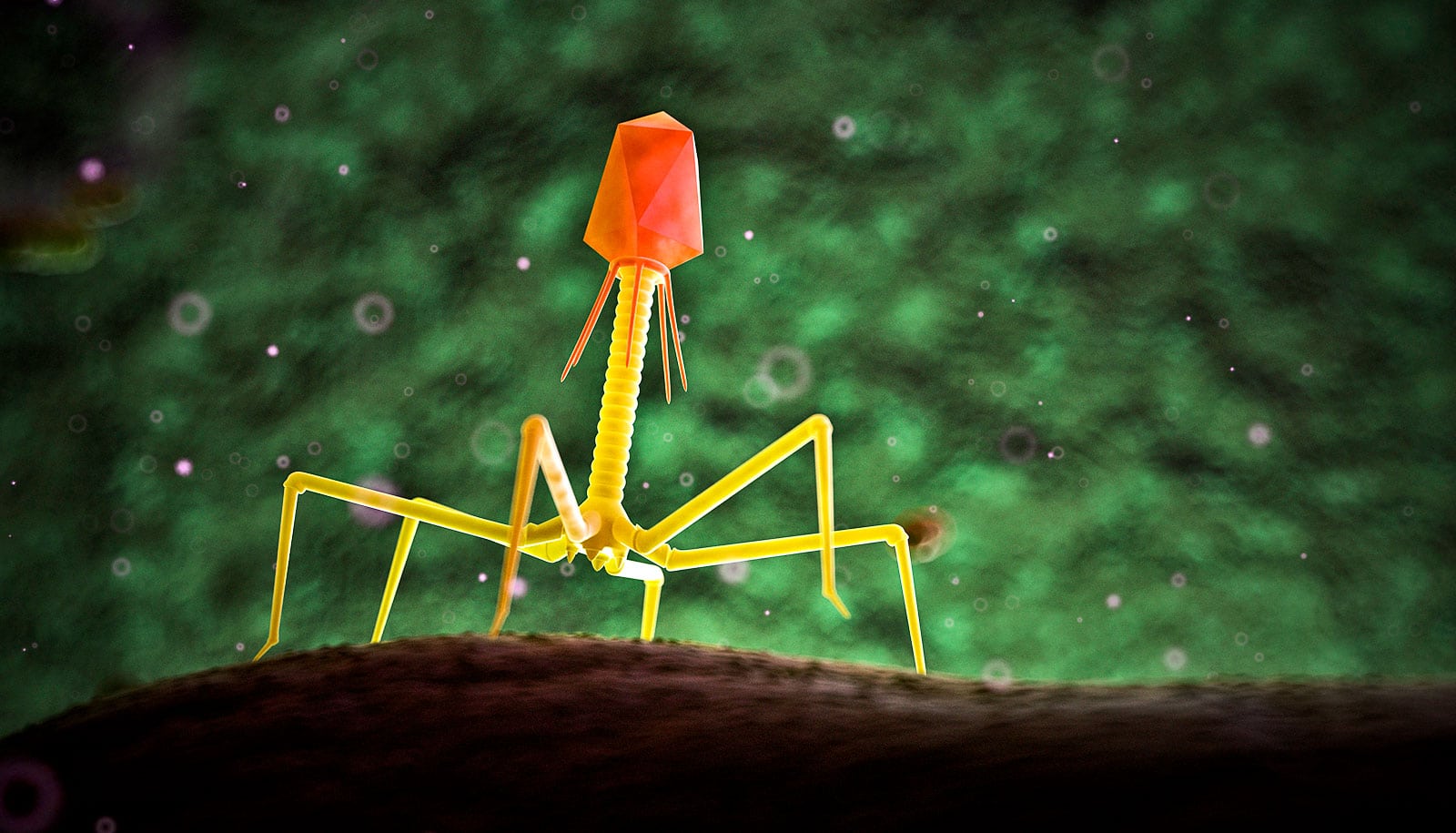

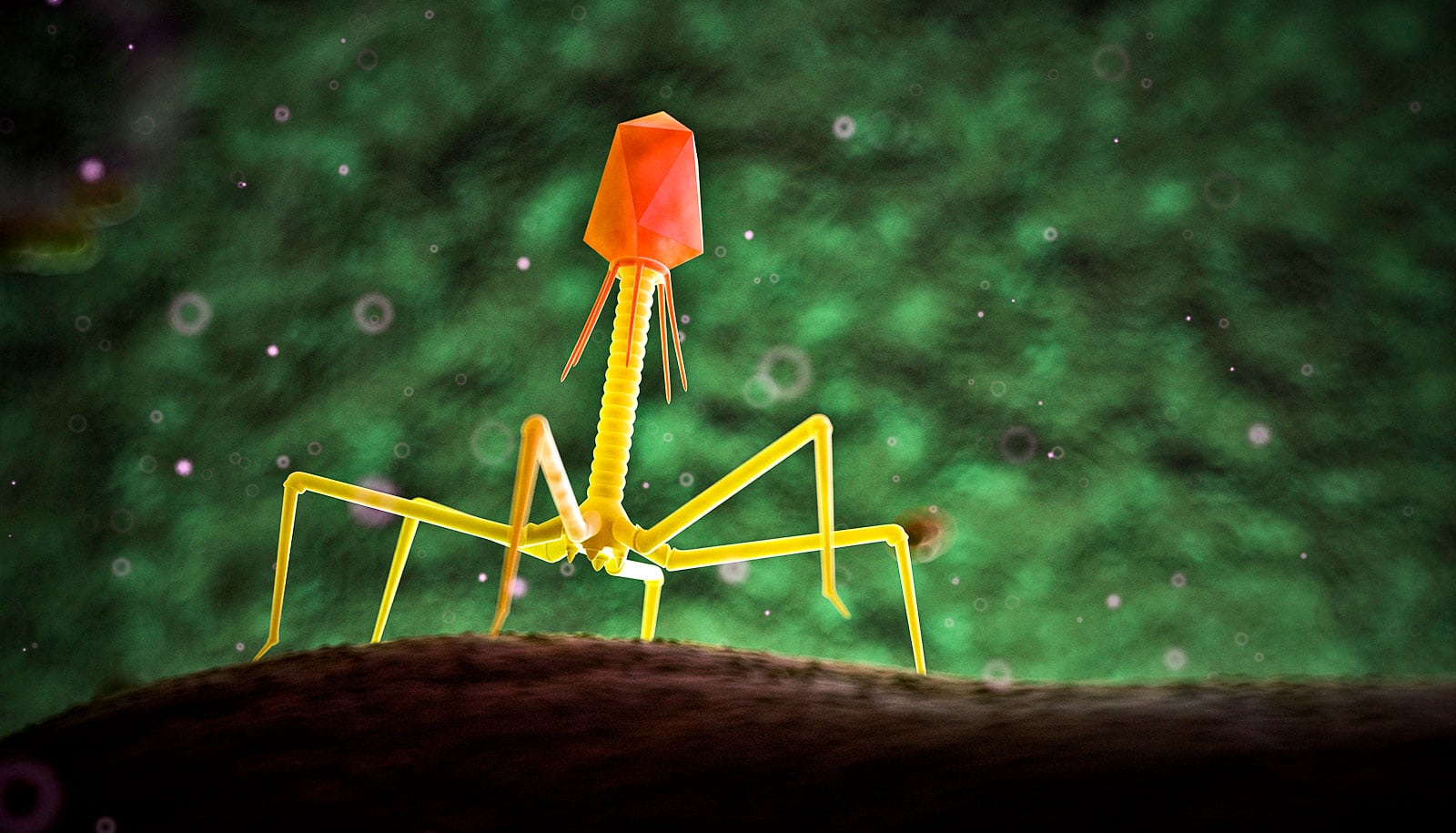

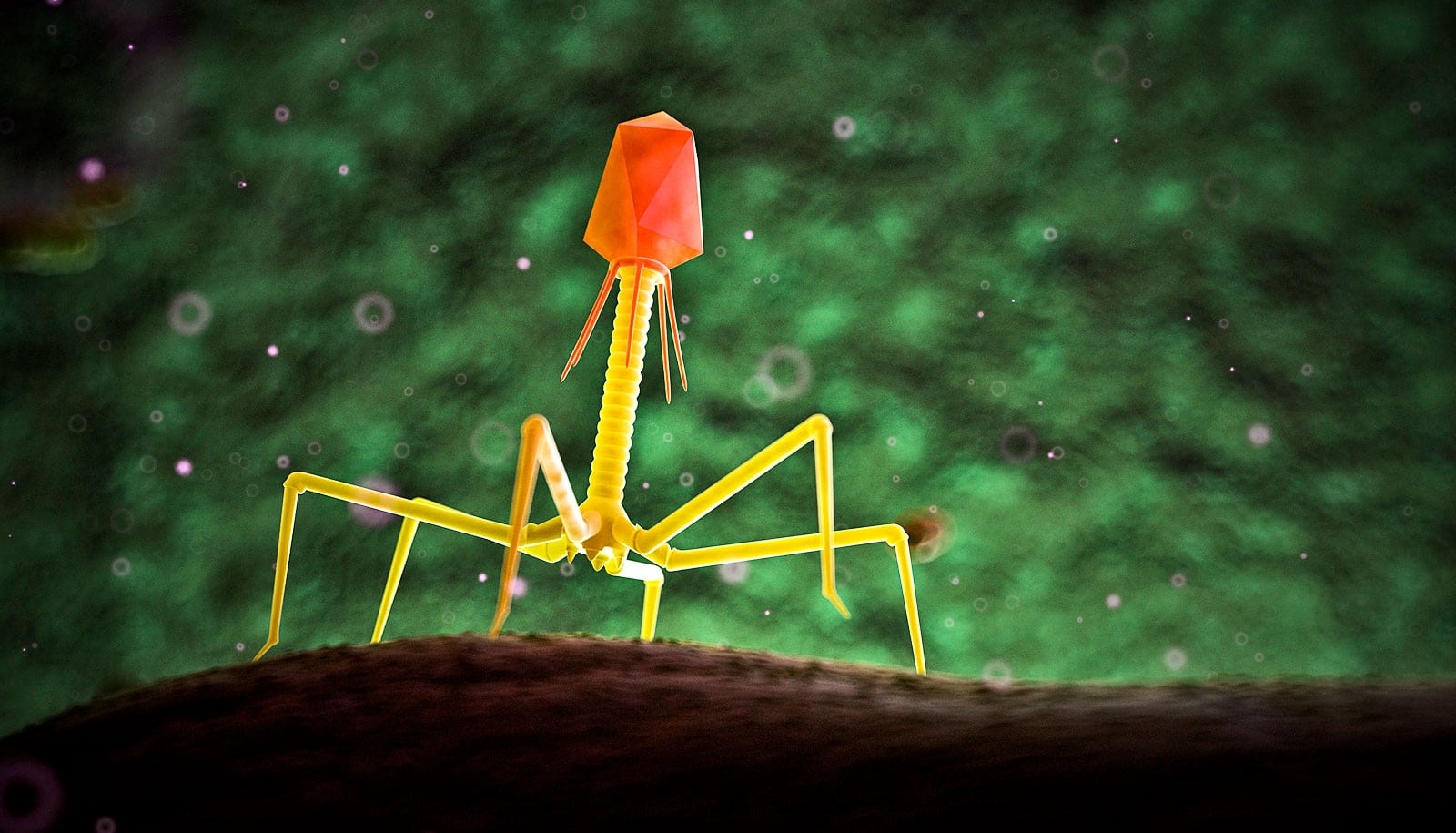

A new way to make phage DNA lays groundwork for better infection treatments, researchers report.

Researchers developed a method to construct bacteriophages with entirely synthetic genetic material, allowing researchers to add and subtract genes at will.

The findings open new ways to understand how these bacteria-killing viruses work and to create potential therapies to fight the worsening problem of antibacterial resistance.

There is massive variation among phages, but researchers don’t know the roles played by many individual genes, says Graham Hatfull, a professor of biotechnology at the University of Pittsburgh and one of the study’s lead researchers.

“How are the genes regulated? What happens if we remove this one or that one? We don’t have the answers to those questions, but now we can ask—and answer—almost any question we have about phages,” he says. “This will speed up discovery.”

The team constructed synthetic DNA modeled after two naturally occurring phages that attack Mycobacterium, which include the pathogens responsible for tuberculosis and leprosy, among others. They then added and removed genes, successfully editing the synthetic genomes of both.

They published their work in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Biologists are already able to create synthetic DNA, but the process is notoriously difficult for a certain class of phages due to their structure. DNA is built of two pairs of chemical building blocks, or base pairs, represented by the letters A, T, C, and G. The phages that attack Mycobacterium are about 65% G and C.

“Traditional methods of synthesizing DNA have technical problems with so-called ‘high GC’ DNA,” Hatfull says, as opposed to more easily editable genomes like those of E. Coli, which have ratios of base pairs that are closer to even.

To move past these obstacles, Hatfull worked with Greg Lohman of New England Biolabs, a company known for techniques enabling the design and assembly of synthetic DNA. Also integral to the work was Ansa Biotech, which has developed a process that overcomes the hurdles of synthesizing high GC DNA. The paper’s first author, Ching-Chung Ko, is a research associate in Hatfull’s lab.

The team was able to chemically synthesize DNA identical to two naturally occurring phages: BPs—a 40,000-base-pair virus used clinically to treat a bacteria that often infects people with cystic fibrosis—and Bxb1, which has 50,000 base pairs. They constructed the DNA in 12 sections and inserted them into a cell, which followed the instructions from its new genome: make phages.

Researchers and clinicians have become increasingly interested in phages as a response to fighting antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections. For perhaps as long as three billion years, phages and bacteria have evolved alongside one another, resulting in niches not unlike Darwin’s finches; one phage will only attack one specific kind of bacteria.

Exactly how phage genomes codify these relationships remains mostly a mystery.

Hatfull’s lab has freezers full of 28,000 phages that were found in dirt, ponds or even on rotting fruits. Finding one that will attack any particular strain of bacteria is a process of directed trial and error. When a clinician sends a sample from a sick patient, researchers use their experience, their library of about 5,500 phage genomes and plenty of petri dishes to search for a match tailored specifically to that patient.

Precisely altering phage genomes and observing how those changes affect behavior will be a game-changer that will both inform researchers’ understanding of how the phages work and, later, may allow them to engineer phages with broader applications.

“We’ve been surrounded by questions that we can’t always answer because we didn’t have the technologies to be able to do so,” Hatfull says. “This is a technological advance that enables us in principle to begin to answer many questions in a much simpler way than we could have done before.”

In addition, the ability to create entirely synthetic genomes will alleviate the need to keep tens of thousands of phages on ice, with duplicates of some, and sufficient backup power sources. Instead of storing biology, Hatfull hopes one day phages can be stored simply as information.

“And then, the sky’s the limit,” Hatfull says. “You can make any genome you want. You’re only limited by what you can imagine would be useful and interesting to make.”

Source: University of Pittsburgh