People bearing the brunt of climate change-related problems are now the same communities at a disadvantage in fending off the novel coronavirus, say researchers.

Just like the risks posed by climate change, the novel coronavirus is hitting communities unequally, falling largely along racial and socioeconomic lines, as new total infections in Massachusetts surged in the last week to over 41,199.

In Chelsea, Massachusetts, a city just outside of Boston where about 65% of residents are Latinx, infection rates are the highest in the state.

“Populations that are disproportionately affected by the coronavirus are largely the same as those at risk of more significant climate change impacts, including actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions that could further perpetuate inequities,” says Cutler Cleveland, professor of earth and environment at Boston University and associate director of its Institute for Sustainable Energy.

It’s a familiar pattern, and with evidence linking long-term air pollution exposure to more serious COVID-19 infections, the work of addressing health disparities due to public health crises has taken on a renewed sense of urgency.

“If we don’t intentionally embed equity, it just doesn’t happen…”

“Low-income households, people of color, and the elderly often lack the resources and capacity to respond to the health and climate crises, and many public health and climate policies do not include strategies to specifically address the needs of vulnerable populations,” Cleveland says.

Cleveland is one of the lead researchers for the Carbon Free Boston Social Equity Report, which last year laid out solutions for lowering greenhouse gas emissions without worsening social inequalities in Boston, and ideally, universally improving social and health outcomes by transitioning away from fossil fuels like natural gas and oil.

The social equity report reveals that the risks of climate change are greater for people who are struggling to pay monthly electricity bills, or who don’t speak English as a primary language, or have less access to transportation.

Lower income neighborhoods and communities of color also are more likely to experience higher exposure to air pollution, according to research from Boston University School of Public Health researchers Jonathan Levy and M. Patricia Fabian, who in 2018 found that Boston’s black and Latinx families experience 38% higher air pollution concentrations relative to white families.

“The reality is that most people fall into a category that is considered socially vulnerable or marginalized.”

Another relevant study, done in 2003, found that patients from areas with heavy air pollution were twice as likely to die from SARS, a coronavirus similar to SARS-CoV-2, compared to people from regions with low pollution. Currently, 82% of COVID-19 patients at Boston Medical Center are black or Hispanic, reflecting the pandemic’s disproportionate toll on minority communities.

“If we don’t intentionally embed equity, it just doesn’t happen, and when it doesn’t happen we make things worse for people who are already struggling,” says Atyia Martin, CEO and founder of All Aces, an organization that works to embed racial equity into institutional and workplace initiatives. Martin and her team worked closely with Cleveland and collaborators on the social equity report, which has since been taken into consideration in the city’s updated climate action plan.

“The reality is that most people fall into a category that is considered socially vulnerable or marginalized,” says Martin. “We’re not talking about a small group.”

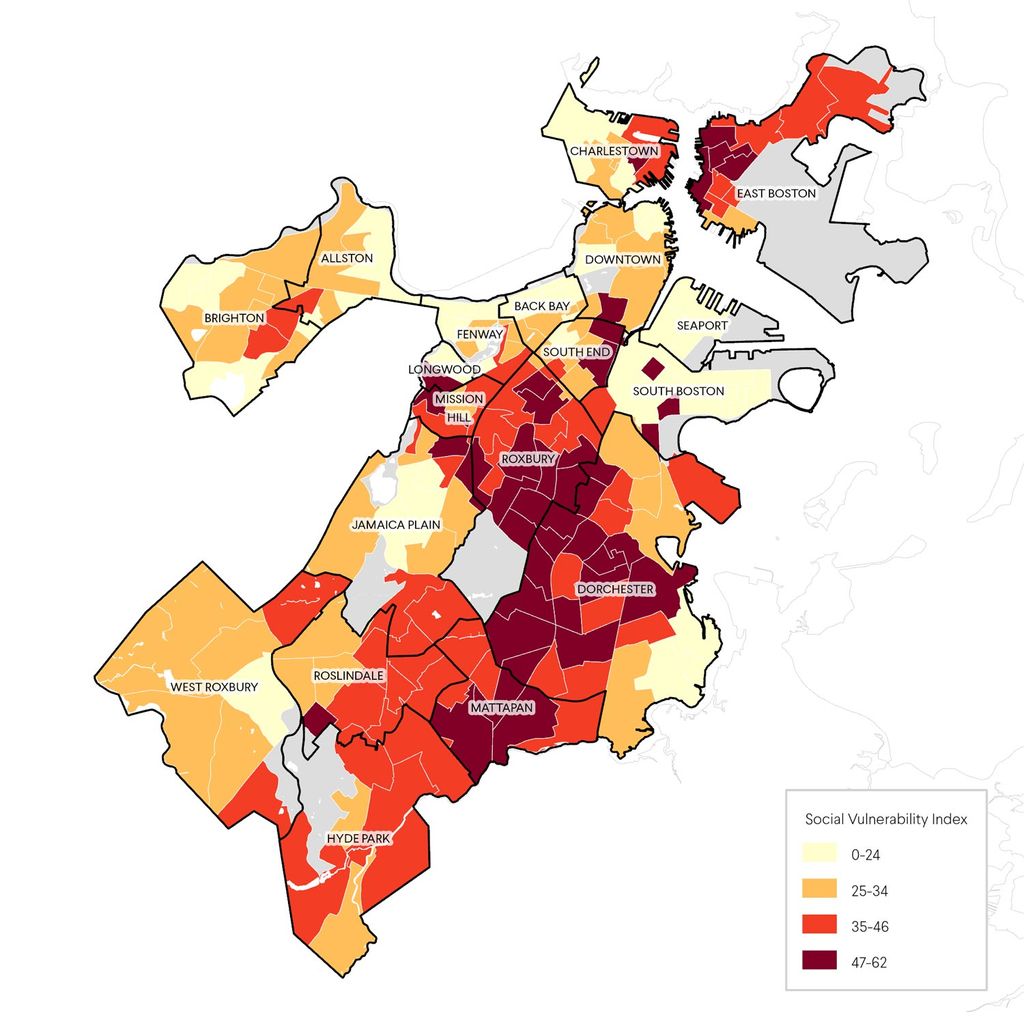

In order to closely examine how social equity disparities play out across the city of Boston, researchers created a social vulnerability index, combining US census and population data to determine which neighborhoods are considered to be at particular risk of energy, food, medical, or financial insecurities. These neighborhoods—with Dorchester, East Boston, Hyde Park, Mattapan, Mission Hill, and Roxbury coming in at the top—have a host of similarities, such as average lower median incomes, less homeownership, fewer MBTA stops, and older housing stock, which translates to higher energy burdens for families who must devote a larger fraction of their income to fuel and electricity.

With this in mind, researchers identify how Boston can use emissions-reduction strategies within four biggest emission sectors—buildings, transportation, waste, and energy—to address these historical inequities and create thoughtful climate policy that avoids unintended consequences.

“If all we did was convert to clean energy, utility bills would go through the roof,” explains Cleveland, which would exacerbate the financial burdens on vulnerable communities. That’s why, he says, old buildings need to be retrofitted for increased heating and electrical efficiency alongside a transition to clean energy.

“No cold weather city in the world has figured out how to comprehensively create a system where you thermally decarbonize your energy services, while also improving energy efficiency,” says Cleveland. Add in Boston’s extreme lack of affordable housing, making many neighborhoods vulnerable to gentrification and displacement, and the number of renters and multifamily homes, and city planners and policymakers have themselves a head scratcher.

But moving away from dirty fuels would have a great impact on the disparities that respiratory illnesses like COVID-19 make clear. “Clean energy reduces air pollution, which improves overall public health, and disproportionately benefits socially vulnerable populations. Investment in energy-efficient buildings creates healthy indoor environments,” Cleveland says. Simply put, clean air, in general, means fewer people getting sick.

It also offers the communities most impacted by climate change new opportunities to create businesses and jobs that can help make the transition to clean energy a reality, in turn improving the health of their own communities.

“We are going to need people who can do this work. Why not figure out a way to help people create the infrastructure necessary to start their own businesses?” says Martin, who also emphasizes the need for communities to be included in the city’s decision-making process.

Going forward, Cleveland hopes to see Boston prioritize and develop metrics for success in the area of equity, and regularly update progress in a visible and transparent manner—an issue that has also been raised with data collection on COVID-19 patients.

“More effective climate and public health policy requires ‘bottom-up’ individual changes,” Cleveland says. “Plus ‘top-down’ changes by government and business.”

Source: Boston University