A new tool and technique uses “vortex ultrasound,” a sort of ultrasonic tornado, to break down blood clots in the brain.

The approach worked more quickly than existing techniques to eliminate clots formed in an in vitro model of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST), according to a new study.

“Our previous work looked at various techniques that use ultrasound to eliminate blood clots using what are essentially forward-facing waves,” says Xiaoning Jiang, co-corresponding author of the paper in the journal Research. “Our new work uses vortex ultrasound, where the ultrasound waves have a helical wavefront.

“In other words, the ultrasound is swirling as it moves forward,” says Jiang, professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at North Carolina State University. “Based on our in vitro testing, this approach eliminates blood clots more quickly than existing techniques, largely because of the shear stress induced by the vortex wave.”

“The fact that our new technique works quickly is important, because CVST clots increase pressure on blood vessels in the brain,” says Chengzhi Shi, co-corresponding author and an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at Georgia Institute of Technology. “This increases the risk of a hemorrhage in the brain, which can be catastrophic for patients.

“Existing techniques rely in large part on interventions that dissolve the blood clot. But this is a time-consuming process. Our approach has the potential to address these clots more quickly, reducing risk for patients.”

CVST occurs when a blood clot forms in the veins responsible for draining blood from the brain. Incidence rates of CVST were between 2 and 3 per 100,000 in the United States in 2018 and 2019, and the incidence rate appears to be increasing.

“Another reason our work here is important is that current treatments for CVST fail in 20-40% of cases,” Jiang says.

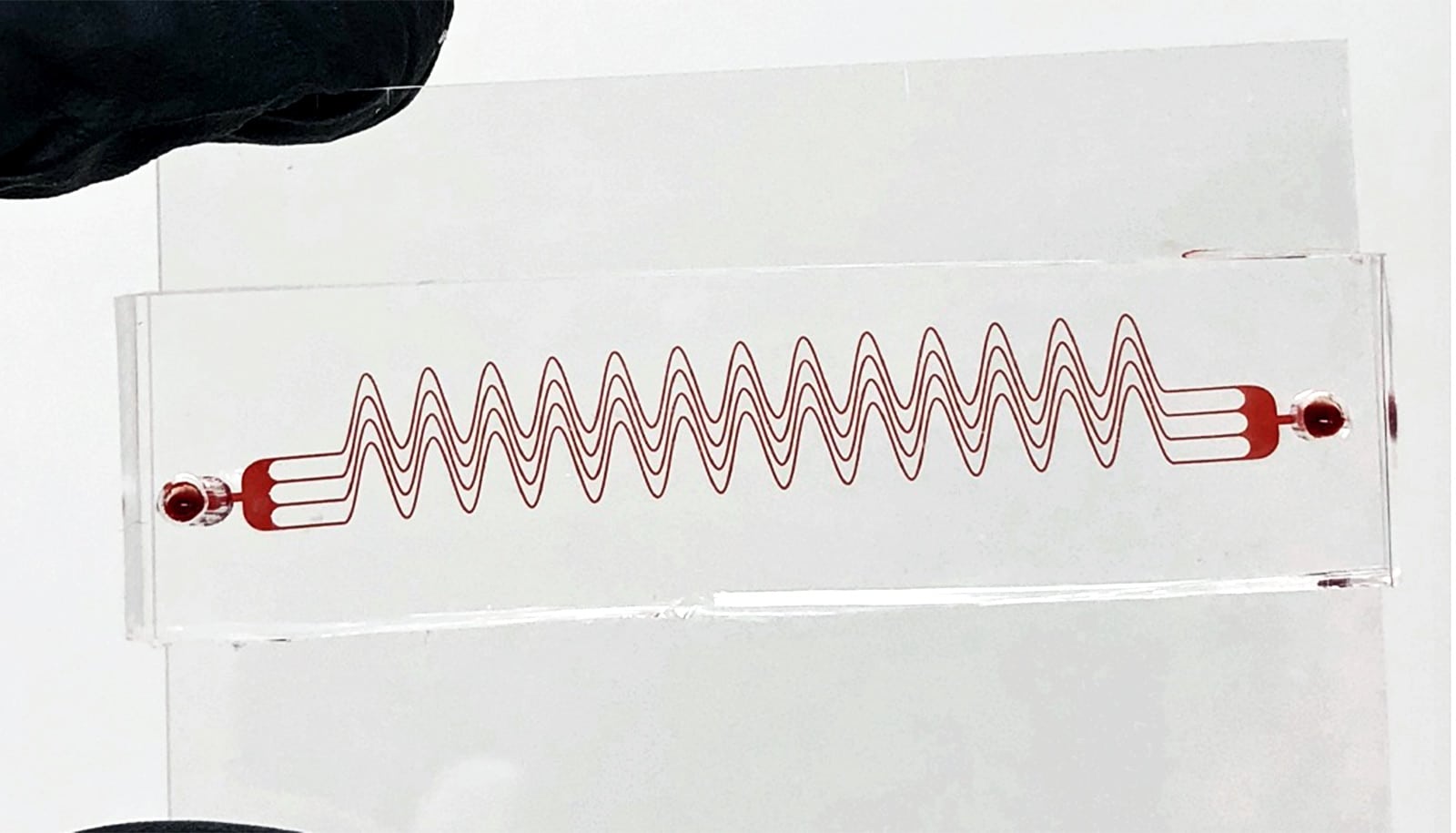

The new tool consists of a single transducer that is specifically designed to produce the swirling, vortex effect. The transducer is small enough to be incorporated into a catheter, which is then fed through the circulatory system to the site of the blood clot.

For proof-of-concept in vitro testing, the researchers used cow blood in a 3D-printed model of the cerebral venous sinus.

“Based on available data, pharmaceutical interventions to dissolve CVST blood clots take at least 15 hours, and average around 29 hours,” Shi says. “During in vitro testing, we were able to dissolve an acute blood clot in well under half an hour.”

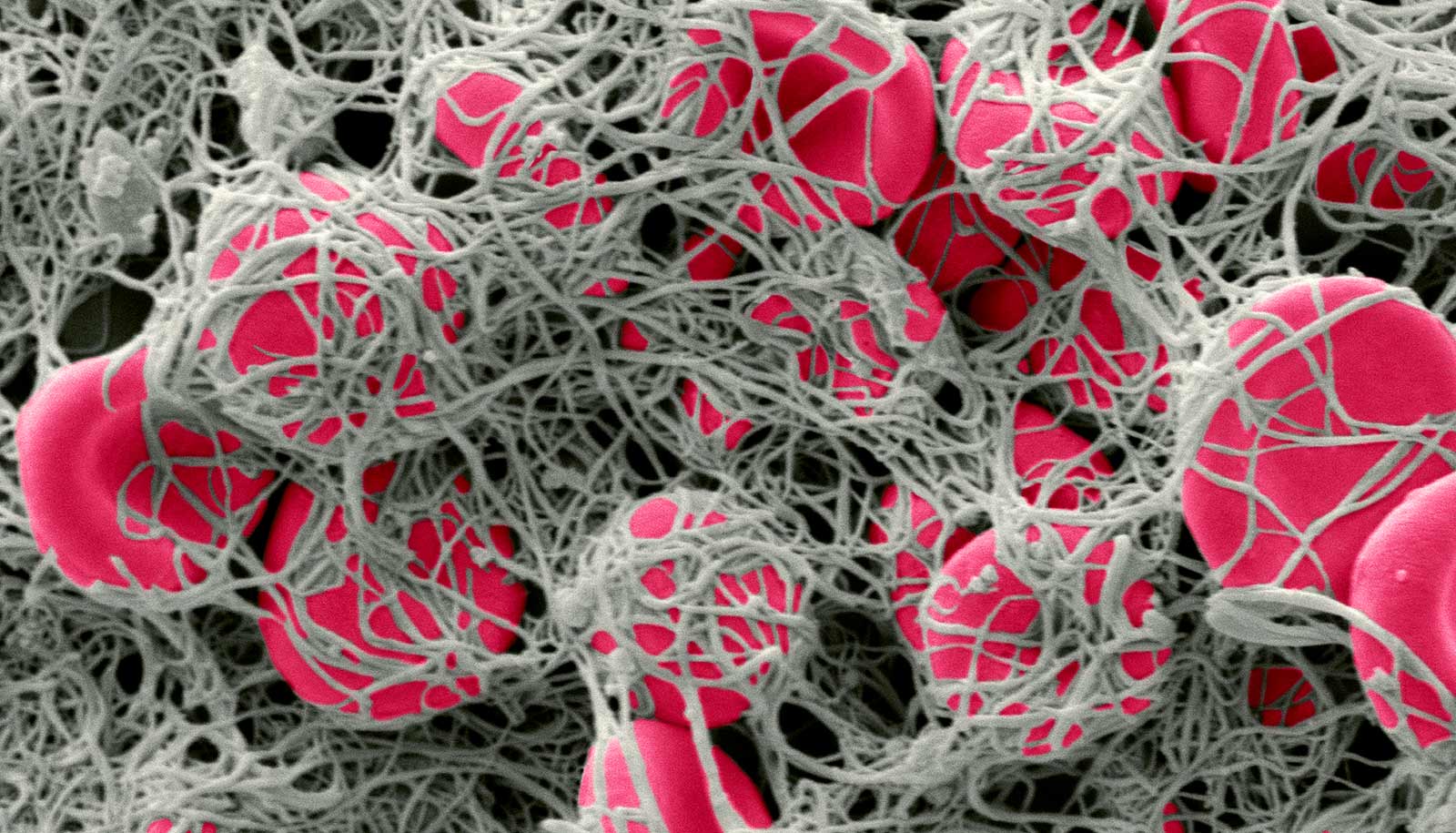

During any catheterization or surgical intervention there is a potential risk of harm, such as damaging the blood vessel itself. To address this issue, the researchers performed experiments applying vortex ultrasound to animal blood vein samples. Those tests found no damage to the walls of the blood vessels.

The researchers also conducted tests to determine whether the vortex ultrasound caused significant damage to red blood cells. They found that there was not substantial damage to red blood cells.

“The next step is for us to perform tests using an animal model to better establish the viability of this technique for CVST treatment,” Jiang says. “If those tests are successful, we hope to pursue clinical trials.”

“And if the vortex ultrasound ever becomes a clinical application, it would likely be comparable in cost to other interventions used to treat CVST,” says Shi.

Bohua Zhang, a PhD student, Huaiyu Wu, a postdoctoral researcher, both at NC State, and Howuk Kim, a former PhD student at NC State now on faculty at Inha University, are co-lead authors of the paper. Additional coauthors are from Georgia Tech, the University of Michigan, the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, UNC Chapel Hill, and NC State.

The National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation funded the work.

Source: NC State