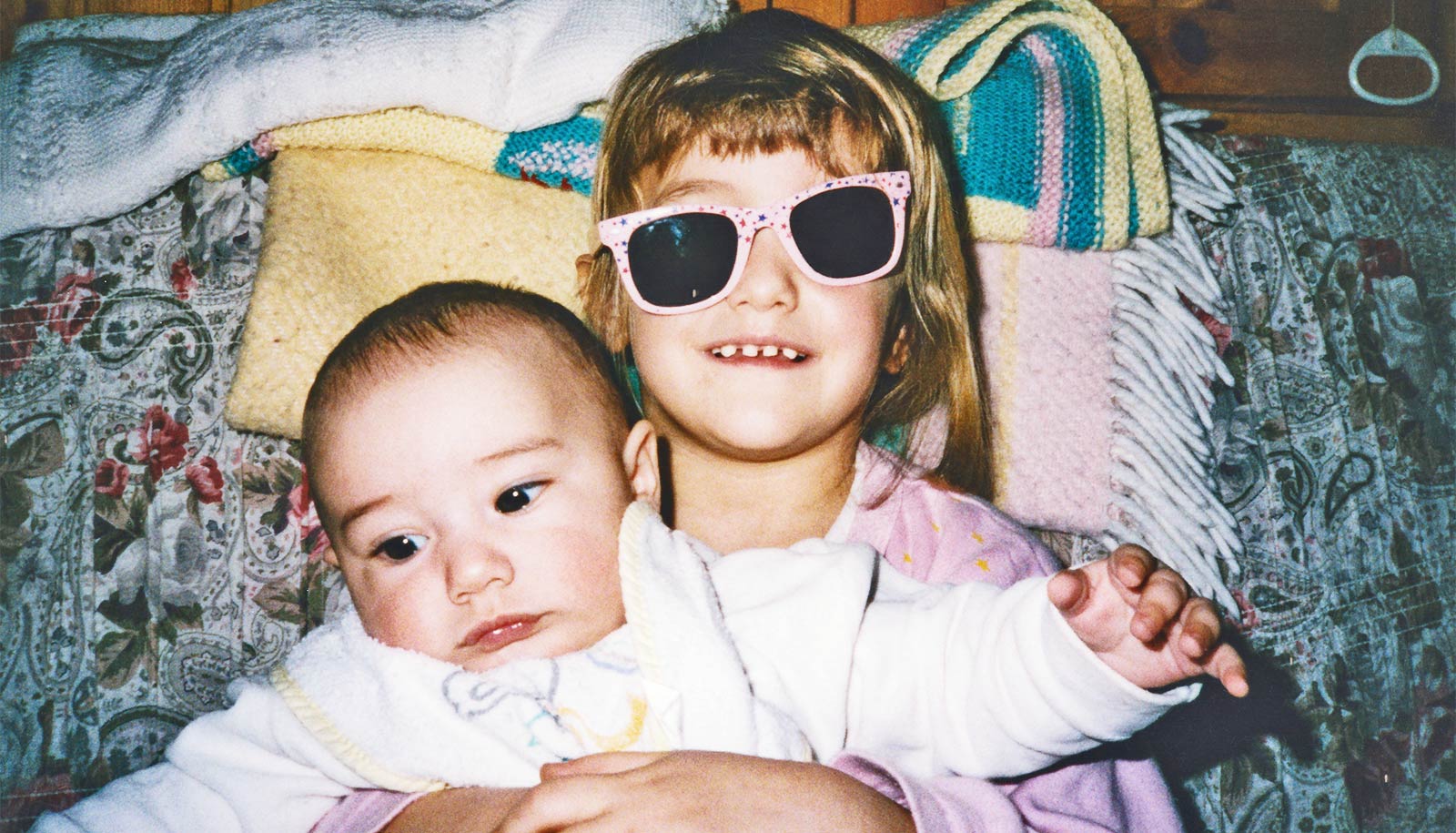

New research reveals how childhood sibling dynamics may shape billion-dollar financial decisions.

Many people know nothing about the mutual fund manager whose investment decisions affect the performance of their IRA and 401(k) accounts.

But the new research suggests it’s well worth one’s while to know who’s minding your funds—specifically their birth order—due to implications for how your fund performs.

Finance professor Vikas Agarwal, of Georgia State University and his coauthors at the University of St. Gallen share their findings in a new paper in the Journal of Finance, including that a mutual fund manager’s birth order could be a strong predictor of their investment behavior.

The researchers found that managers who were born later among siblings take more financial and regulatory risks. And although one may expect bigger risks to come with bigger rewards, the data shows otherwise: later-born managers tend to underperform their firstborn peers on nearly every risk-adjusted performance metric.

Agarwal and his coauthors analyzed decades of data for more than 1,400 US-based mutual fund managers who manage nearly 1,800 mutual funds. The researchers combined performance statistics with detailed family background information, including birth rank, sibling age gaps, and even parental income and education, sourced from obituaries, public records like US Census data, and databases like Ancestry.com.

This is one of the first studies to use these types of data to quantify how birth order affects mutual fund management.

“We did not use just a standard database—we had to analyze many different data sources to get the level of family details on each manager, because what we really wanted to understand is the root cause of this risk-taking behavior by later-born siblings,” says Agarwal.

“What we found is that it boils down to sibling rivalry, as later-born children may develop sensation-seeking traits as a way to stand out in the family.”

The study’s results are both striking and statistically robust. A manager’s birth order was strongly correlated with several key indicators of risk-taking. For every step down in birth order (from firstborn to second-born, for example), total fund risk increased by 0.37 percentage points annually. Active risk, that is how much a fund’s returns deviate from its benchmark, rose by 0.65 percentage points.

Later-born managers were also more likely to invest in so-called lottery stocks—companies with low prices, high volatility, and a small chance of outsized returns—such as biotech startups or meme stocks. This gambling-style behavior may resonate with sensation-seeking personality types but is often out of sync with investor preferences for stable, long-term growth.

Perhaps most notably, later-born managers were more frequently cited for regulatory or civil violations, according to data from FINRA’s BrokerCheck records, including infractions like late disclosures, misreporting, and customer disputes.

Findings show this extra risk-taking did not translate into better performance. On measures like the Sharpe ratio, which is a widely used financial metric to evaluate the risk-adjusted return of an investment or portfolio, information ratio, and peer-adjusted alpha, later-born managers consistently underperformed. The researchers estimate that about half of this underperformance can be traced to their preference for lottery stocks.

To probe the mechanism behind this phenomenon, the authors examined whether certain family conditions made the birth order effect stronger. They found that the effect was amplified in families with fewer parental resources and narrower age gaps between siblings.

“Siblings closer in age are fighting for the same resources as children, so we found this competitiveness stronger when the age gaps are smaller and parental attention is limited due to single parent or dual working parent households,” says Agarwal.

With trillions of dollars parked in 401(k)s and IRAs, understanding the behavioral drivers of fund managers is crucial for investors, advisors, and regulators.

“This is important because it’s not the fund managers’ money—it’s the money of the investors. And if these fund managers are taking risky, gambling-type decisions with other people’s money, then it has implications for the welfare of the investors who are investing in this mutual fund,” says Agarwal.

While birth order obviously isn’t something asset managers disclose in their prospectuses, it adds a new dimension to the ongoing debate about what makes a good fund manager. Beyond credentials and track records, personality traits rooted in early childhood may influence how aggressively a manager plays the market.

So next time you’re choosing a fund, you might just wonder: Is the person behind the portfolio a cautious firstborn or a risk-hungry youngest sibling trying to make their mark?

Source: Georgia State