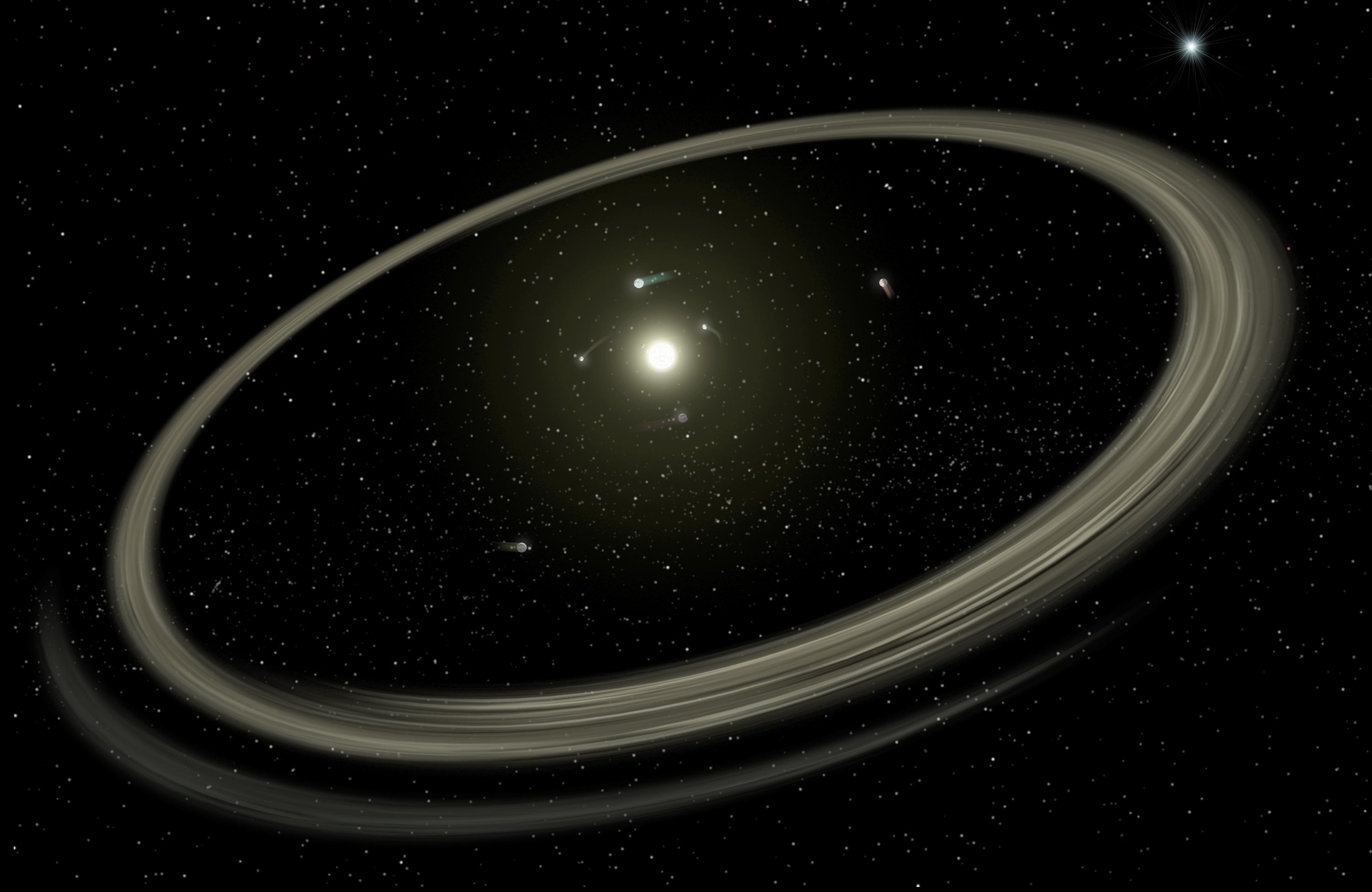

Researchers have developed a new method for better understanding the relationship between a star’s chemical composition and planet formation.

The researchers found that the majority of stars in their dataset are similar in composition to the sun, somewhat at odds with earlier work and implying that many stars in the Milky Way could host their own Earth-like planets.

The most common technique for finding exoplanets, ones that exist outside of the solar system, involves the transit method, when an exoplanet moves between its star and the observer and causes a dip in the star’s brightness. While most of the known exoplanets have been discovered using this method, this approach is limited because exoplanets can only be detected when their orbit and the observer are perfectly aligned and have short enough orbiting periods.

The second most powerful technique, the radial velocity or Doppler method, has other limitations in its ability to find planets.

This raises the question, If planets can’t be detected around a star, can their existence be inferred by studying the host star? The researchers found that the answer to this question is a qualified yes, with new methods helping astronomers better understand how the formation of exoplanets is related to the composition of the star they orbit.

“The idea is that planets and stars are born out of the same natal cloud, so you can imagine a scenario where a rocky planet locks on to enough material to leave the late stellar surface depleted in those elements,” says Jacob Nibauer, a recent graduate from the University of Pennsylvania who led the study for his senior thesis with Bhuvnesh Jain while under co-supervision by former postdoc Eric Baxter.

“The goal is to answer whether planet-hosting stars look different than stars with no planets, and one way to do that is to search for signatures of planet formation in the composition of the stellar surface,” Nibauer says. “Fortunately, the composition of a star, at least of its outer layers, can be inferred from its spectrum, the distribution of light intensity over different frequencies.”

To do this, the researchers used data from the Apache Point Observatory Galactic Evolution Experiment (APOGEE-2), focusing on 1,500 Milky Way galaxy stars with chemical composition data for five different elements. Nibauer’s novel contribution was to apply Bayesian statistics to measure the abundance of five rock-forming, or “refractory”, elements and objectively separate populations of stars based on their chemical compositions.

Nibauer’s method allows researchers to look at stars with low signal-to-noise ratios, or where measurement background can be larger than the star’s own signal.

“This framework, rather than focusing on a star-by-star basis, combines measurements across the entire population allowing us to characterize the global distribution of chemical abundances,” says Nibauer. “Because of that, we’re able to include much larger populations of stars compared with previous studies.”

The researchers found that their dataset neatly separated stars into two populations. Depleted stars, which make up the majority of the sample, are missing refractory elements compared to the not-depleted population. This could indicate that the missing refractory material in the depleted population is locked up in rocky planets.

These results are consistent with other smaller, targeted studies of stars that use more precise chemical-composition measurements. However, the interpretation of these results differs from previous studies in that the sun appears to belong to a population which makes up the majority of the sample.

“Previous studies were sun-centric, so stars are either like the sun or not, but Jake developed a methodology to group similar stars without referencing the sun,” says Jain. “This is the first time that a method which ‘let the data speak’ had found two populations, and we could then place the sun in one of those groups, which turned out to be the depleted group.”

This study also provides a promising avenue to identify individual stars which may have a higher likelihood of hosting their own planets, says Nibauer.

“The long-term goal is to identify large populations of exoplanets, and any technique that can place a probabilistic constraint on whether a star is likely to be a planet host without having to rely on the usual transit method is very valuable,” he says.

And if Milky Way stars being depleted is the norm, this could mean that the majority of these stars could be orbited by Earthlike planets, opening up the possibility that stars that are “missing” heavier elements simply have them locked up in orbiting rocky exoplanets, though other possible connections to exoplanets are also being explored.

“This would be exciting if confirmed by future analyses of larger datasets,” says Jain.

The researchers presented the results at the 238th American Astronomical Society conference and they will appear in The Astrophysical Journal.

Additional coauthors are from Penn, the University of Hawaii, Princeton University, and the Earth and Planets Laboratory Carnegie Institution of Washington.

Support for this research came from NASA and the University of Pennsylvania through the Center for Undergraduate Research and Fellowships.

Source: University of Pennsylvania