealand University Hospitals, Aarhus University, and Bispebjerg University Hospitals. Support for the study came from the LEO Foundation, the Novo Nordisk Foundation, the Independent Research Fund Denmark, the Lundbeck Foundation, the Danish Cancer Society, and TV2.

Source: University of Copenhagen