Voters, policymakers, the media, and political analysts all misunderstand the influence of campaign financing, argue two social scientists in their new book.

When in 2010 the US Supreme Court ruled in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission that companies and labor unions enjoy the same right to political speech as individuals, many restrictions on money in American politics went out the window.

“Americans believe, for instance, that super PAC spending dominates campaigns, which is false.”

Subsequently, so-called super PACs—political action committees that are financed in part by large corporations, their multibillionaire shareholders, or powerful unions—can pour hundreds of millions of dollars into political campaigns, as long as their efforts are independent of candidates.

While most political observers would agree that super PACs are a dominant force in US politics, many would also argue they’re a nefarious influence. The influx of large sums of money into politics damages trust in government, suppresses voter turnout, puts corporate interests first, and results in corruption—so goes the common narrative.

That’s why campaign finance reformers, politicians, and academics alike have been arguing for decades that US democracy is imperiled by a threat that permeates all of politics—money.

But is that narrative accurate? The authors of the new book, Campaign Finance and American Democracy: What the Public Really Thinks and Why it Matters (University of Chicago Press, 2020), argue it’s not.

David Primo, a professor of political science and business administration at the University of Rochester, and Jeffrey Milyo, a professor of economics and chair of the economics department at the University of Missouri, say the reality is very different.

Campaign finance reform won’t fix things

The duo argues that campaign finance reform is not a “cure-all for what ails American democracy—at a time when it is viewed by many academics and practitioners as essential medicine.”

“Americans believe, for instance, that super PAC spending dominates campaigns, which is false,” says Primo.

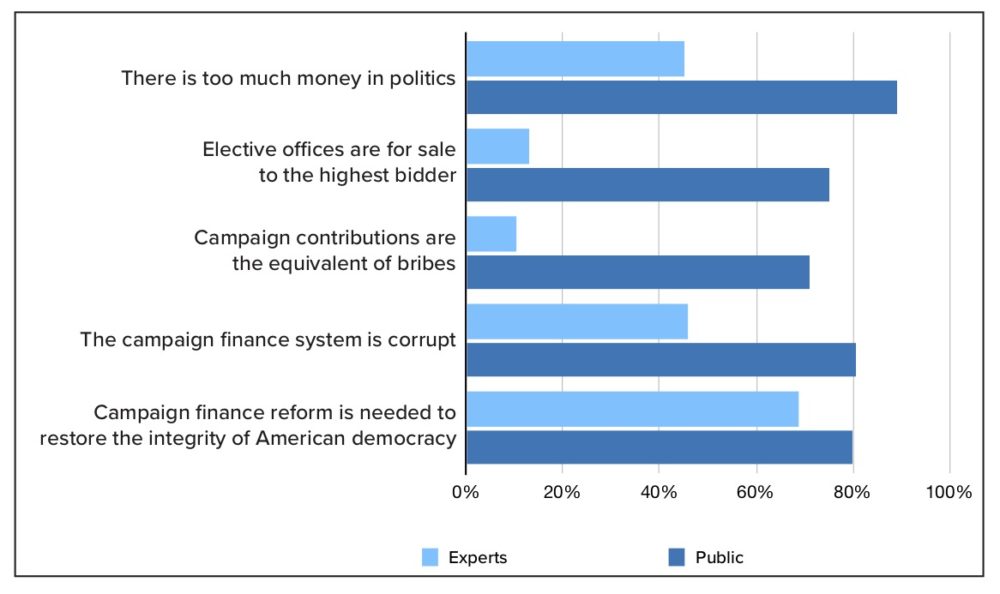

Primo and Milyo surveyed a total of 4,000 Americans in 2015 and in 2016—and about 150 experts in 2017—about their views on money in US politics. They also collected survey data on trust and confidence in government spanning three decades to study the effects of changes in campaign finance laws on trust.

Having aggregated the results of decades of survey responses, the authors conclude that changes in state-level campaign finance laws—where most changes in the laws take place, making it an ideal testing ground for social scientists—have little to no effect on attitudes toward government, contrary to conventional wisdom.

The finding, the authors argue, is perhaps the book’s most important conclusion, as it calls into question four decades of legal justifications for campaign finance reform.

What do Americans think?

The researchers’ other key findings on campaign finance include the following:

- While the public is very cynical about the role of money in politics, people are also skeptical about the potential for reforms to dramatically alter the political process.

- Americans do not see campaign contributions as uniquely corrupting.

- Public opinion does not offer a strong foundation for expanding campaign finance regulations: the argument that reform will improve trust in government or public perceptions of democracy does not hold up in the collected data.

- Part of the conventional wisdom surrounding campaign finance—that elective offices are for sale to the highest bidder—is false, while other beliefs about money in politics are suspect, overstated, or both.

- The public is largely uninformed about the basics of campaign finance regulations.

- The public’s attitudes toward money in politics are malleable. Beliefs about whether political speech should be protected often depend on the identity of the speaker.

- Americans are polarized on campaign finance reform proposals, with liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans having very different perspectives—especially if they follow politics.

- Americans who understand the informational benefits of campaign spending are less likely to support campaign finance restrictions.

- The “rigged rhetoric” used by reformers to discuss money in politics is in some cases more harmful to confidence in elections than the “rigged rhetoric” used by President Donald Trump.

- The Citizens United decision has not reduced trust and confidence in government, as critics of the Supreme Court ruling had feared.

In their book, the first after the Citizens United decision that contrasts public opinion and the scientific consensus on the role of money in American politics, Primo and Milyo set out to uncover what the public thinks about money in politics, what drives the perceptions, and why it matters.

They looked at whether public opinion regarding corruption and the undue influence of money in politics is connected to reality, and whether changes in campaign finance regulations are likely to affect public attitudes toward government.

It’s not so much that Americans are off base; rather, they are simply fed up with politics writ large. Money is just a convenient bugaboo.”

“It’s not surprising that Americans believe the political system is rotten to the core—that is the incessant message they receive from the media, politicians, reform groups, and scholars,” the authors write. “These elites nurture the public’s cynicism with their rhetoric and in turn use this cynicism as evidence of the need for reform.”

They add, “Money in politics, these elites tell us, is to blame for a wide array of ills in American society that threaten democracy: moneyed interests buying elections, rampant corruption, and declining trust in government. The elites are wrong, yet the American public believes them.”

Author Q&A

Here, the authors explain their findings and why money in politics may not be as bad as some people fear:

You write that the elites are wrong that moneyed interests can buy elections, that corruption is rampant, and that trust in government has been declining. Yet the American public believes those elites. What exactly is wrong with that widely held view?

Primo: We are taking on the belief that money is to blame for all that ails American politics. The reality is very different. Money does not buy elections—witness Michael Bloomberg’s failed attempt to secure the Democratic nomination for president. Corruption is not rampant—bribery scandals still garner attention precisely because they are unusual. And Americans’ mistrust of government is not driven by levels of campaign spending or the stringency of campaign finance laws.

Is public opinion regarding corruption and the undue influence of money in politics largely off base, then?

Milyo: It’s not so much that Americans are off base; rather, they are simply fed up with politics writ large. Money is just a convenient bugaboo. Consider this: in our research, we show that Americans have become so disgusted with American politics that they view even conventional behavior, like trying to secure favorable media coverage, as corrupt. We looked at decades of survey data and failed to find any evidence that stricter campaign finance laws improve perceptions of government.

Primo: What’s more, American attitudes about whether a behavior is corrupt are in part determined by partisanship. An action taken by a Democratic politician will be viewed differently from the same action taken by a Republican politician, depending on the partisanship of the respondent. When it comes to voters, a liberal Democrat is much more inclined to protect corporate political speech when the brand doing the talking is Ben & Jerry’s as opposed to ExxonMobil, for example. This again raises concerns about public attitudes as the basis for justifying campaign finance restrictions.

Would you argue that Citizens United was not a poor decision, or just not as poor as most believe?

Primo: Citizens United is a widely misunderstood decision that has a mythology around it. It did not permit foreign involvement in elections. It did not alter disclosure rules. It did not allow corporations to make contributions to candidates for federal office. What it did do was expand the ways in which groups of individuals, such as unions and corporations, could be involved in the political process. Corporations are routinely called on by activists to take political positions on social issues, yet many of these activists, I suspect, oppose Citizens United.

The public doesn’t believe that campaign finance reform would really work, yet the experts you polled think reform makes sense. So—is it necessary or not?

Milyo: If the goal is to improve perceptions of government, the answer is no. The empirical evidence simply isn’t there. Put another way, if campaign finance reform were a potential cure for a disease in a clinical trial, it wouldn’t get approval. Campaign finance reform really can’t fix competitive partisan politics in a pluralist democracy that values free expression and diversity of opinion.

What part of campaign financing is harmful and what part of campaign financing looks harmful but proves to have no or little effect on a politician’s voting behavior?

Primo: I would turn this question on its head and talk about the benefits of campaign spending. There is ample social science evidence that campaign spending improves turnout and voter knowledge. We hear too little about these benefits. On the flip side, there is very little evidence that legislators are basing their votes on who gives them campaign contributions, though most political scientists agree that campaign contributions help maintain relationships with legislators.

What’s needed to restore the public’s faith in government? Or is that a utopian ideal?

Primo: That’s the million dollar question. Trust in American government began to decline in the 1960s and then plummeted in the wake of the Vietnam War and Watergate. It’s fluctuated since but has never recovered. What we do know is that Americans who share the same party as the president trust the government more than members of the out party, suggesting that trust is infused with a partisan component. As long as that is the case, it will be hard to move the needle on trust. It’s also worth asking whether some skepticism of government is healthy in a democracy—as it helps keep elected officials accountable.

Milyo: Why should people trust government? Rather than trying to artificially gin up trust via some magic wand, like campaign finance reform, maybe government officials need to act in a way that merits trust? Absent that, it is very healthy that Americans have a deep distrust of those that wield the coercive power of the state; it is probably the most important check on abuses of civil liberties and the main reason our republic has survived this long.

Source: University of Rochester