In Boston, stay-at-home orders to reduce the spread of COVID-19 cut morning rush hour traffic, which led, almost instantly, to cleaner air, researchers say.

“It is absolutely real,” says Lucy Hutyra, an associate professor of earth and environment at Boston University who monitors carbon emissions and air pollutants around Boston and the state of Massachusetts.

“It’s as if I magically implemented our most ambitious emissions reduction policies. That drop is astounding.”

Over the last month, since Governor Charlie Baker issued a stay-at-home advisory on March 23, Hutyra has continued tracking air quality using traffic data from the Massachusetts Department of Transportation, as well as air sensors her team has placed around the Boston University Charles River Campus and the city of Boston.

She has looked at how many cars are on the road in two locations, one in Newton and the other at the intersection of I-495 and I-95, finding a 50% to 60% decrease in traffic.

“It’s as if I magically implemented our most ambitious emissions reduction policies,” Hutyra says. “That drop is astounding.”

Along with plummeting emissions from traffic, carbon emissions in Boston overall have fallen by an estimated 15%, following a pattern observed around the world in areas where people have sheltered in place to avoid infection with COVID-19.

“This gives us a taste of what our emissions might look like if we managed to convert our vehicle fleet to clean electricity, or if traditional commuters found other ways of getting into the city or working from home without relying on emissions from their own individual tailpipes,” says Jeff Geddes, assistant professor of earth and environment.

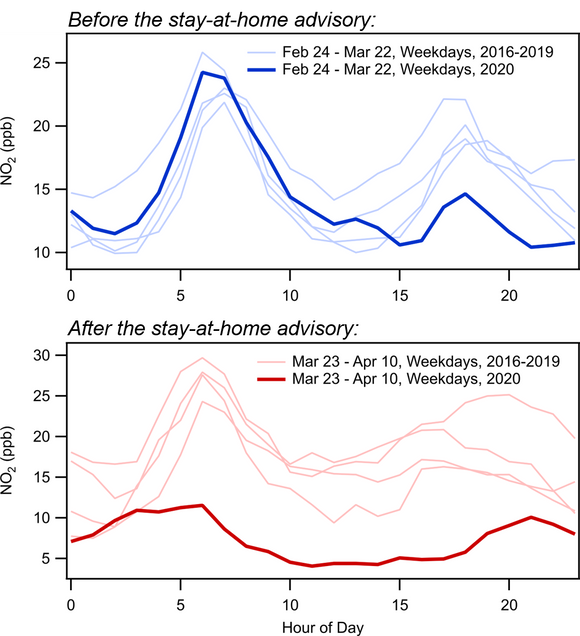

Geddes tracks reactive nitrogen oxides, an indicator of fossil fuel combustion activities largely due to commuter traffic and trucks, a key ingredient of the atmospheric chemistry that leads to smog.

Despite admitting that it’s an emotionally challenging time to run these types of experiments, Geddes has continued his work throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, finding that traffic-related emissions of nitrogen dioxide have gone down by at least 50% compared to this time last year in Boston.

Because nitrogen oxide is associated with fossil fuel combustion, its presence in the air is an indicator of other dangerous, and often unmeasured, pollutants such as ultrafine particles and toxic organic compounds, which have also decreased.

It’s hard to say what this means for the long term, but “as monitoring continues, and we gather evidence across a variety of platforms, including satellite measurements, we should be able to draw further insights,” Geddes says.

Hutyra points out that emissions will likely bounce back to their original levels like they have after past crises that have similarly brought the world to a standstill, like the Great Recession in 2009 and the September 11 terrorist attacks in 2001.

“This isn’t enough to have a long-term effect since we haven’t structurally changed anything that would reduce CO2 emissions in the long run, but it depends on what comes next,” says Hutyra, who plans to continue watching how people get themselves around the city.

“I’m sure there will be people who discover they can work from home more, start riding bicycles, and some people who might never get on public transportation again.”

Source: Boston University