Scientists have invented a new biosensor technology, also called a “lab on a chip,” that could monitor your health and exposure to bacteria, viruses, and pollutants.

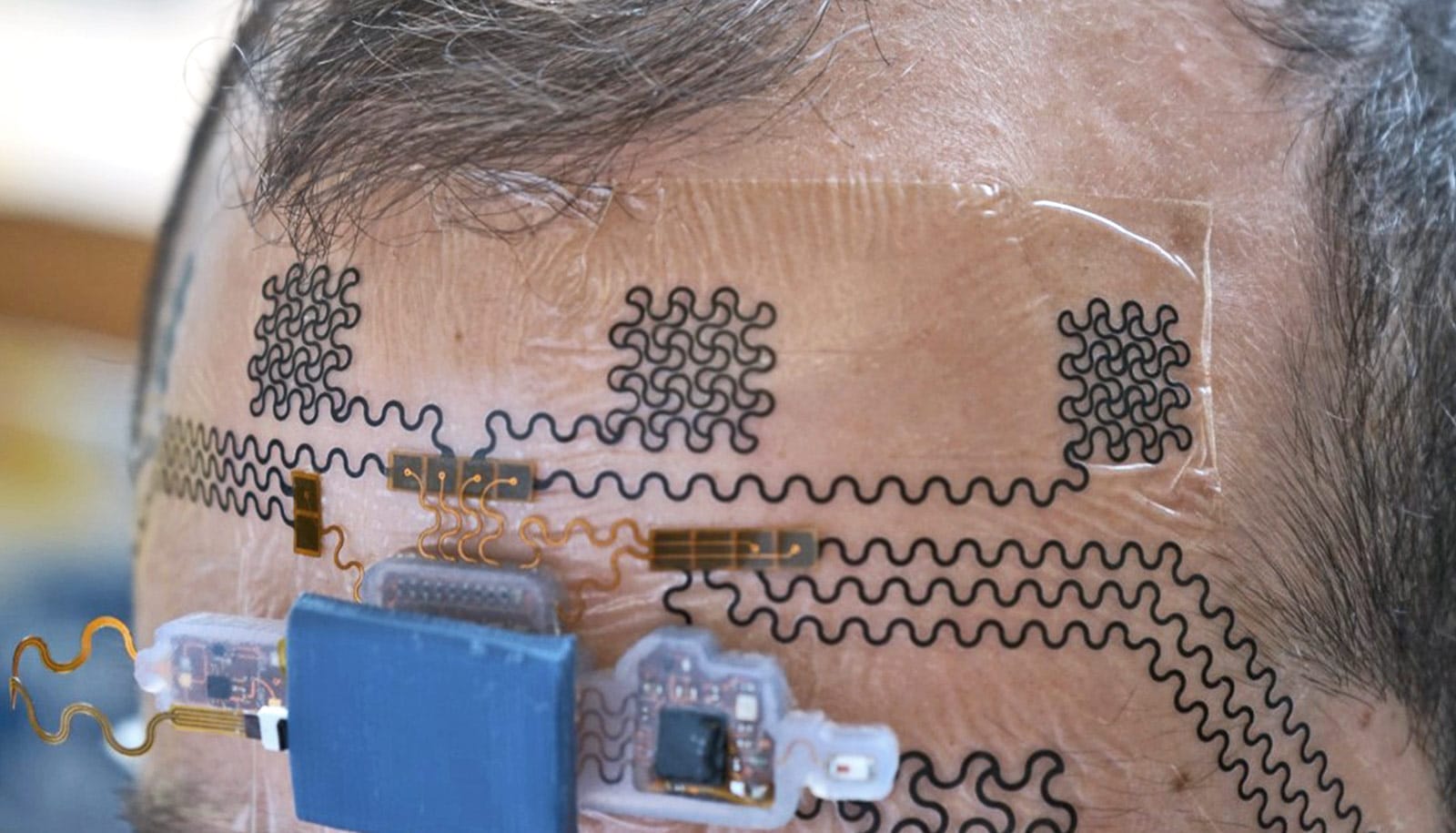

The technology is also small enough to fit into a hand-held or wearable device, the scientists share in a study based on their invention.

“Imagine ordering a salad at a restaurant and testing it for E. coli or Salmonella bacteria.”

“This is really important in the context of personalized medicine or personalized health monitoring,” says Mehdi Javanmard, an assistant professor in the electrical and computer engineering department at Rutgers University-New Brunswick.

“Our technology enables true labs on chips. We’re talking about platforms the size of a USB flash drive or something that can be integrated onto an Apple Watch, for example, or a Fitbit.”

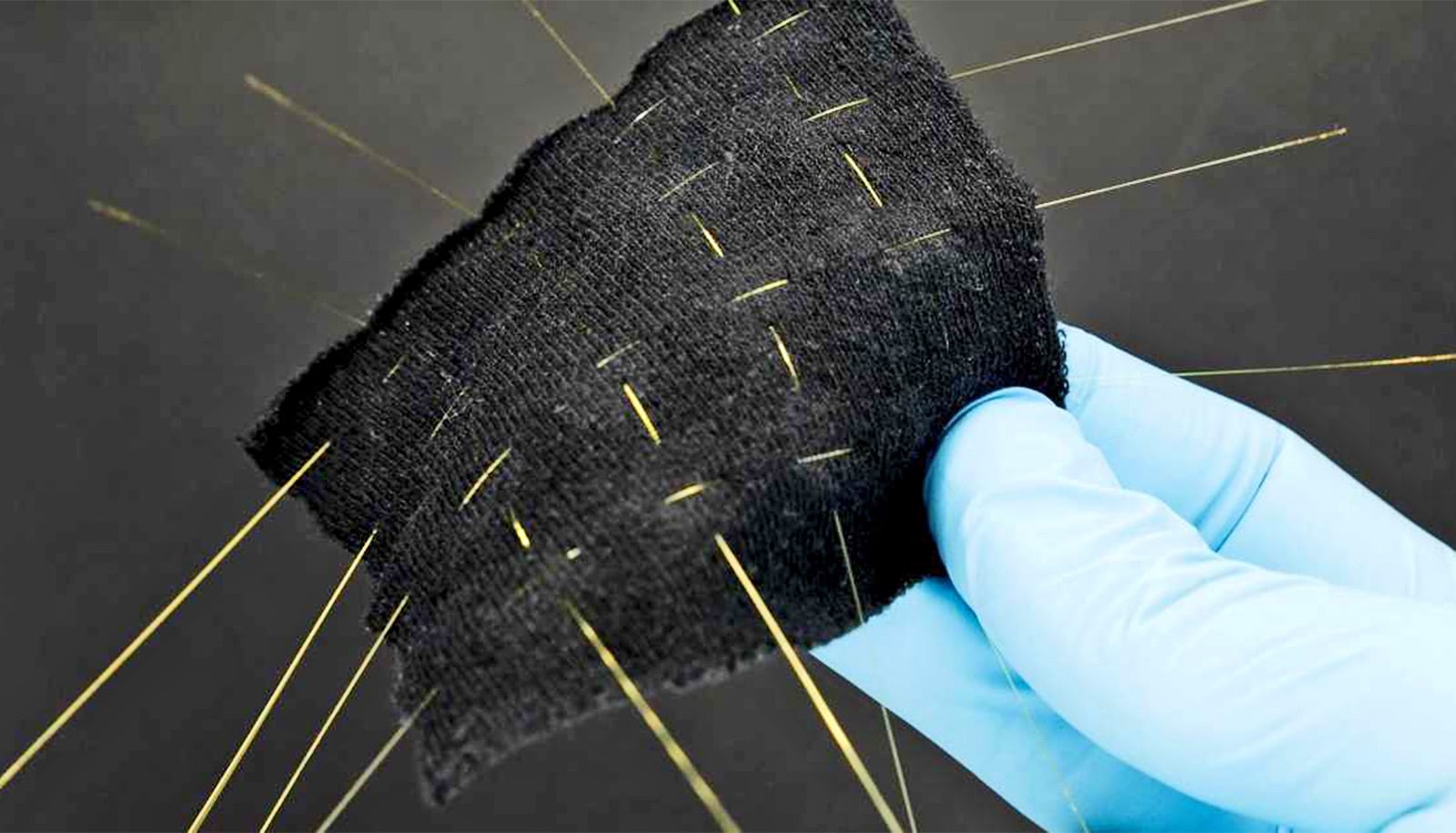

The technology, which involves electronically barcoding microparticles, giving them a bar code that identifies them, could be used to test for health and disease indicators, bacteria and viruses, along with air and other contaminants, says Javanmard, senior author of the study.

In recent decades, research on biomarkers—indicators of health and disease such as proteins or DNA molecules—has revealed the complex nature of the molecular mechanisms behind human disease. That has heightened the importance of testing bodily fluids for numerous biomarkers simultaneously, the study says.

“One biomarker is often insufficient to pinpoint a specific disease because of the heterogeneous nature of various types of diseases, such as heart disease, cancer, and inflammatory disease,” says Javanmard.

“To get an accurate diagnosis and accurate management of various health conditions, you need to be able to analyze multiple biomarkers at the same time.”

This ‘placenta on a chip’ mimics the real thing

Well-known biomarkers include the prostate-specific antigen (PSA), a protein generated by prostate gland cells. Men with prostate cancer often have elevated PSA levels, according to the National Cancer Institute. The human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) hormone, another common biomarker, is what home pregnancy test kits measure.

Bulky optical instruments are the state-of-the-art technology for detecting and measuring biomarkers, but they’re too big to wear or add to a portable device, Javanmard says.

Electronic detection of microparticles allows for ultra-compact instruments needed for wearable devices. The researchers’ technique for barcoding particles is, for the first time, fully electronic. That allows biosensors to be shrunken to the size of a wearable band or a micro-chip, the study says.

The technology is greater than 95 percent accurate in identifying biomarkers and fine-tuning is underway to make it 100 percent accurate, he says. Javanmard’s team is also working on portable detection of microrganisms, including disease-causing bacteria and viruses.

“Imagine a small tool that could analyze a swab sample of what’s on the doorknob of a bathroom or front door and detect influenza or a wide array of other virus particles,” he says. “Imagine ordering a salad at a restaurant and testing it for E. coli or Salmonella bacteria.”

‘Kidney on a chip’ could lead to precision drug dosing

That kind of tool could be commercially available within about two years, and health monitoring and diagnostic tools could be available within about five years, Javanmard says.

A study describing the invention recently appeared in the journal Lab on a Chip.

Source: Rutgers University