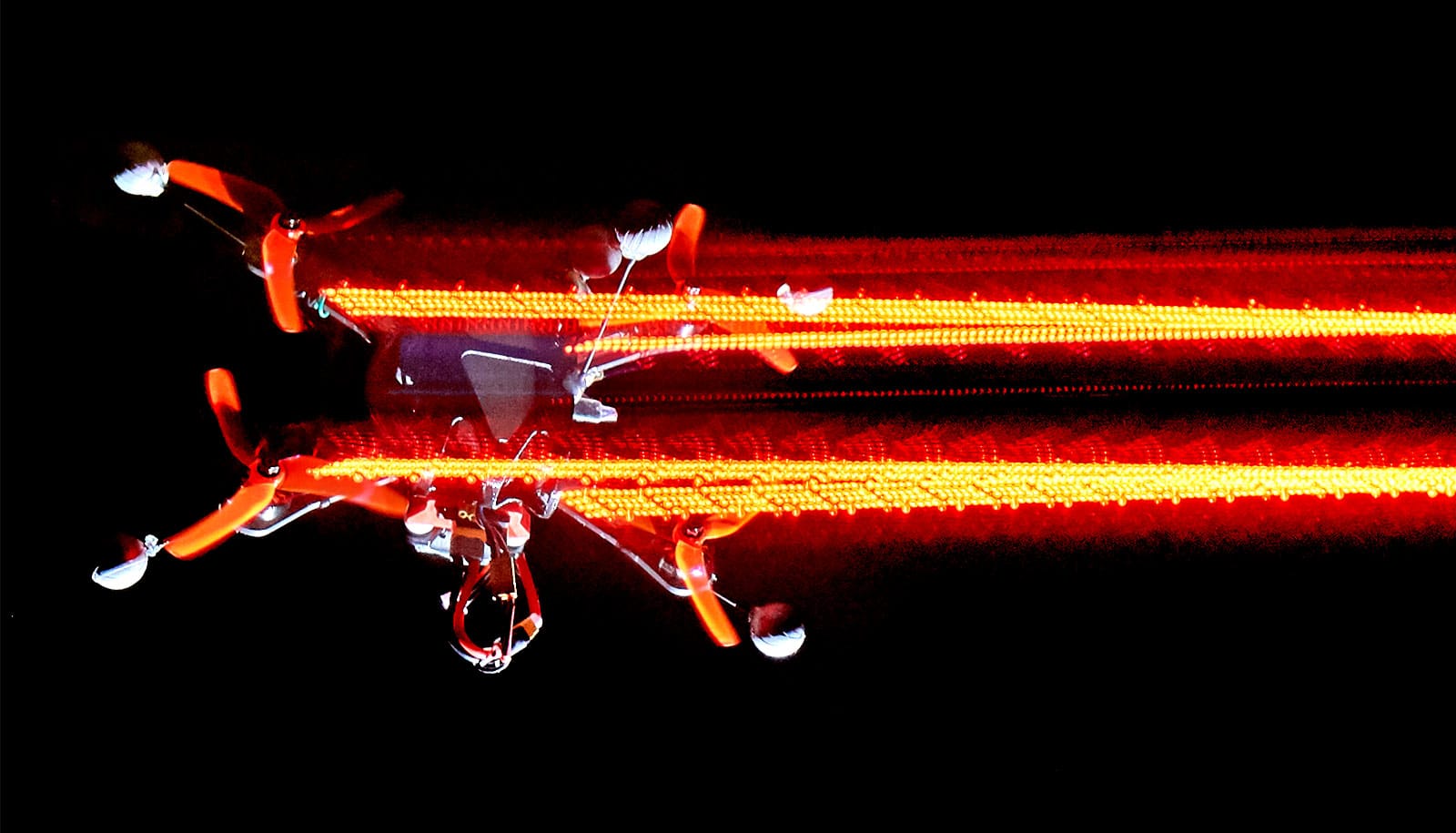

For the first time, an autonomously flying quadrotor has outperformed two human pilots in a drone race, researchers report.

The success is based on a new algorithm that researchers at the University of Zurich developed. It calculates time-optimal trajectories that fully consider the drones’ limitations.

“Our drone beat the fastest lap of two world-class human pilots on an experimental race track.”

To be useful, drones need to be quick. Because of their limited battery life they must complete whatever task they have—searching for survivors on a disaster site, inspecting a building, delivering cargo—in the shortest possible time. And they may have to do it by going through a series of waypoints like windows, rooms, or specific locations to inspect, adopting the best trajectory and the right acceleration or deceleration at each segment.

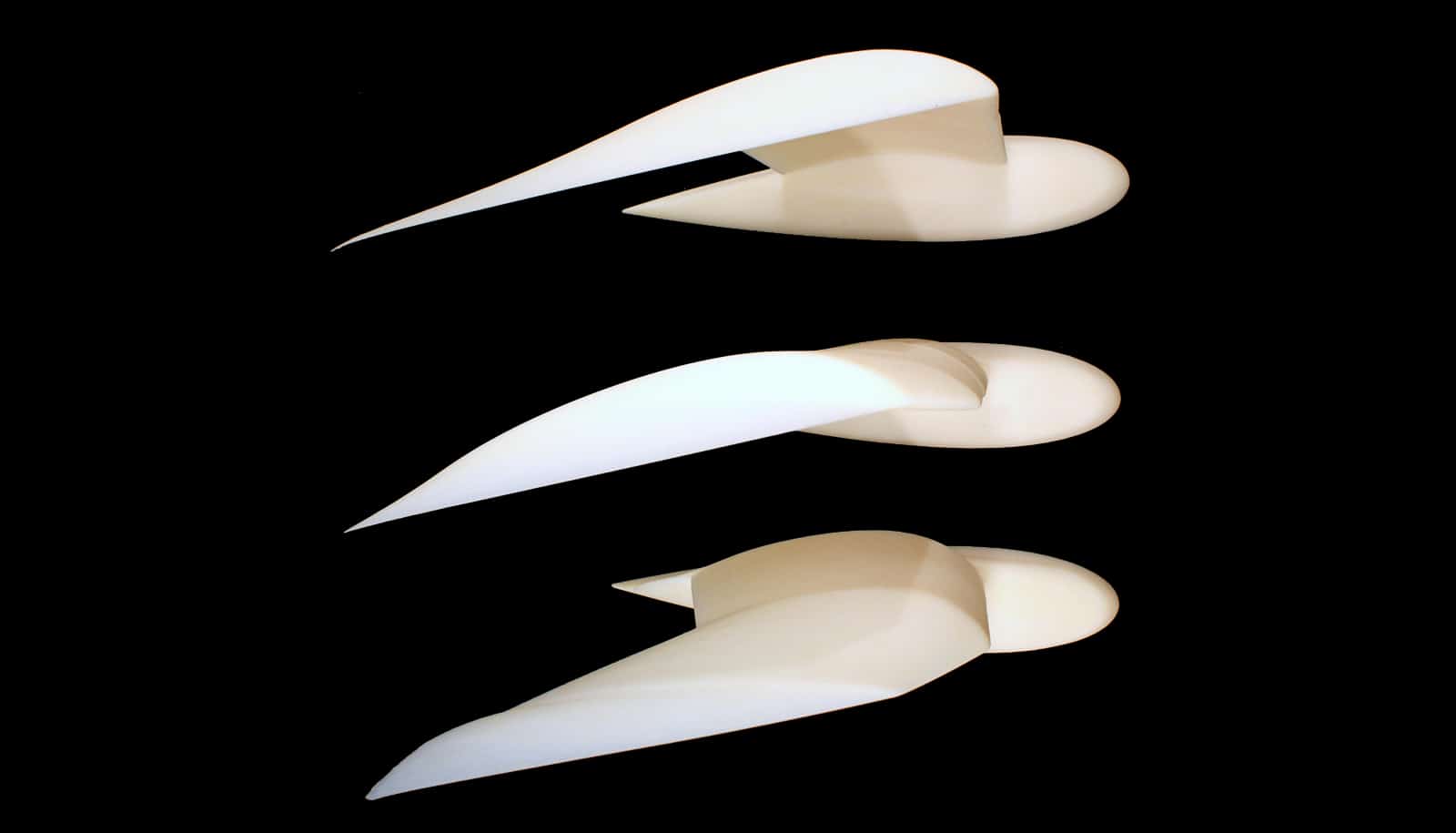

The best human drone pilots are very good at doing this and have so far always outperformed autonomous systems in drone racing. Now, the researchers have created an algorithm that can find the quickest trajectory to guide a quadrotor—a drone with four propellers—through a series of waypoints on a circuit.

“Our drone beat the fastest lap of two world-class human pilots on an experimental race track,” says Davide Scaramuzza, who heads the Robotics and Perception Group at University of Zurich and the Rescue Robotics Grand Challenge of the NCCR Robotics, which funded the research.

“The novelty of the algorithm is that it is the first to generate time-optimal trajectories that fully consider the drones’ limitations,” says Scaramuzza. Previous works relied on simplifications of either the quadrotor system or the description of the flight path, and thus they were sub-optimal.

“The key idea is, rather than assigning sections of the flight path to specific waypoints, that our algorithm just tells the drone to pass through all waypoints, but not how or when to do that,” adds Philipp Foehn, a PhD student and first author of the paper on the work.

The researchers had the algorithm and two human pilots fly the same quadrotor through a race circuit. They employed external cameras to precisely capture the motion of the drones and—in the case of the autonomous drone—to give real-time information to the algorithm on where the drone was at any moment.

To ensure a fair comparison, the human pilots were given the opportunity to train on the circuit before the race. But the algorithm won: all its laps were faster than the human ones, and the performance was more consistent. This is not surprising, because once the algorithm has found the best trajectory it can reproduce it faithfully many times, unlike human pilots.

Before commercial applications, the algorithm will need to become less computationally demanding, as it now takes up to an hour for the computer to calculate the time-optimal trajectory for the drone. Also, at the moment, the drone relies on external cameras to compute where it was at any moment. In future work, the scientists want to use onboard cameras. But the demonstration that an autonomous drone can in principle fly faster than human pilots is promising.

“This algorithm can have huge applications in package delivery with drones, inspection, search and rescue, and more,” says Scaramuzza.

The paper appears in Science Robotics.

Source: University of Zurich