People in prison and correctional officers have an elevated risk during pandemics, especially ones that stem from a highly infectious agent like COVID-19, researchers say.

Because people in prisons and jails live in such close quarters, enforcing social distancing practices that health officials recommend to limit the virus spread isn’t feasible.

“When people are incarcerated in dormitory style situations, or in cells with multiple people—and then you add in the logistics of making sure inmates get fed and their other basic needs are met—there’s no distancing that can go on for any extended period of time,” says Daniel Nagin, professor of statistics and public policy in Carnegie Mellon University’s Heinz College of Information Systems and Public Policy.

“Once this virus gets introduced into that kind of environment, it will inevitably spread, and then it can’t be controlled. The only way to stop that from happening is for the virus to not be introduced in the first place.”

“A prison in a pandemic becomes akin to a cruise ship—people are crowded into a shared space that they cannot leave.”

That reality is leading many jurisdictions in the United States to take the unprecedented step of releasing large numbers of inmates to prevent coronavirus outbreaks. Nagin says he believes the decision to release inmates has merit, but isn’t without complications in practice.

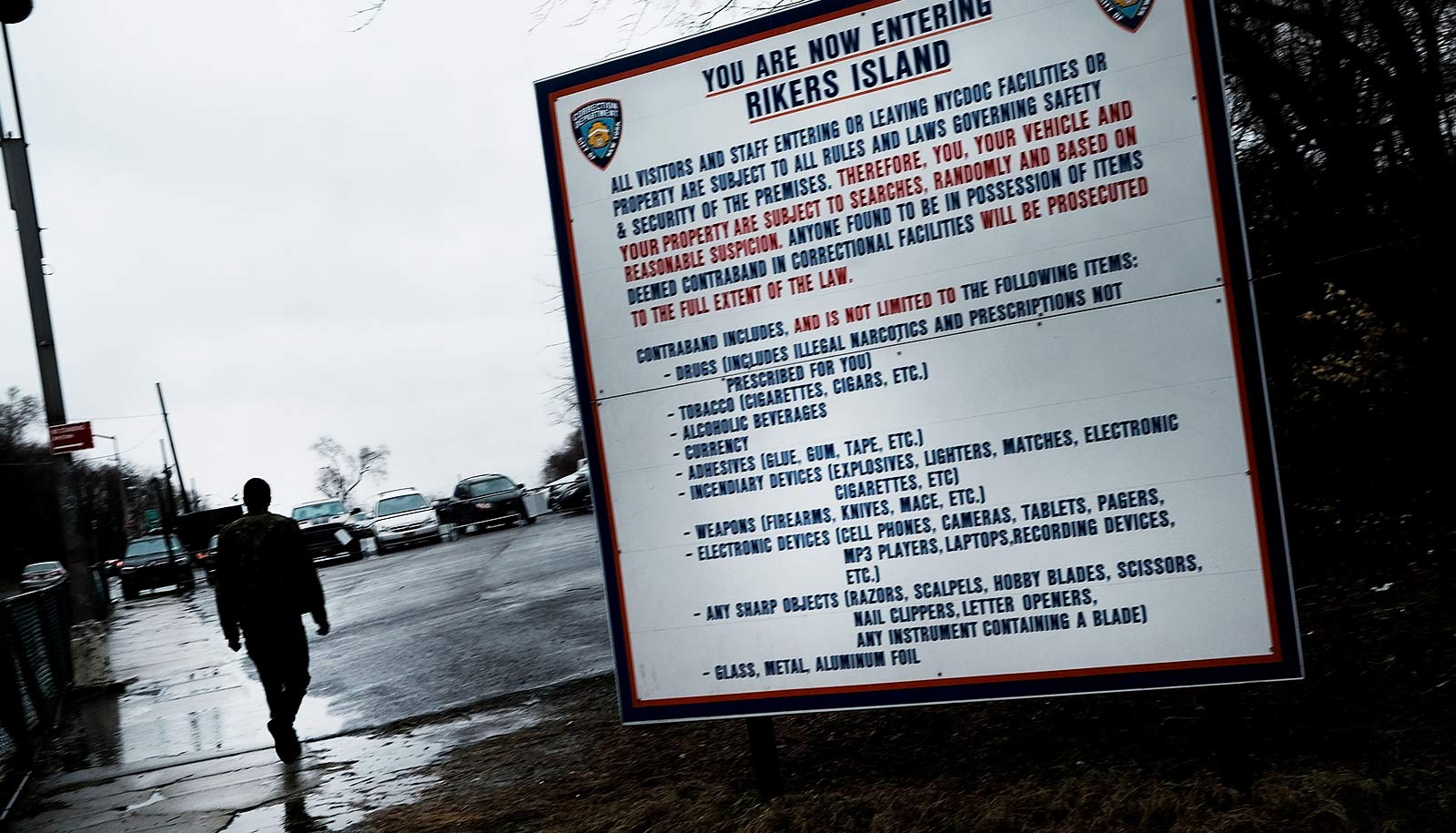

In places like New York City where the virus is already prevalent, Nagin says it’s inevitable that it will turn up in jails and prisons—such as the large numbers of cases already reported among inmates and guards on Riker’s Island, for example.

Act fast to stem COVID-19 in prisons

The threat of a humanitarian crisis puts pressure on officials to act fast if they want to take steps to reduce incarcerated populations before a wave of disease hits leading to a spike in potentially serious medical needs.

“A prison in a pandemic becomes akin to a cruise ship—people are crowded into a shared space that they cannot leave,” he says, pointing to recent incidents of cruise ships becoming incubators for the coronavirus.

“At least on cruise ships you can humanely enforce social distancing—and then [passengers are] quarantined in a cruise cabin, not a jail cell. Managing disease in a jail is much more difficult.”

In situations where the infection rate is currently low in a jail, the idea of releasing some number of inmates (and not admitting anyone else) remains sound public policy.

However, once the virus becomes well-established in a correctional facility, it becomes too late to release inmates responsibly, since sick individuals need quarantine and proper medical treatment.

“Once this emergency passes, we may realize the need and practicality of being more selective in how we use jails…”

In recent years, many jurisdictions in the US have taken steps to reduce mass incarceration. In some cases, that follows federal legislation like the 2018 FIRST STEP Act—which, among other reforms, expanded “compassionate release” for inmates with terminal illnesses.

In other cases, reductions have been in response to court mandates that address overcrowding, as happened in California following a 2011 Supreme Court decision. Other states have proactively sought to reduce prison populations, using incentives for early release and other strategies.

“But in the past, reductions in incarcerated populations have happened over the course of years, not all at once,” Nagin says.

Jails will probably first release inmates awaiting trial and those considered a low risk to public safety, Nagin says.

“The courts are closed down right now. You have people who are in jails awaiting trial, but no trials are taking place. Say you release some of them, those cases will still need to be heard once this period has passed.

“The real policy question once we get past this crisis will be choosing which cases to prosecute—those decisions will likely be in the hands of local prosecutors, and I can imagine prosecutors deciding that certain kinds of offenses will not be prosecuted, or changing plea bargaining practices to make deals to reduce sentences.”

Risk to police officers

Just as prisons and courts face an unprecedented situation due to the coronavirus, so too do police officers.

“My guess is that certain kinds of crimes are going to go down during this period, like robberies for example. But during social distancing, people [in the same household] are spending more time together and under a lot of stress.

“So, I think it’s likely that domestic disputes—in which the police have to regularly intervene—are going to increase markedly,” says Nagin, adding that many domestic disturbances require officers to enter a home and try to mediate the dispute.

“To arrest someone, you need physical contact with them. When the police need to intervene in a situation, the rules of social distancing cannot apply,” he says.

The coronavirus outbreak could prompt police departments to create more non-physical mediation and de-escalation strategies that minimize physical contact and use of force. Such modifications, if proved effective, could last beyond the crisis period.

In addition to policing, Nagin says he believes the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic could result in various long-term changes to the country’s approach to incarceration, jails in particular.

“Once this emergency passes, we may realize the need and practicality of being more selective in how we use jails, especially for things like pre-trial incarceration and as punishment for minor offenses like unpaid fines and public disorder.”

Further, policymakers could similarly reconsider how we use imprisonment, and possibly sending fewer people to state prisons for minor offenses.

“Sometimes a shock like this can trigger changes in policy which can have an enduring impact,” Nagin says.

Source: Carnegie Mellon University