Dysfunction involving an unusual type of thymocyte cell found in small amounts in every person may be why some people develop T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, research finds.

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, or T-ALL, affects more than 6,000 Americans each year.

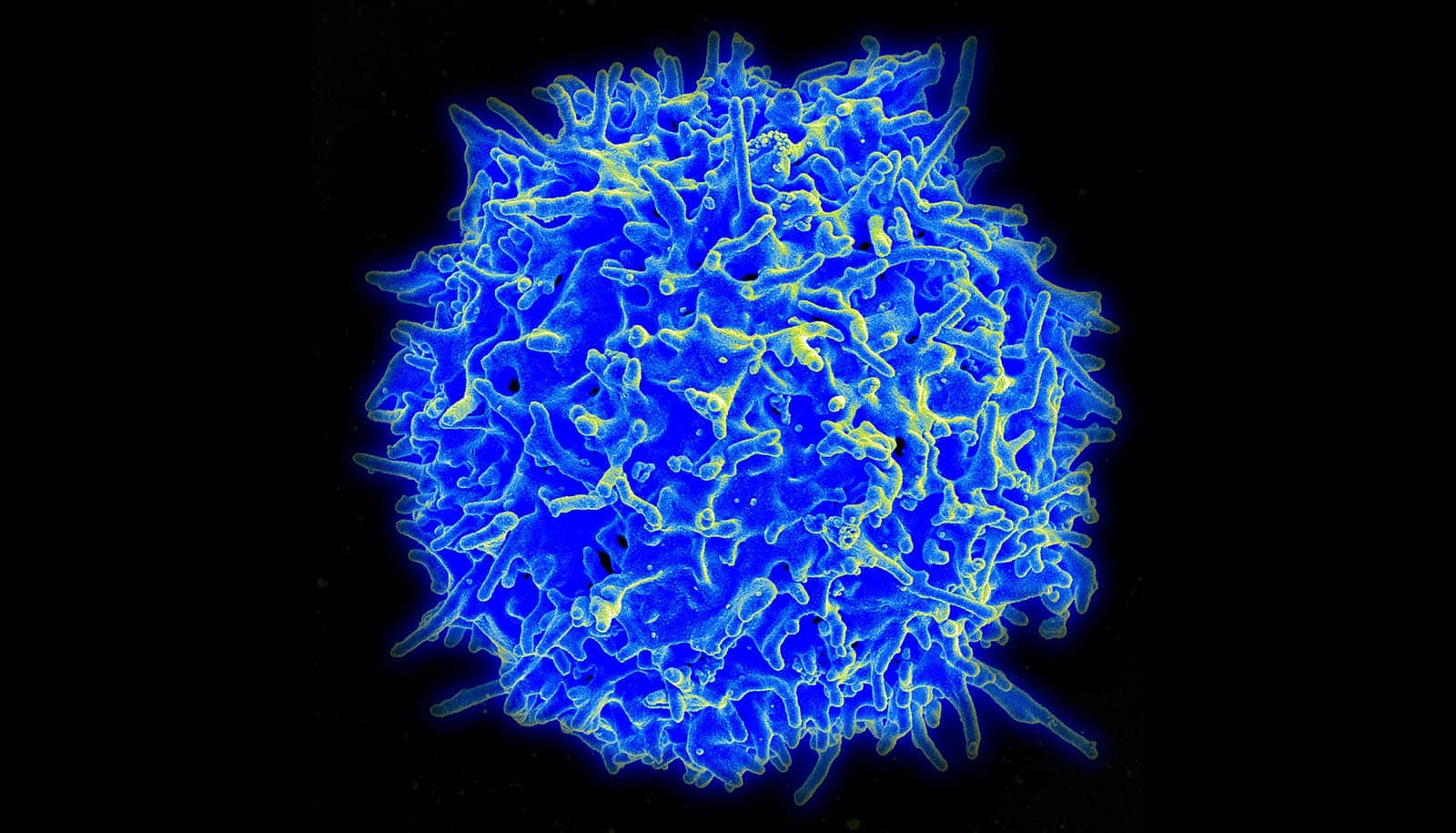

Researchers characterized the thymocyte cells—an immune cell present in the thymus—while studying mice with T-ALL. They determined all of the rodent tumors originated from the same type of T cell that expresses a unique set of molecular markers.

“Once we identified the cell in mice, we wondered if humans have that same cell type and in the same quantity,” says senior author Adam Schrum, associate professor of bioengineering, molecular microbiology and immunology, and surgery at the University of Missouri School of Medicine and College of Engineering.

“The human samples we obtained contained the same T cells and in the exact quantity found in mice.”

That rare cell, which makes up just 0.01% of all cells in the thymus gland, became known as “EADN.” Schrum’s team next wanted to know if every human T-ALL case originated from EADN.

“Over a three-year period, we examined five T-ALL cases at University of Missouri Health Care,” Schrum says. “We looked at cell samples from each patient and discovered one of those five cases seems to have originated from an EADN cell. We’re not saying that EADN is the only cell that causes this type of cancer, but our findings show it is responsible for some cases. This is a very exciting discovery.”

Schrum’s team also found something else unique about EADN cells. A molecule called major histocompatibility complex (MHC), which drives autoimmunity and other immune responses, is what signals EADN cells to turn into cancer in mice.

“It’s like an auto-immune reaction that causes EADN to turn into cancer,” Schrum says. “Many other cells in the thymus cannot do this. Now that we’ve determined the signals required for this transformation, this discovery could point to potential strategies to treat it.”

Schrum says the next step is to determine how frequently human T-ALL cases originate from EADN cells, in hopes of learning how to better personalize treatments for each person’s unique cancer case.

The study appears in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

Source: University of Missouri