Sexual selection can take place after mating, not just before. New research suggests that it can have a surprisingly large impact on evolution.

Just as a male with a flashier tail might be more likely to win a mate, sperm that are more resilient or stronger swimmers could be more likely to successfully fertilize an egg. Over time, this selection can shape the process of evolution, as genes that make sperm more competitive are preferentially passed on.

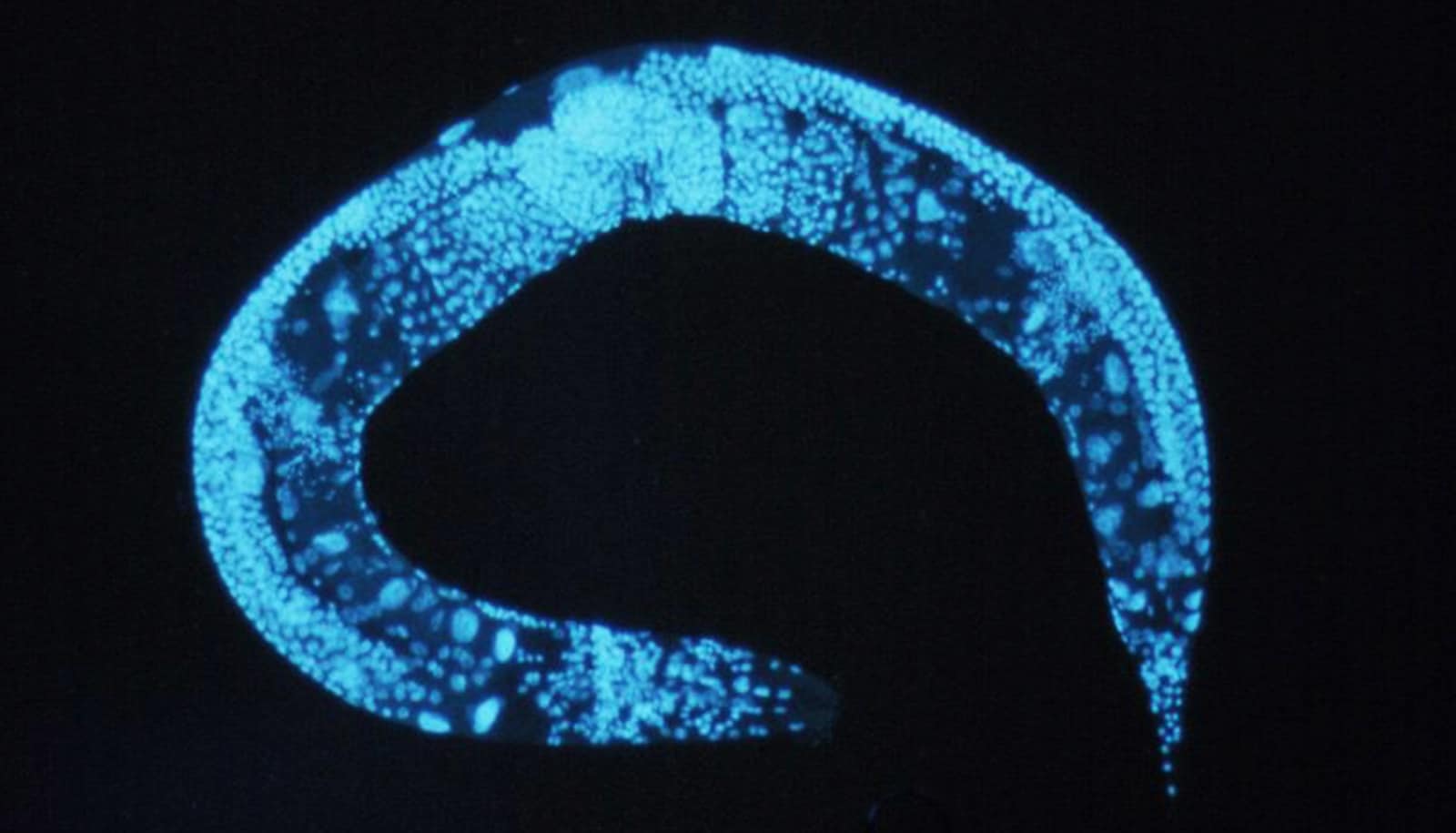

In lab experiments that followed Caenorhabditis elegans worms for many generations, sexual selection after sperm are released was a bigger driver of evolutionary change than sexual selection before mating. Researchers in the lab of University of Oregon biologist and provost Patrick Phillips report their findings in the journal PLOS Genetics.

Thanks to recent advances in gene-editing technology, “we were able to develop a genetic tool that gives us very fine temporal control—we can turn sperm production on and off in worms,” says Katja Kasimatis, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Toronto who led the research as part of her doctoral work at the University of Oregon.

That made it possible to tease apart the relative contributions of sexual selection before mating and after insemination.

“It’s something we haven’t been able to do before,” Kasimatis says. “It’s really hard to isolate what’s happening post-insemination.”

She and her colleagues followed the worms for 30 generations. (A perk of doing research with worms: The animals go from birth to reproductive age in about 3.5 days.) They introduced new competition at different points, either before or after mating took place, by manipulating when the worms produced sperm.

Increased competition before mating—adding worms with different genetics to the mating pool—decreased selection and slowed the rate of evolutionary change, the team found.

But more competing sperm enhanced selection and increased the rate of evolutionary change. Over 30 generations, males’ reproductive success increased by five to sevenfold.

The team also identified about 60 genes that showed rapid change over the course of the experiment. Those genes probably contribute to reproductive success in some way, but more than half of them haven’t yet been studied in detail.

“It suggests we have a lot of work to do,” Kasimatis says.

Source: Laurel Hamers for University of Oregon