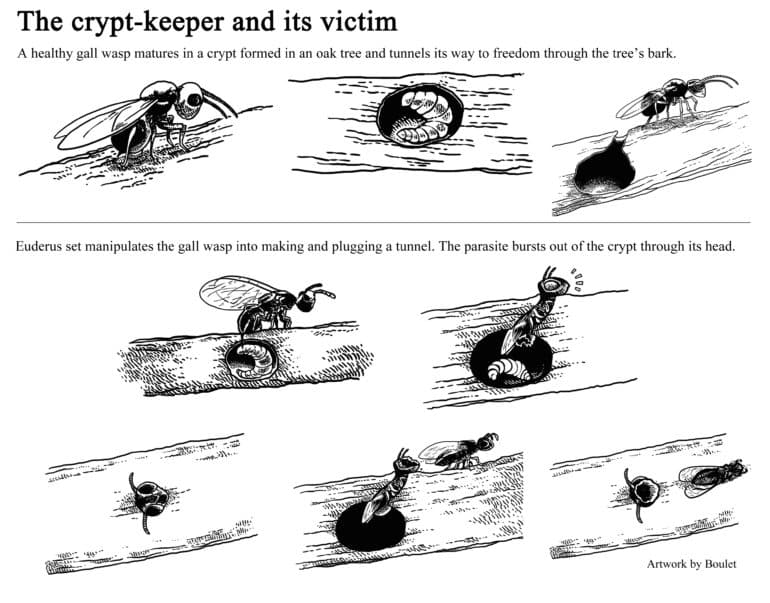

One kind of parasitic wasp, Euderus set, deposits its egg in the oak-tree home of another parasitic species—a gall wasp. The young E. set eventually chews its way to freedom, through its host’s head.

Rice University researchers nicknamed E. set the “crypt-keeper” wasp and say it’s a rare example of hypermanipulation, in which one parasite manipulates another.

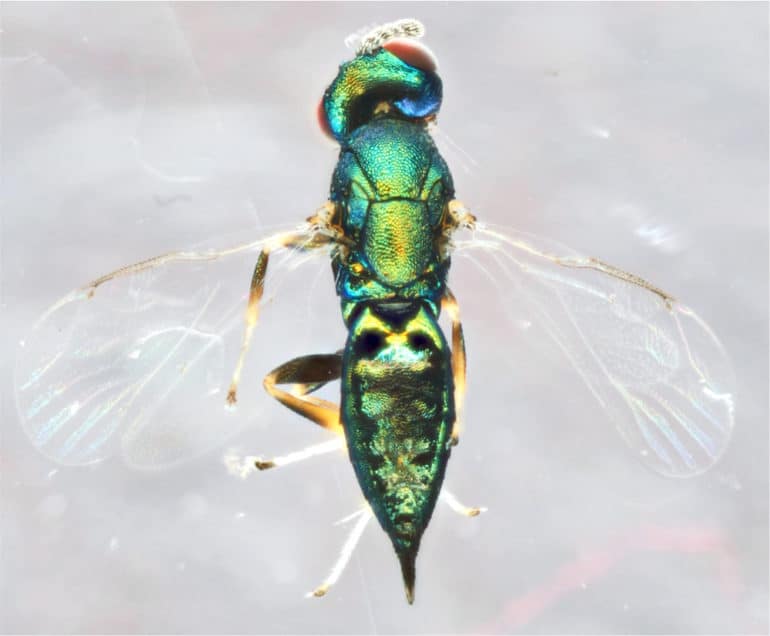

E. set and its gory emergence appear in two papers by evolutionary biologists Kelly Weinersmith and Scott Egan. The first paper, in the journal ZooKeys, describes the new wasp species in detail. The second, released in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, explains the species’ ghoulish strategy.

The discoverers named their wasp for Set, the Egyptian god of evil and chaos who trapped his brother Osiris in a crypt, killed him, and then cut him into little pieces.

When the wasp tries to escape, its head lodges in the hole. E. set can then consume the gall wasp’s internal organs and emerge, “Alien”-like, from its head case.

“It could be the parasitoid cues hosts to excavate early, but makes them do it less well than usual,” says Weinersmith, who studies parasites. “They only go part way and then they get stuck.

“That’s what I love about parasite manipulation of host behavior,” she says. “So many of the stories that have been uncovered are just as cool as the coolest science fiction movie.”

Egan originally discovered the wasp on the Gulf Coast of Florida in the summer of 2014 before finding it in trees at Rice and in an oak tree in his front yard. As part of this study, E. set has now been found in Georgia, Mississippi, and Louisiana.

“I was walking on a path through the sand dunes with my daughter that summer while on a family vacation and of course, I can’t not grab bugs everywhere I go,” says Egan about spotting a tree branch of interest. “It ended up being this rare cynipid (gall wasp) that I don’t see around here very often, and in a much higher density. Then I couldn’t stop myself.”

This fungus turns ants into ‘zombies’

Weinersmith first saw it while chatting with Egan during one of their initial meetings at Rice. “He had this cup of stuff on his desk,” she recalls. “Anytime Scott sees a gall, he cuts it off, sticks it in a cup, puts a coffee filter over it and waits to see what emerges.”

“A couple of weeks later, animals started coming out,” Egan says. “I did some dissections, shaved off the head with a razor blade, got into the wood, and in the belly of these beasts was another little tiny larva, sitting in the abdomen. I immediately called Kelly.”

The researchers hope to discover how E. set triggers the change in Bassettia’s behavior. “One hard thing is that we can’t see what’s happening until they come out,” Weinersmith says. “We’re talking to people to see if we can CAT scan the branches in various stages.”

But they already know how badly E. set needs its host. To see how well it could tunnel, they taped thin strips of bark over the dead heads and waited. The experiments showed the crypt-keeper was about three times more likely to die in the crypt if it had to dig through the head case and the bark.

Because close to 600 species in the Eulophid family are found in North America, and many attack or serve as biocontrol agents for agricultural pests, the researchers would also like to know if E. set’s manipulations are more common.

“Euderus set represents one of many millions of undescribed parasitic wasps with peculiar lifecycles,” says Andrew Forbes, a coauthor of both papers. His lab at the University of Iowa studies the evolution of parasitoid wasps, which he described as one of the most species-rich groups of animals on the planet.

Weinersmith notes the gall wasp victim is hardly unknown. Literally millions of specimens are in the possession of the American Museum of Natural History, most brought there by the entomologist Alfred Kinsey, who later earned renown for his human sexuality research.

“Scott was going through some of those museum samples and saw this phenomenon in those branches,” she says. “So it’s been in museums for years, there for people to see. But we couldn’t find any evidence that other people noticed this phenomenon and thought, ‘Maybe something weird is happening here.'”

Rice University, through the Huxley Faculty Fellowship in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and the BioSciences Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Undergraduate Fellowship, funded the research.

Source: Rice University