Researchers have developed 3D-printed devices that can track and store their own use—without batteries or electronics.

Cheap and easily customizable, 3D-printed devices are perfect for assistive technology, like prosthetics or “smart” pill bottles that can help patients remember to take their daily medications. But these plastic parts don’t have electronics, which means they can’t monitor how patients are using them.

The new system uses a method called backscatter, through which a device can share information by reflecting signals that an antenna has transmitted to it.

“We’re interested in making accessible assistive technology with 3D printing, but we have no easy way to know how people are using it,” says coauthor Jennifer Mankoff, a professor in the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering at the University of Washington. “Could we come up with a circuitless solution that could be printed on consumer-grade, off-the-shelf printers and allow the device itself to collect information? That’s what we showed was possible in this paper.”

Previously the team developed the first 3D printed objects that connect to Wi-Fi without electronics. These purely plastic devices can measure if a detergent bottle is running low and then automatically order more online.

“Using plastic for these applications means you don’t have to worry about batteries running out or your device getting wet. That can transform the way we think of computing,” says senior author Shyam Gollakota, an associate professor in the Allen School. “But if we really want to transform 3D printed objects into smart objects, we need mechanisms to monitor and store data.”

The researchers tackled the monitoring problem first. In a previous study, their system tracks movement in one direction, which works well for monitoring laundry detergent levels or measuring wind or water speed. But now they needed to make objects that could monitor bidirectional motion like the opening and closing of a pill bottle.

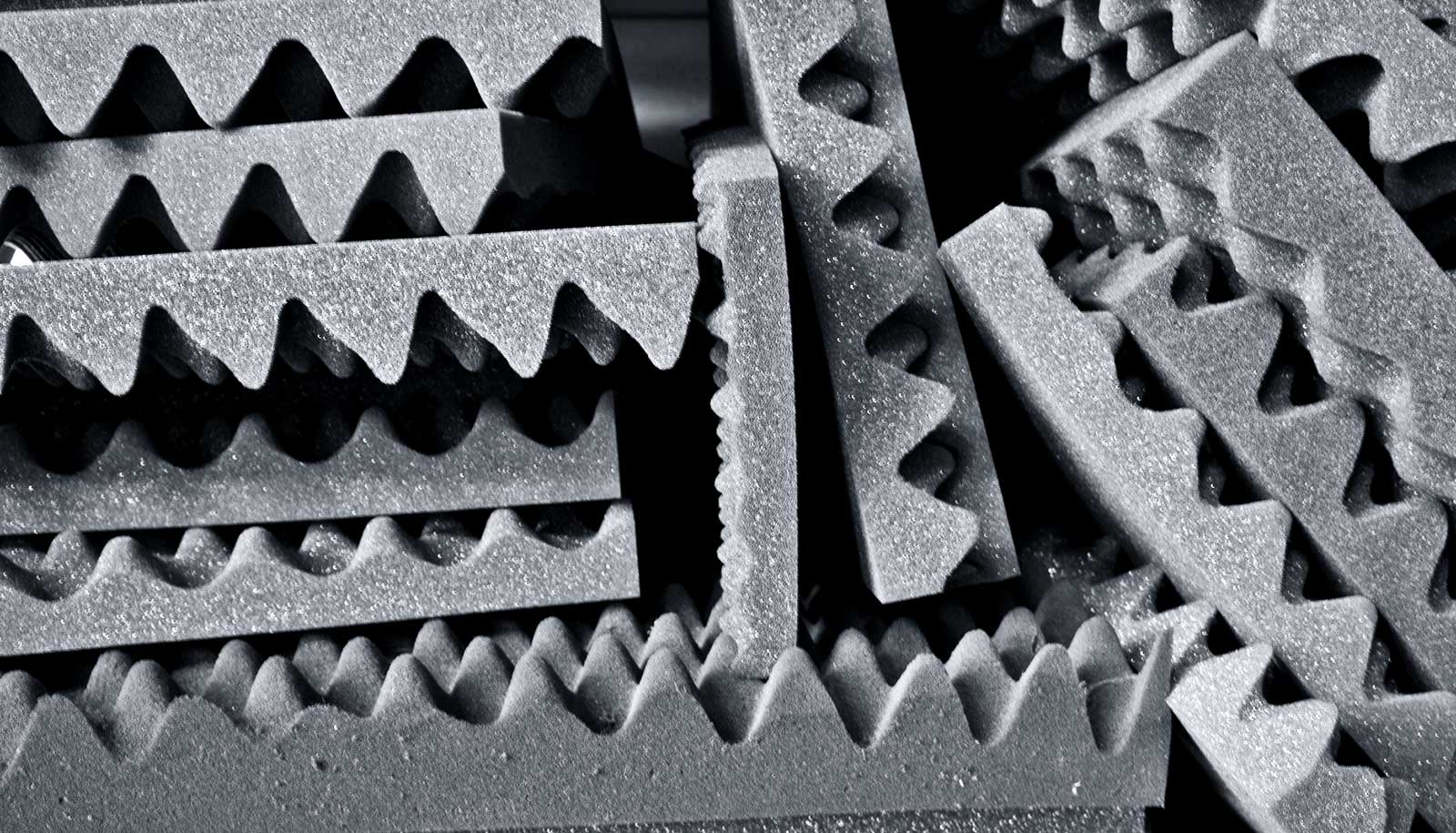

“Last time, we had a gear that turned in one direction. As liquid flowed through the gear, it would push a switch down to contact the antenna,” says lead author Vikram Iyer, a doctoral student in the UW Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering. “This time we have two antennas, one on top and one on bottom, that can be contacted by a switch attached to a gear. So opening a pill bottle cap moves the gear in one direction, which pushes the switch to contact one of the two antennas. And then closing the pill bottle cap turns the gear in the opposite direction, and the switch hits the other antenna.”

Movement is captured when the switch contacts one of the two antennas. Both of the antennas are identical, so the team had to devise a way to decode which direction the cap was moving.

“The gear’s teeth have a specific sequencing that encodes a message. It’s like Morse code,” says coauthor Justin Chan, a doctoral student in the Allen School. “So when you turn the cap in one direction, you see the message going forward. But when you turn the cap in the other direction, you get a reverse message.”

In addition to tracking, for example, pill bottle cap movement, this same method can monitor how people use prosthetics, such as 3D-printed e-NABLE arms. These mechanical hands, which attach at the wrist, help children with hand abnormalities grasp objects. When children flex their wrists, cables on the hand tighten to make the fingers close. So the team 3D printed an e-NABLE arm with a prototype of their bidirectional sensor that monitors the hand opening and closing by determining the angle of the wrist.

The researchers also wanted to create a 3D-printed object that could store its usage information while out of Wi-Fi range. For this application, they chose an insulin pen that could monitor its use and then signal when it was getting low.

“You can still take insulin even if you don’t have a Wi-Fi connection,” Gollakota says. “So we needed a mechanism that stores how many times you used it. Once you’re back in the range, you can upload that stored data into the cloud.”

This method requires a mechanical motion, like the pressing of a button, and stores that information by rolling up a spring inside a ratchet that can only move in one direction. Each time someone pushes the button, the spring gets tighter. It can’t unwind until the user releases the ratchet, hopefully when in range of the backscatter sensor. Then, as the spring unwinds, it moves a gear that triggers a switch to contact an antenna repeatedly as the gear turns. Each contact is counted to determine how many times the user pressed the button.

Each time someone pushes the button, a spring inside the ratchet gets tighter.

These devices are only prototypes to show that it is possible for 3D printed materials to sense bidirectional movement and store data. The next challenge will be to take these concepts and shrink them so that they can work in real pill bottles, prosthetics, or insulin pens, Mankoff says.

“This system will give us a higher-fidelity picture of what is going on,” she says. “For example, right now we don’t have a way of tracking if and how people are using e-NABLE hands. Ultimately what I’d like to do with these data is predict whether or not people are going to abandon a device based on how they’re using it.”

The team will present its findings at the ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology in Berlin.

The National Science Foundation and Google Faculty Awards funded the research.

Source: Sarah McQuate for University of Washington