Researchers have made an unexpected stem cell discovery that could lead to new treatments for placenta complications during pregnancy.

It’s possible to reprogram adult skin cells into cells similar to human embryonic stem cells that can then be used to develop tissue from human organs, but the same process can’t yet create placenta tissue.

These stem cells, called induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), opened up the potential for personalized cell therapies and new opportunities for regenerative medicine, safe drug testing, and toxicity assessments, but little has been known about exactly how they were made.

A team, led by professor Jose Polo of Monash University’s Biomedicine Discovery Institute and the Australian Research Medicine Institute, and assistant professor Owen Rackham of Duke-NUS, examined the molecular changes the adult skin cells went through to become iPSCs.

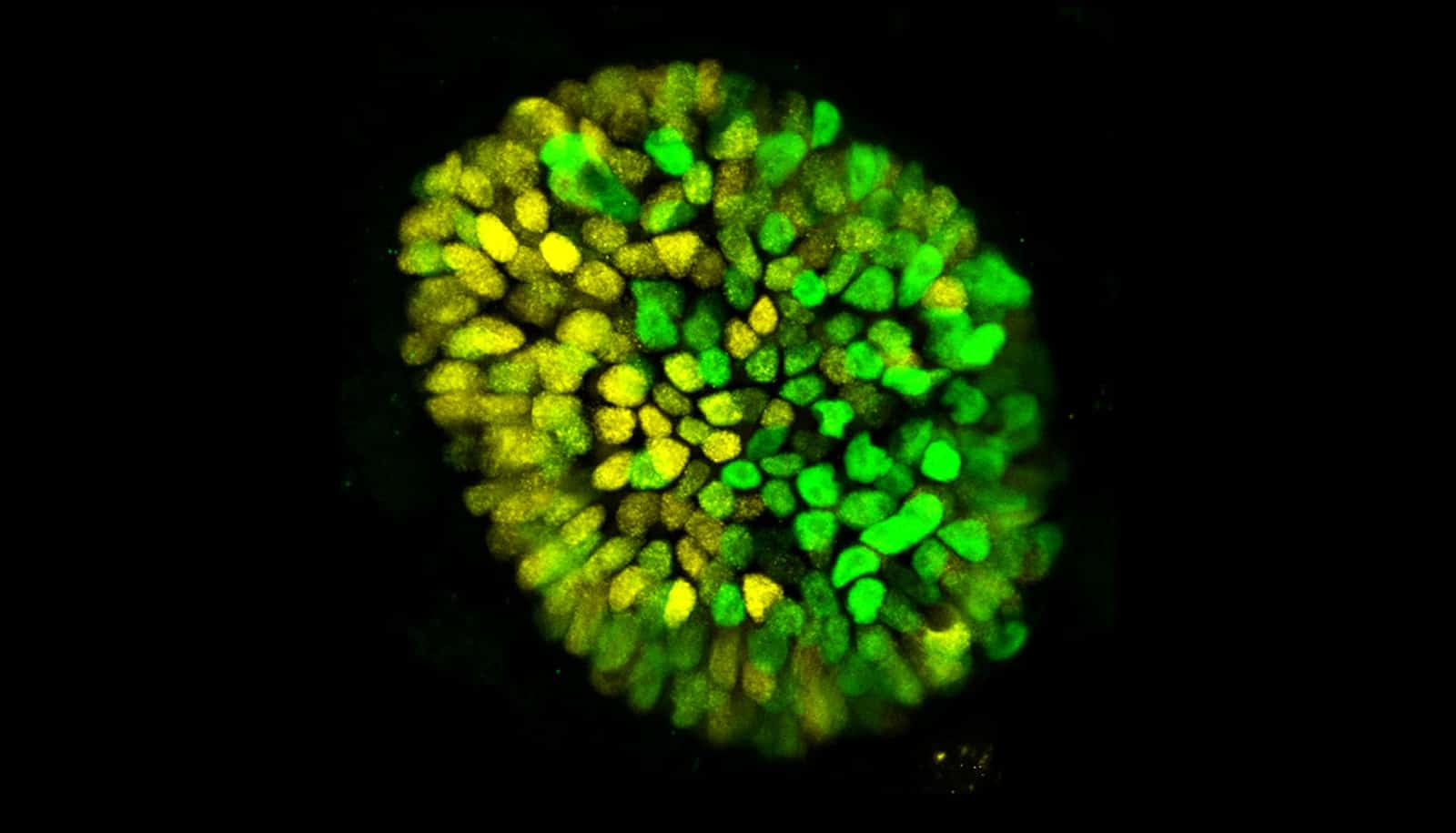

It was during the study of this process that they discovered a new way to create induced trophoblast stem cells (iTSCs) that can be used to make placenta cells.

The discovery will enable further research into new treatments for placenta complications and the measurement of drug toxicity to placenta cells, which has implications during pregnancy.

“This is really important because iPSCs cannot give rise to placenta, thus all the advances in disease modeling and cell therapy that iPSCs have brought about did not translate to the placenta,” says Polo.

“When I started my PhD five years ago our goal was to understand the nuts and bolts of how iPSCs are made, however along the way we also discovered how to make iTSCs,” says co-first author of the paper Xiaodong Liu.

“This discovery will provide the capacity to model human placenta in vitro and enable a pathway to future cell therapies,” adds co-first author John Ouyang.

The study appears in Nature. The third first author is Fernando Rossello.

Source: Duke-NUS