A stem cell treatment for heart failure has shown promising results in preclinical trials, researchers report.

These cells, when transplanted into an injured heart, are able to repair damaged tissue and improve heart function, according to the study published in the journal npj Regenerative Medicine.

The most common cause of death worldwide is ischemic heart disease, which is caused by diminished blood flow to the heart. When blood flow to the heart is blocked, the heart muscle cells die—a condition called myocardial infarction or heart attack.

In this study, the researchers used a unique new protocol where they cultivated pluripotent, or immature, stem cells in the laboratory to grow into heart muscle precursor cells, which can develop into various types of heart cells. This is done through cell differentiation, a process by which dividing cells gain specialized functions. During preclinical trials, the precursor cells were injected into the area of the heart damaged by myocardial infarction, where they were able to grow into new heart muscle cells, restoring damaged tissue and improving heart function.

“As early as four weeks after the injection, there was rapid engraftment, which means the body is accepting the transplanted stem cells. We also observed the growth of new heart tissue and an increase in functional development, suggesting that our protocol has the potential to be developed into an effective and safe means for cell therapy,” says Lynn Yap, an assistant professor at Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. As the study’s first author, Yap led the research while she was an assistant professor with Duke-NUS’ Cardiovascular & Metabolic Disorders (CVMD) Programme.

In studies conducted by other groups, the transplantation of heart muscle cells that were already beating, brought about fatal side effects—namely, ventricular arrhythmia—abnormal heartbeats that can limit or stop the heart from supplying blood to the body.

The new procedure involves transplanting non-beating heart cells into the damaged heart. After the transplantation, the cells expanded and acquired the rhythm of the rest of the heart. With this procedure, the incidence of arrhythmia was cut by half. Even when the condition was detected, most episodes were temporary and self-resolved in around 30 days. In addition, the transplanted cells did not trigger tumor formation—another common concern when it comes to stem cell therapies.

“Our technology brings us a step closer to offering a new treatment for heart failure patients, who would otherwise live with diseased hearts and have slim chances of recovery. It will also have a major impact in the field of regenerative cardiology, by offering a tried-and-tested protocol that can restore damaged heart muscles while reducing the risk of adverse side effects,” says Karl Tryggvason, a professor with the Duke-NUS’ CVMD Programme and the senior author of the study.

Tryggvason, who is also a professor in diabetes research, is leading other studies to adapt this regenerative medicine method for patients with diabetes, macular degeneration in the eyes and those needing skin grafts.

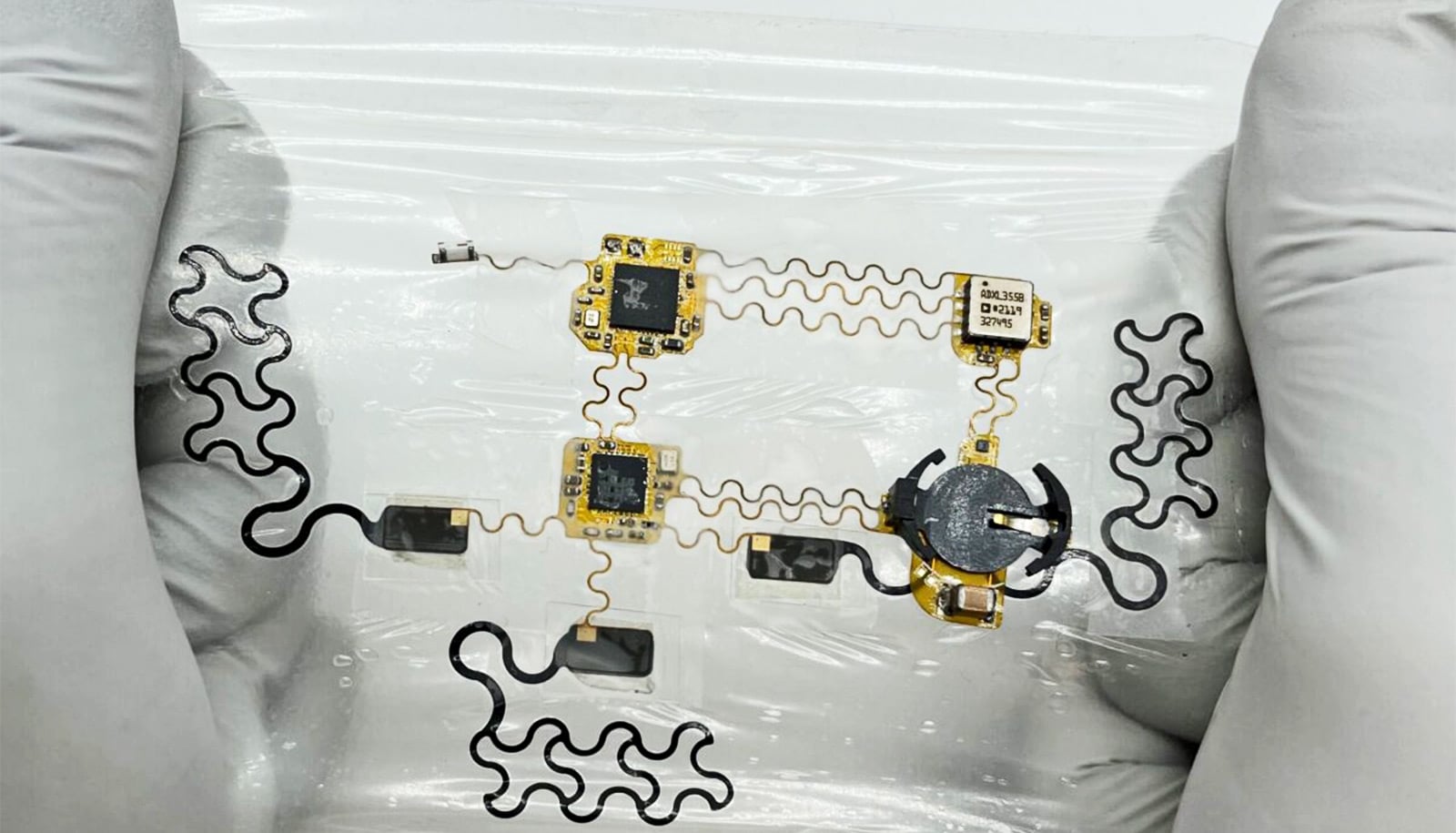

Underpinning all these studies is a controllable, stable, and reproducible method to make the right cells for transplantation using laminins—proteins that have a major role in the interactions of cells with their surrounding structures. Laminins exist in different forms depending on their environment and play a key role in directing the development of specific tissue cell types. In this study, stem cells were differentiated into heart muscle cells by growing them on the type of laminin abundantly found in the heart.

“To ensure patient safety, it is imperative that cell-based therapies show consistent efficacy and reproducible results. By extensive molecular and gene expression analyses, we demonstrated that our laminin-based protocol for generating functional cells to treat heart disease is highly reproducible,” says coauthor Enrico Petretto, associate professor and director of the Centre for Computational Biology at Duke-NUS.

The technology has been licensed to a Swedish biotech startup earlier this year to further promote the development of cell-based regenerative cardiology.

Source: Duke-NUS