Nerve transfer surgery for people suffering tetraplegia after a traumatic spinal cord injury can improve independence, according to new research.

Mary Galea AM, a professorial fellow at the University of Melbourne and Royal Melbourne Hospital, and Natasha van Zyl, a plastic and reconstructive surgeon at Austin Health, explain their research here:

Spinal cord injury is a devastating, life-changing injury.

Every year between 250,000 and 500,000 people worldwide suffer a spinal cord injury, with just over 50 percent resulting in tetraplegia that results in some degree of paralysis in all four limbs—the legs and arms.

Loss of upper limb function affects almost every aspect of a person’s work, family, and social life. Regaining some form of arm and hand function is the highest priority for people with tetraplegia.

Traditionally, some arm and hand functions have been reconstructed using tendon transfers, which move the tendon of a functioning muscle, like one of the elbow flexors, to a new site to recreate the function of a paralyzed wrist extensor.

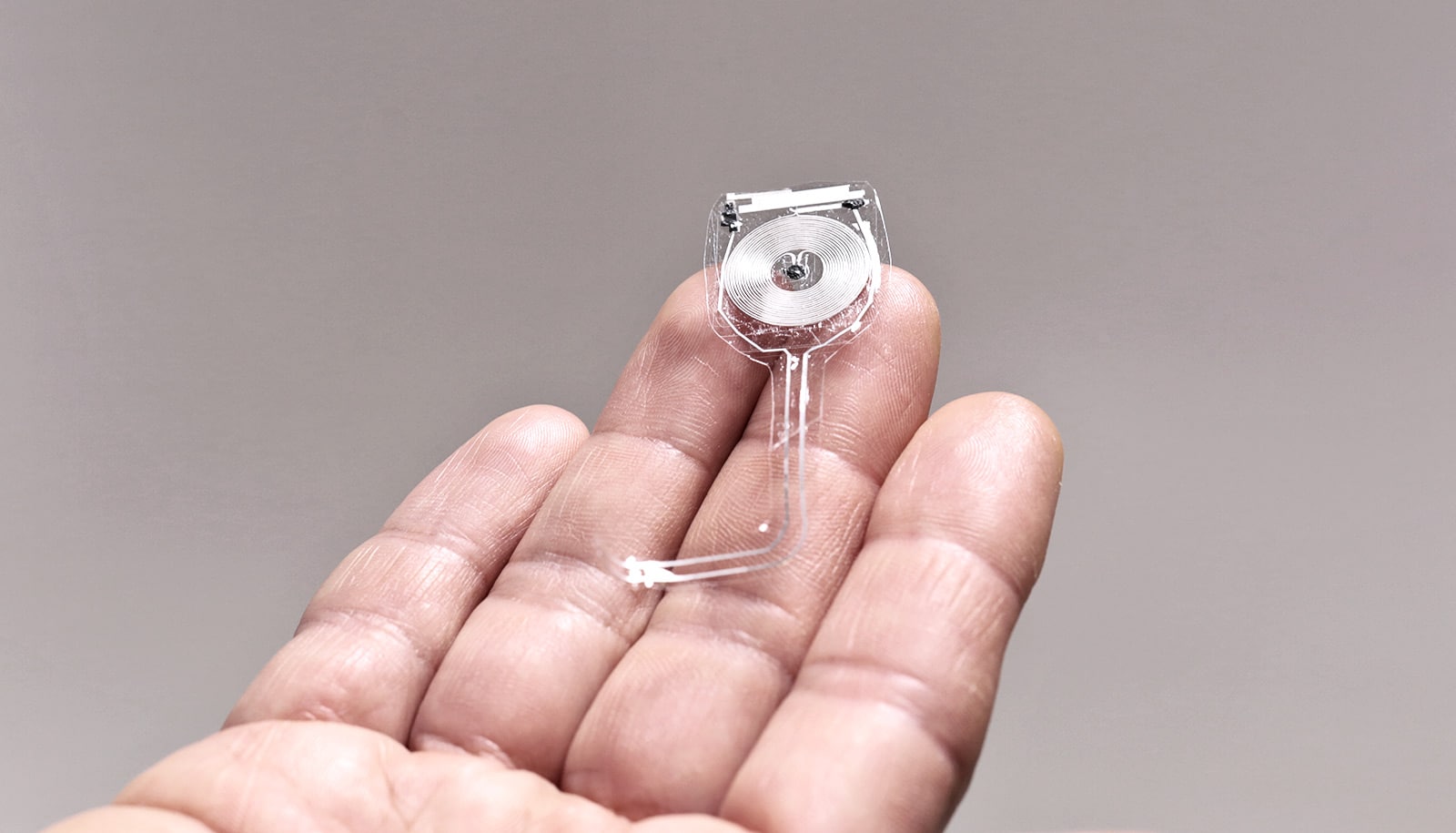

But nerve transfers allow for direct surgical reanimation of the muscle that is anatomically and biomechanically designed to perform that function.

How does it work?

The process involves taking working nerves to expendable muscles, like one of the muscles that rotates the forearm, which hasn’t been affected by the spinal injury and attaching them to the nerves of paralyzed muscles below the injury; this can restore voluntary control and reanimate more than one paralyzed muscle.

For example, to restore grasp and pinch, the nerve to a spare functioning wrist muscle can be transferred to the nerve controlling thumb and finger flexion.

Our research group, which brought together the medicine department at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, and the plastic and reconstructive surgery department and the Victorian Spinal Cord Service at Austin Health, just published the largest to date prospective, consecutive case series of nerve transfers undertaken at a single center in the tetraplegic population in the medical journal The Lancet.

A case series is a group or series of case reports involving consecutive patients who were given similar treatment.

The sixteen patients—13 male and three female—with average age of 27 years and within 18 months of traumatic spinal cord injury affecting the mid-cervical region (or the neck), were recruited from people referred to Austin Health for assessment in the Upper Limb Clinic.

Most of the injuries were the result of motor vehicle accidents or sports injuries.

Participants underwent single or multiple nerve transfers in one or both upper limbs to restore elbow extension, grasp, pinch, and hand opening.

In ten participants, nerve transfers were performed in one hand to restore grasp and pinch while tendon transfers were performed on the other.

We then looked at the clinical and functional outcomes of 59 nerve transfer procedures in 27 limbs.

Daily activity boost for people with tetraplegia

The people involved completed assessments of their level of independence related to activities of daily living—like self-care, going to the toilet, their upper limb function, muscle power, grasp and pinch strength, as well as hand opening ability—before surgery, one year after surgery, and again two years later.

At the two-year point, we found significant improvements in their independence, and ability to pick up and release objects of different sizes within a specified time.

Prior to surgery, none of the participants were able to perform the grasp or pinch strength tests, but two years later, their pinch and grasp strength was sufficient to allow them to do most activities of daily living.

The outcomes in hands where grasp and pinch had been reconstructed with nerve transfers were similar to those reconstructed with tendon transfers.

But a hand reconstructed with a nerve transfer for grasp and pinch had a more natural appearance and feel for social interactions and opened more easily for use of electronic devices. It meant the patients were satisfied, would have the surgery again and would recommend it to others.

There were four failed nerve transfers in three participants, who later underwent tendon transfer to improve hand function.

There were minor adverse side effects including a change in sensation and a temporary reduction in wrist strength which had resolved by the 12-month assessment. But, there were no serious adverse reactions related to the surgery.

Long-term follow up of nerve transfer surgery is highly desirable and funding to establish a registry is being sought to examine the effects of nerve transfer surgery over time.

Nerve transfer surgery is a safe and effective addition to the surgical techniques available for upper limb reanimation for people with tetraplegia and should be offered to eligible patients.

It can mean a significant improvement in independence after a traumatic and life-changing injury.

Source: University of Melbourne