Crop rotation and diversification can help combat the western corn rootworm’s resistance to biotech crops, research confirms.

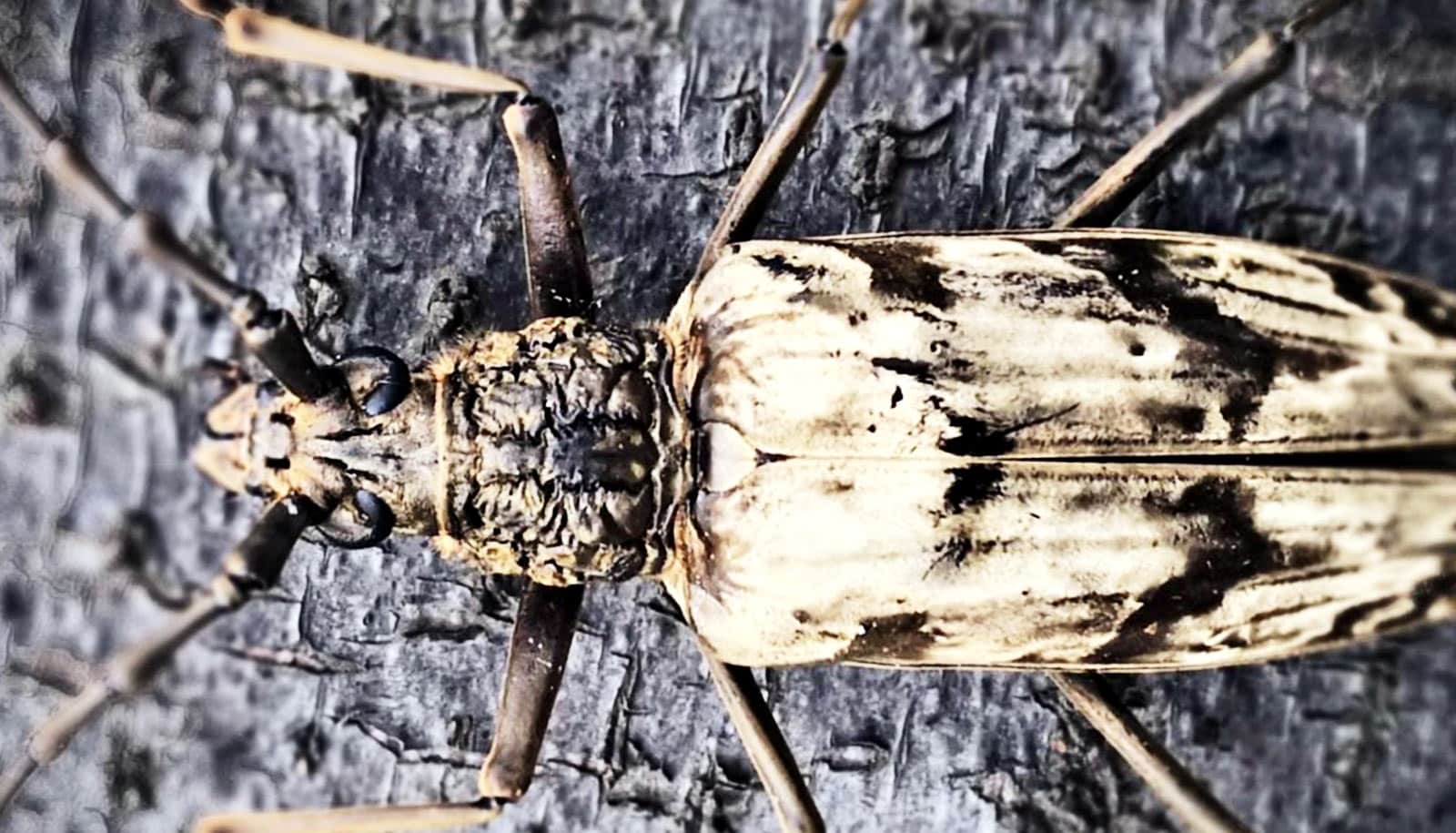

Nicknamed the “billion-dollar beetle” for its enormous economic costs to growers in the United States each year, the western corn rootworm is one of the most devastating pests farmers face.

“They are quite insidious. They’re in the soil, gnawing away at the roots and cutting off the terminal ends of the roots—the lifeblood of corn,” says Bruce Tabashnik, professor and head of the University of Arizona entomology department. “And if they’re damaging enough, the corn plants actually fall over.”

Genetically modified crops have been an important tool in the battle against pests such as these, increasing yields while reducing farmers’ reliance on broad-spectrum insecticides that can be harmful to people and the environment.

Corn was genetically engineered to produce proteins from the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis, or Bt, that kill rootworm larvae but are not toxic to humans or wildlife. The technology was introduced in 2003 and has helped keep the corn rootworm at bay, but the pest has begun to evolve resistance.

“So, now the efficacy of this technology is threatened, and if farmers were to lose Bt corn, the western corn rootworm would become a billion-dollar pest again,” says Yves Carrière, a professor of entomology in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Carrière is lead author of a study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that evaluates the effectiveness of crop rotation in mitigating the damage caused by resistant corn rootworms.

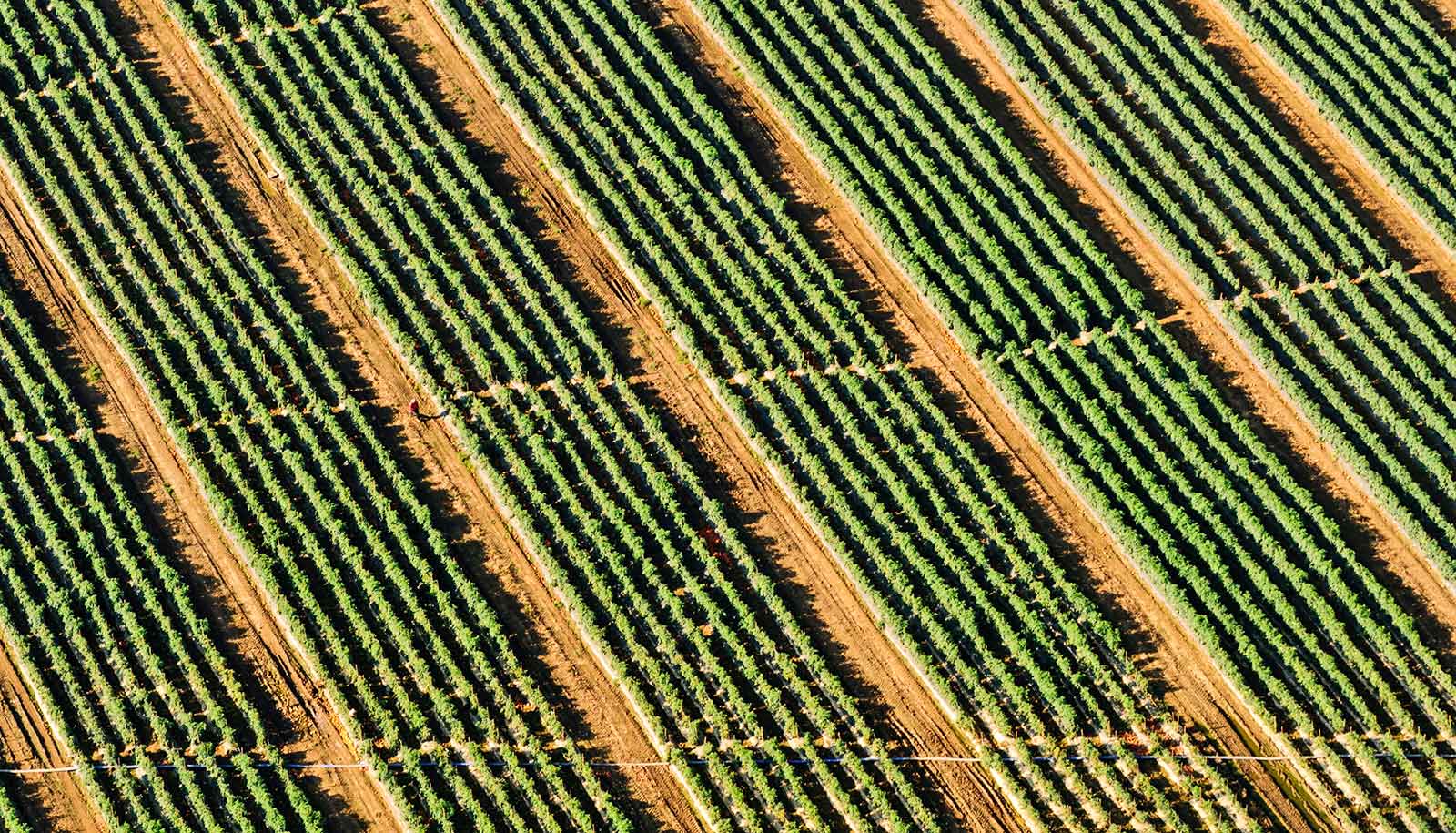

Crop rotation, the practice of growing different crops in the same field across seasons, has long been used for pest control. In 2016, the Environmental Protection Agency mandated crop rotation as a primary means of reducing the damage to Bt corn fields caused by resistant corn rootworms, but there have been limited scientific studies to support the efficacy of this tactic.

Carrière and his team rigorously tested this approach by analyzing six years of field data from 25 crop reporting districts in Illinois, Iowa, and Minnesota—three states facing some of the most severe rootworm damage to Bt cornfields.

The results show that rotation works. By cycling different types of Bt corn and rotating corn with other crops, farmers greatly reduced rootworm damage.

Most notably, crop rotation was effective even in areas of Illinois and Iowa where rootworm resistance to corn and soybean rotation had been previously reported.

According to the study, crop rotation provides several other benefits as well, including increased yield, reductions in fertilizer use, and better pest control across the board.

“Farmers have to diversify their Bt crops and rotate,” Carrière says. “Diversify the landscape and the use of pest control methods. No one technology is the silver bullet.”

In many ways, the study reaffirms traditional agricultural knowledge.

“People have been rotating crops since the dawn of farming. The new agricultural technology we develop can only be sustained if we put it in the context of things we’ve known for thousands of years,” Tabashnik says. “If we just put it out there and forget what we’ve learned in terms of rotating crops, it won’t last.”

The authors emphasize that increasing crop rotation is essential for sustaining the economic and environmental benefits provided by rootworm-active Bt corn. During the six years of the study, the average percentage of corn rotated to other crops per state ranged from about 55 to 75%.

“This is one of the most important applications of Bt crops in the United States,” Carrière says. “If we lose this technology and we start using soil insecticides again, it’s going to have a big negative environmental impact.”

Tabashnik and colleagues from North Carolina State University, the University of California, Davis, McGill University, and Stockholm University are coauthors of the study.

Source: University of Arizona