Deborah Archer discusses the past and future of diversity as a goal in college admissions pending a decision from the Supreme Court on affirmative action.

Affirmative action aims to address racial discrimination by recognizing and responding to the structural barriers that have denied underrepresented students access to higher education, and has been an integral part of many US college and university admissions policies since the 1960s and 70s.

“Our underlying admissions practices are far from meritocratic.”

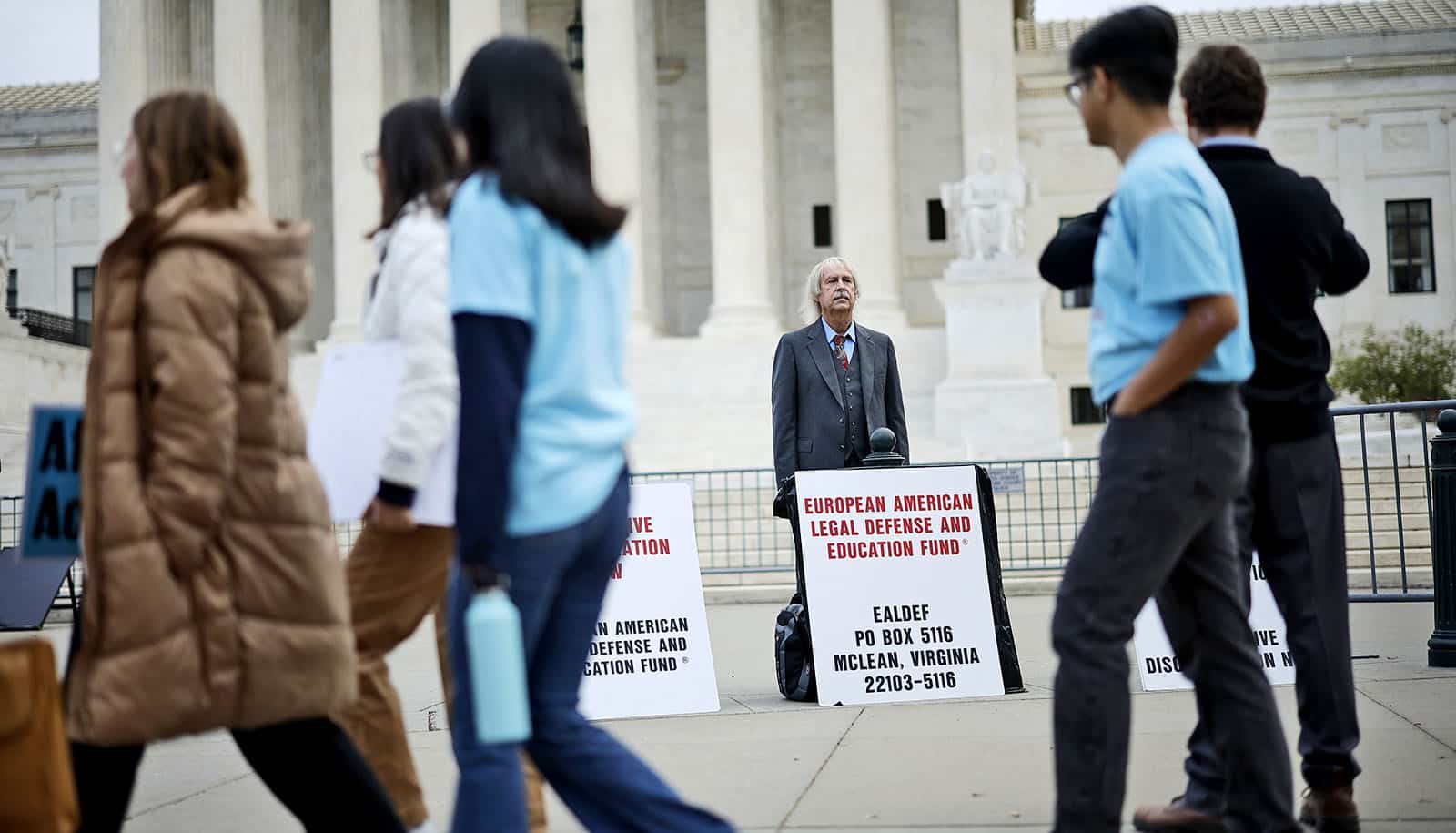

In October 2022, the US Supreme Court heard two cases filed by the Students For Fair Admissions (SFFA) organization, both challenging the constitutionality of affirmative action—or “race-conscious admissions policies”—at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina.

The SFFA argues that the 14th Amendment’s Equal Rights Provision makes these race-conscious admissions policies illegal, and experts say it is likely that the Court’s conservative supermajority will agree. Such a decision would enact a nationwide ban on affirmative action admissions policies in higher education across the country and is expected any day.

Archer, professor of clinical law at New York University and president of the ACLU, answers questions below about the history of affirmative action, and how higher education institutions can continue to strive for diversity if the SFFA cases prevail:

How is affirmative action currently implemented in college admissions processes?

Over the past 45 years, the US Supreme Court has repeatedly held that race-conscious admissions programs are constitutional, with substantial benefits that flow to individual students, the educational institution, and the larger society.

“Colorblindness is the antithesis of diversity and it exacerbates racial injustice…”

The law—which has been clarified in Bakke, two cases against the University of Michigan, and two cases against the University of Texas—says that race can be one factor among many in a holistic admissions program, provided that it is narrowly tailored and there is no race-neutral alternative that would achieve the same results. This is how affirmative action is implemented today and how it is implemented at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

In some states, they also use top 10% plans as part of their efforts to achieve a diverse class. With top 10% plans, high school students who graduate in the top 10% of their graduating class are guaranteed admission to the state’s public university. North Carolina is one of those states and its plan was at issue in the lawsuit against UNC-Chapel Hill.

What do you consider the biggest misconception about affirmative action?

One widespread misconception is that affirmative action is a preference. Affirmative action programs do not give a preference to any student because of their race. Preference is a loaded term and not an accurate one. The law is clear that admissions programs cannot give automatic preferences or points or reserve spots for applicants of certain races.

Another misconception is that affirmative action is an exception to a merit-based system. Race-conscious admissions programs are still merit-based admissions programs. Holistic review encourages admissions officers to look beyond conventional credentials and also consider context for the credentials and achievements.

Our underlying admissions practices are far from meritocratic. Many of the measures are better predictors of access to wealth than a student’s potential. And many students are admitted because they are the children of donors, alums, or faculty members. Moreover, racial inequality in K-12 schools feeds the racial inequality we see in higher education. Most K-12 schools are racially identifiable, and those racially identifiable schools do not have equal access to the resources and opportunities that are traditionally valued in the admissions process.

How would banning race-conscious admissions policies for universities impact similar diversity efforts in the workplace?

This decision should be limited to higher education admissions. Corporations and other organizations should not read something into the decision that is not there.

However, affirmative action is ground zero in a larger fight around racial justice. It is one step in a much larger effort to impose a colorblind framework on all of society and to make it impossible for public policy to address the deep and profound racial inequality. Colorblindness is the antithesis of diversity and it exacerbates racial injustice by preventing all of us from grappling with the ways race shapes our lives, experiences, and opportunities.

Has the Supreme Court ruled on affirmative action before?

Yes, the Court has ruled on this issue many times over the past 45 years. But these cases raise some new issues. First, previous cases were brought against public institutions using the Equal Protection Clause of the US Constitution. Here, they are suing Harvard, a private institution, using Title VI of the Civil Rights Act.

These cases are also different in the remedy they seek. They are not just asking that race not be a consideration in the admissions process—they have requested that “conduct all admissions in a manner that does not permit those engaged in the process to be aware of or learn the race or ethnicity of any applicant for admission.” And, yes, that means just what you think it means. This would require applicants to erase any trace of their race or ethnicity from their application for admissions. It would prevent an applicant of color from fully expressing their identity—and, in particular, those parts of their identity inextricably bound to their race.

If the SFFA prevails in these suits, and institutions of higher education cannot consider race in admissions decision-making, are there other avenues for them to continue to strive for diversity?

Nine states have prohibited the use of race and other protected characteristics in various settings, including university and college admissions. What institutions in those states have done is helpful and instructive in understanding what avenues could remain available to support diversity in higher education. Those efforts have included: Evaluating academic achievement in context; giving credit to students who have attended underserved and underrepresented schools; considering socioeconomic status and English language learner status; considering group or community demographics; and expanded outreach and recruitment efforts.

Source: NYU