Using the Las Cumbres Observatory (LCO), astrophysicists have been able to observe an exploding star slamming into a nearby companion star, detecting the fleeting blue glow caused by the interaction at an unprecedented level of detail.

The identity of this particular companion has been hotly debated for more than 50 years. Prevailing theory over the last few years has held that the supernovae happen when two white dwarfs spiral together and merge. The new study demonstrates that the supernova collided with a companion star that was not a white dwarf. White dwarf stars are the dead cores of what used to be normal stars like the sun.

“We’ve been looking for this effect—a supernova crashing into its companion star—since it was predicted in 2010,” says lead author Griffin Hosseinzadeh, a graduate student at the University of Califoria, Santa Barbara. “Hints have been seen before, but this time the evidence is overwhelming.”

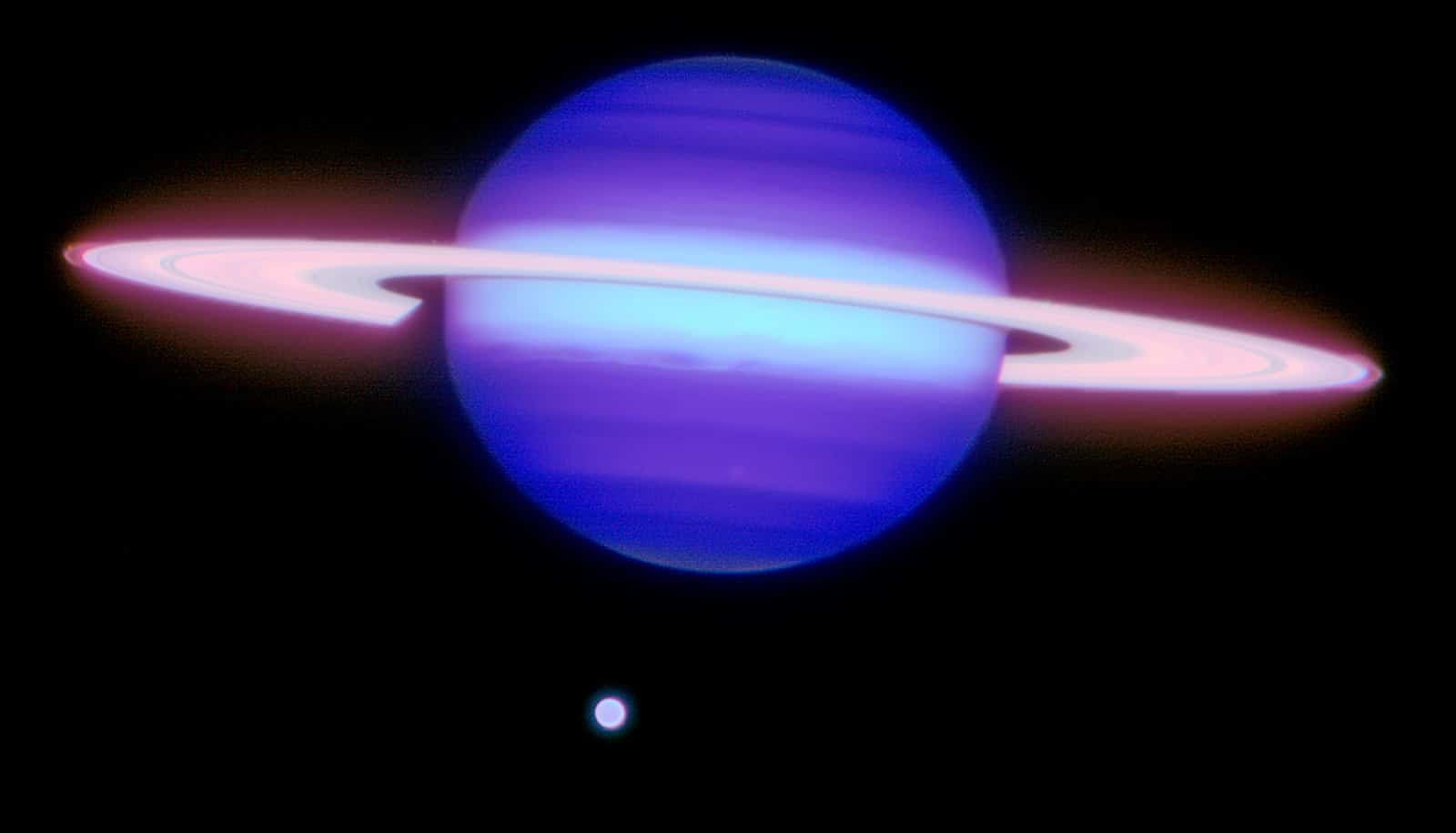

The supernova in question is SN 2017cbv, a thermonuclear Type Ia, which astronomers use to measure the acceleration of the expansion of the universe. This kind of supernova is known to be the explosion of a white dwarf star, though it requires additional mass from a companion star to explode.

“The universe is crazier than science fiction authors have dared to imagine.”

The new findings imply that the white dwarf was stealing matter from a much larger companion star—approximately 20 times the radius of the sun—which caused the white dwarf to explode. The collision of the supernova and the companion star shocked the supernova material, heating it to a blue glow heavy in ultraviolet light. Such a shock could not have been produced if the companion were another white dwarf star.

“The universe is crazier than science fiction authors have dared to imagine,” says Andy Howell, a staff scientist at LCO and Hosseinzadeh’s doctoral adviser. “Supernovae can wreck nearby stars, too, releasing unbelievable amounts of energy in the process.”

‘Heavy metal’ sheds light on super-charged supernovas

Coauthor David Sand, an associate professor at the University of Arizona, discovered the supernova on March 10, 2017, in the galaxy NGC 5643.

Only 55 million light years away, SN 2017cbv was one of the closest supernovae discovered in recent years, found by the DLT40 survey using the Panchromatic Robotic Optical Monitoring and Polarimetry Telescope (PROMPT) in Chile, which monitors galaxies nightly at distances less than 40 megaparsecs (120 million light-years).

This was one of the earliest catches ever—within a day, perhaps even hours, of its explosion. The DLT40 survey was created by Sand and study coauthor Stefano Valenti, an assistant professor at UC Davis; both were previously postdoctoral researchers at LCO.

Within minutes of discovery, Sand activated observations with LCO’s global network of 18 robotic telescopes, spaced around the Earth so that one is always on the night side. This allowed the team to take immediate and near-continuous observations.

“With LCO’s ability to monitor the supernova every few hours, we were able to see the full extent of the rise and fall of the blue glow for the first time,” Hosseinzadeh says. “Conventional telescopes would have had only a data point or two and missed it.”

Rare supernova shows up 4 times across the sky

The event is like gaining astronomical superpowers that give astronomers the ability to see the universe in new ways, Howell says. “These capabilities were just a dream a few years ago. But now we’re living the dream and unlocking the origins of supernovae in the process.”

The findings appear in the journal Astrophyiscal Journal Letters.

Source: UC Santa Barbara