Obesity may increase arthritis risk across generations, a new study with mice suggests.

Arthritis affects one in five Americans, and one in three Americans with obesity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

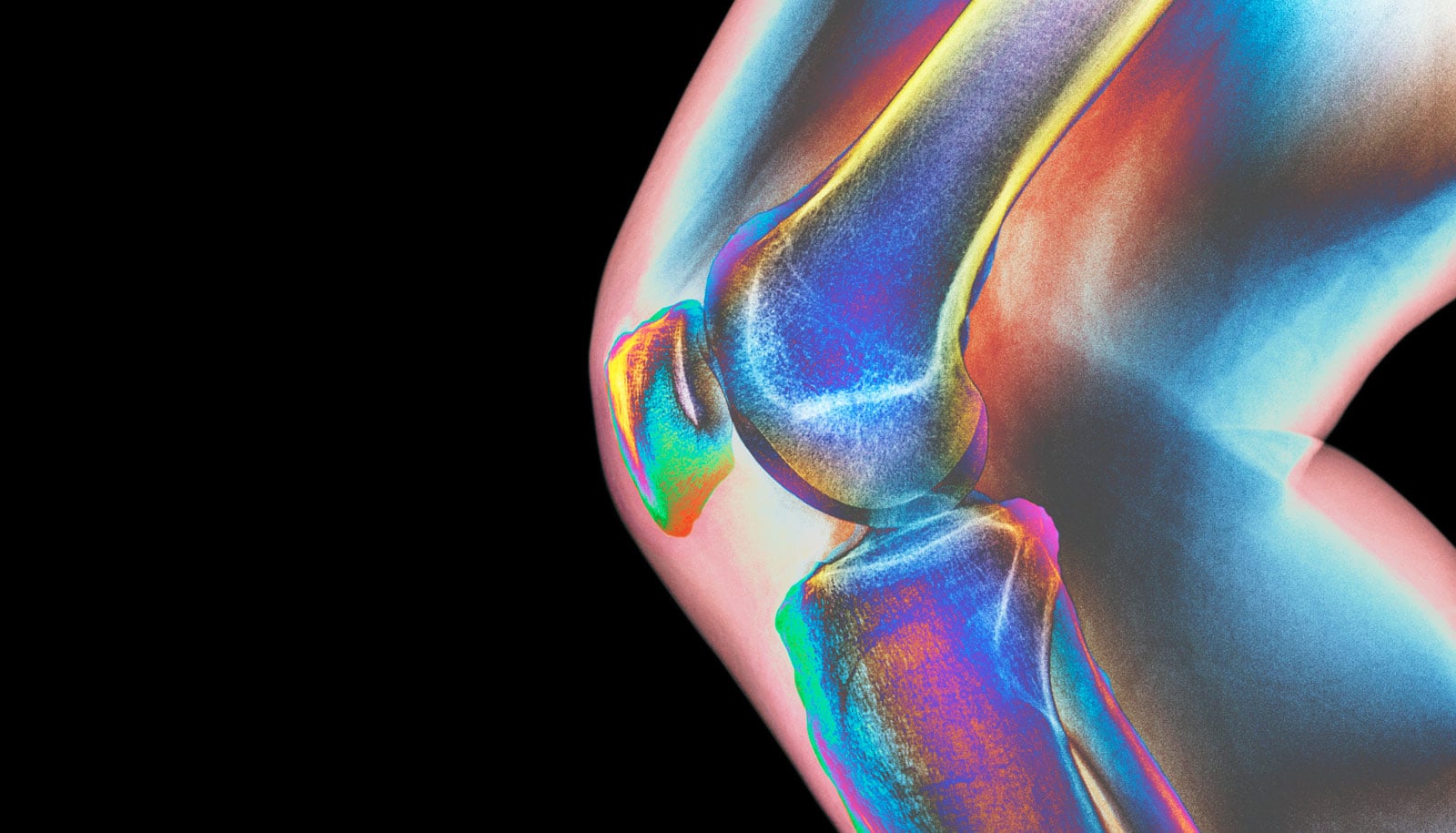

When researchers studied mice that became obese after eating a high-fat diet, they found that the animals had an elevated risk for osteoarthritis, which causes cartilage in the joints to break down.

Surprisingly, they also found that the mice’s offspring, even when fed a diet lower in fat, tended to gain nearly 20% more weight than the offspring of their littermates that had never been overweight.

In addition, they had a higher risk for arthritis. The same was true for the next generation of mice as well, which gained up to 10% more weight.

Arthritis affects 250 million people worldwide

“This study tells us that environmental factors can influence how genes behave and influence the risk for arthritis for multiple generations,” says senior investigator Farshid Guilak, professor of orthopedic surgery at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

“Arthritis prevalence is affecting many more people than it used to, more than 250 million people worldwide, and these findings suggest that obesity may help explain why the disorder is becoming so much more common.”

An analysis of more than 120 mice whose parents had consumed a high-fat diet showed that the offspring—despite having eaten a low-fat diet themselves—were significantly heavier and had more body fat than the offspring of mice that hadn’t consumed a high-fat diet.

Then, when those mice had pups—the grandchildren of the original mice—that third generation of mice also had higher levels of inflammatory molecules and cells in their systems than their littermates, despite never having been fed a high-fat diet. Higher amounts of those molecules, called cytokines, are linked to a variety of problems, including arthritis.

In fact, the third-generation mice had higher levels of molecules that cause inflammation, and lower levels of molecules that protect against inflammation. The children and grandchildren of the obese mice in the study also were more likely to have bone and cartilage changes that put them at risk for osteoarthritis.

“We can’t assume everything we found in these mice will turn out to be true for people,” says Natalia S. Harasymowicz, a postdoctoral fellow in Guilak’s lab and first author of the paper in Arthritis & Rheumatology. “But there’s more and more evidence that when parents eat a bad diet or smoke or abuse alcohol, the next generation is more likely to inherit a predisposition for diabetes, cancer, or other diseases. Here, we’ve shown the same appears to be true for arthritis.”

Inflammation plays an important role

Guilak, who also is director of research at Shriners Hospitals for Children-St. Louis, says that in the past, scientists had assumed that the relationship between obesity and osteoarthritis was a mechanical one: More weight puts stress on joints, eventually leading to the pain and stiffness of arthritis.

“We’ve known for years that obesity is the number one preventable risk factor for osteoarthritis,” Guilak says. “It turns out, however, that obesity also increases arthritis risk in body parts that don’t bear weight, like the hand or the thumb.”

Guilak’s lab has determined that inflammation plays a much more important role.

“What we find is that changes in mechanical loading that occur with obesity don’t seem to be the primary risk factors for arthritis,” he says. “Almost all of the risk is coming from either metabolic or dietary influences, and that risk is then passed down to subsequent generations.”

The animal’s genetic makeup doesn’t change to cause increased risk of arthritis. Rather, scientists refer to the changes as epigenetic, meaning that behavior—in this case, consuming a high-fat diet—changes the way genes work. It’s those changes that are passed on.

The National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the National Institute on Aging, the National Institutes of Health, Shriners Hospitals for Children, the Arthritis Foundation, and the Nancy Taylor Foundation for Chronic Diseases supported the work.