The first national study of the bites and stings inflicted by Australia’s venomous creatures shatters stereotypes about which most threaten human health.

The 13 years of data reveal that bees and other insects—not snakes, spiders, or jellyfish—pose the biggest public health threat. Snakes, however, are the country’s deadliest venomous creatures.

“Australia has an international reputation for being the epicenter of all things venomous…”

“Australia has an international reputation for being the epicenter of all things venomous, whether it’s snakes and spiders on land, or lethal jellyfish, stingrays, stonefish, and octopi in our oceans,” says lead researcher Ronelle Welton, a public health expert with the Australian Venom Research Unit at the University of Melbourne’s department of pharmacology.

“Yet until now, there has been a real lack of data about where venomous injuries occur, the reasons why they happen, and what happens after a person is bitten.”

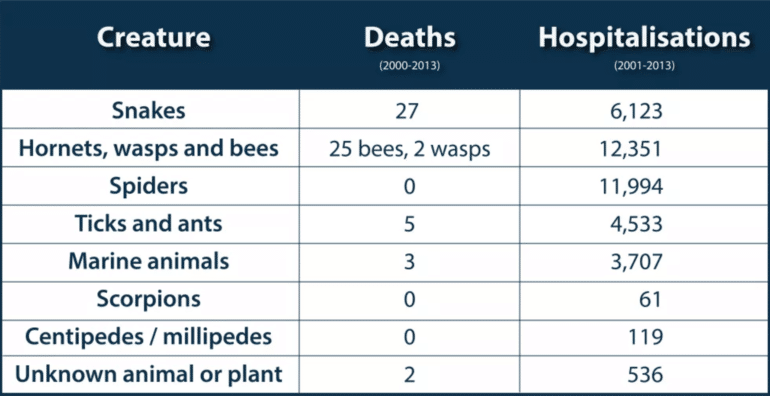

Including fatalities, venomous stings and bites resulted in almost 42,000 hospitalizations over the study period. Bees and wasps were responsible for just over one-third (33 percent) of hospital admissions, followed by spider bites (30 percent), and snake bites (15 percent).

In all, 64 people died from a venomous sting or bite, with over half of these (34) caused by an allergic reaction to an insect bite causing anaphylactic shock. Of these, 27 deaths were the result of a bee or wasp sting, with only one case of a beekeeper being killed.

But snakebites also caused 27 deaths. Snake bite envenoming caused nearly twice as many deaths per hospital admission than any other venomous creature.

Tick bites caused three deaths and ant bites another two. There were no spider bite fatalities. A man died from a red back spider bite in April 2016, the first spider bite death in more than 30 years, but it was outside the study period.

Surprisingly, over half of these deaths happened at home, and almost two-thirds (64 percent) occurred not in the isolated areas, but in major cities and inner-regional areas where healthcare is readily accessible.

These clingfish are venomous and nobody knew it

Welton and her colleagues examined hospital data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) and mortality data from National Coronial Information System from August 2001 to May 2013, as well as Cause of Death Unit Record Files collated by the AIHW. Their findings appear in the Internal Medicine Journal.

Blasé about bees

Researchers believe one of the reasons that anaphylaxis from insect stings has proven deadly may be because people are complacent in seeking medical attention and anaphylaxis can kill quickly.

“We need to understand why people are dying from bee sting anaphylaxis at home.”

While three-quarters of snakebite fatalities at least made it to hospital, only 44 percent of people who died from an allergic reaction to an insect sting got to the hospital.

“Bees are a ubiquitous creature that we are accustomed to seeing. Perhaps it’s because bees are so innocuous that most people don’t really fear them in the same way they fear snakes,” Welton says.

“Without having a previous history of allergy, you might get bitten and although nothing happens the first time, you’ve still developed an allergic sensitivity. We need to understand why people are dying from bee sting anaphylaxis at home.”

Professor Daniel Hoyer, who leads the University of Melbourne’s department of pharmacology and therapeutics, says it could be lack of access to adrenaline auto-injectors used to treat anaphylactic shock, also known as Epipens.

“The number one surprise in this research is there are so many bites from insects,” Hoyer says. “The majority of serious envenoming incidents involved anaphylactic shock. I suspect the incidence of allergy is enormous in this country.

“We observed this during the recent asthma storm, when over 8,500 patients showed up in the emergency room in hospitals around Melbourne and at least eight died, yet many of these people did not know about their susceptibility to strong allergic reactions or asthma status. We need to ask why don’t people at risk have Epipens at home?”

Horses are deadlier than snakes

Given there are 140 species of land snakes in Australia, snakebite fatalities are very rare, at 27 for the study period. To put that in perspective, 100,000 people die from snakebite globally each year.

While it’s natural to be frightened of snakes, Welton says a person is actually more likely to die from an encounter with a horse or a dog.

Since 2000, 74 people have died from being thrown or trampled by a horse. Twenty-six people have died from shark attack and 23 from altercations with dogs. Crocodiles have been responsible for 19 deaths.

And compared to 4,820 drowning deaths and 974 deaths from burns in the same period, the snakebite figures are still remarkably low.

Don’t try to kill the snake

Men aged 30 to 35-years-old are most likely to be bitten or stung, followed closely by the five to nine-year-old age group, which Hoyer says may reflect greater risk-taking behavior among men and boys.

“There is a massive discrepancy between men and women that starts very early,” Hoyer adds. “Even between the ages of zero and four-years, boys are suffering bites and stings more frequently than girls and this is across the age spectrum until 75 when it evens out.

“When you consider the highest age groups were between 25 and 45, we can assume risk taking-behavior is more common in men—it could be that blokey culture is driving it.”

Virus genome carries spider venom DNA

Welton says she was surprised to see a pattern of snake bites across the populous coastal areas of Australia.

“A snake bite is usually thought of as an outdoor medical emergency, but our data showed the majority of snake bite fatalities occur around a person’s residence within the major city or inner regional area,” Welton says.

“The big question is how can we manage this co-existence without being detrimental to people and the creatures themselves? For me, it comes down to understanding, education, prevention, and first-aid.

“Giving people advice to wear boots in the bush and make lots of noise to avoid snake bite isn’t good enough. It’s everyone’s responsibility to learn first aid, particularly pressure-immobilization, which can be applied for a range of injuries when it comes to animals.

“And don’t try to kill the snake. In numerous cases, that’s when people get bitten. Go to your council website, find a snake-catcher, put the number on your fridge. Make sure you’re prepared.”

Jellyfish safety

The study was limited to those deaths actually recorded as being caused by envenoming and Welton notes “the information reviewed was only as accurate as the information entered, and some records may not have made it into the national dataset.”

According to the data there were only three recorded marine stinger fatalities in the study, all of them box jellyfish.

Welton believes the public safety messaging around jellyfish management has been very effective.

“From a jellyfish perspective, there has been a huge public health intervention and yet for bees and snakes, not so much,” she says. “You have the tourism industry, the fisheries industry, surf lifesaving, all with a stake in jellyfish sting prevention who champion this need. Linking up these industries and health networks would help track cases, for example Irukandji stings have been recorded progressing down the Queensland coast for some years.”

“When you look at how comprehensive awareness campaigns are about jellyfish stings in certain parts of Australia, compared to bee sting anaphylaxis which can happen everywhere, the public health approach is certainly not as focused.”

Source: University of Melbourne