A wildflower’s spiny pollen has evolved to attach to traveling bumblebees, research finds.

Over 80% of the world’s flowering plants must reproduce in order to produce new flowers, according to the US Forest Service. This process involves the transfer of pollen between plants by wind, water, or insects called pollinators—including bumblebees.

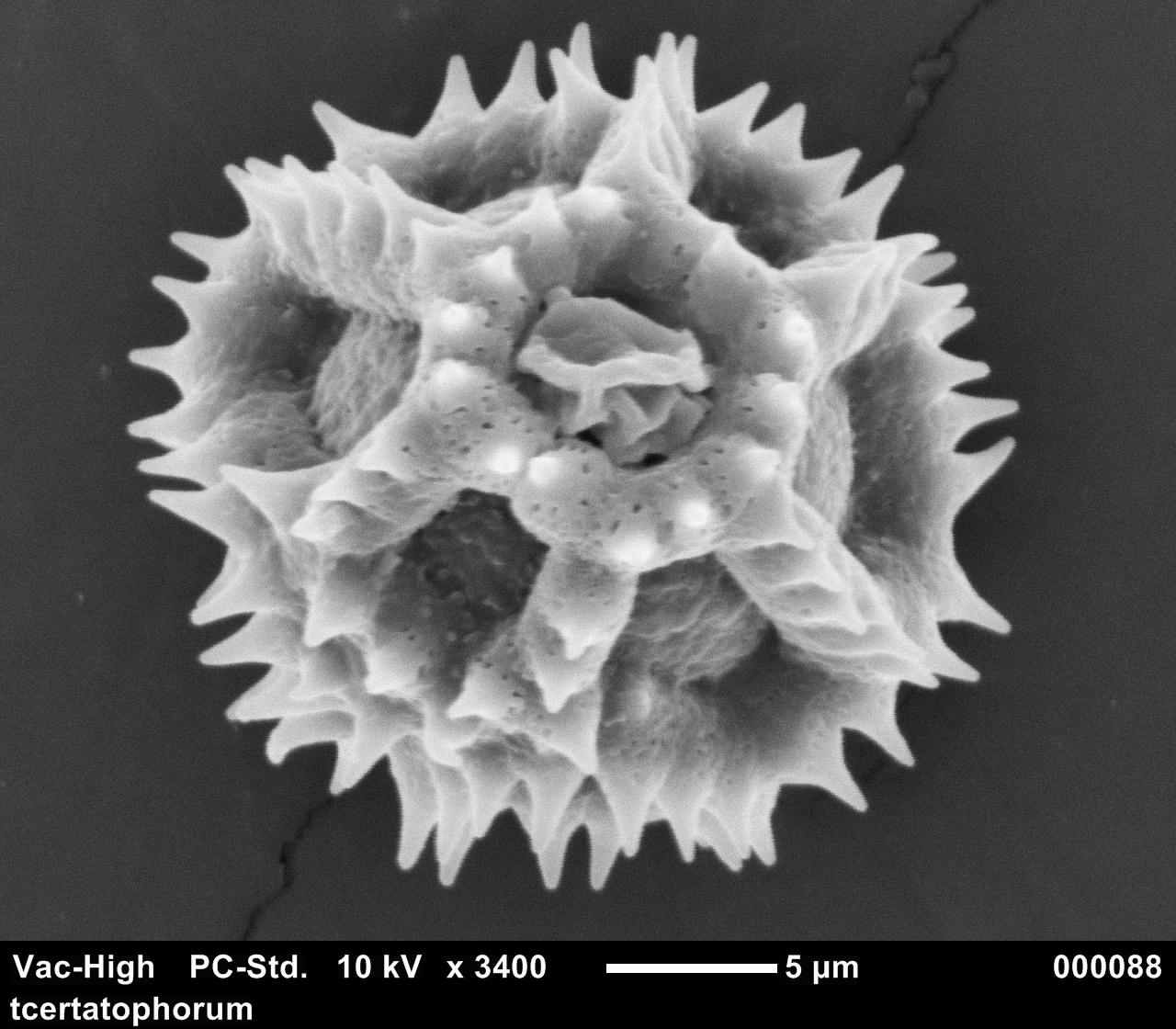

In a new study, researchers at the University of Missouri focused on the spiny pollen of a native wild dandelion species in the southern Rocky Mountains. Using a highly detailed electron scanning microscope, the research team could observe the microscopic surface of the spiny pollen, which otherwise looks like yellow dust to the naked eye.

“We observed this native pollen from the Rockies has optimally spaced spines that allow it to easily attach to a pollinator, such as a bumblebee,” says Austin Lynn, a recent PhD graduate in biology of the University of Missouri Division of Biological Sciences.

“When we compared that with the average lawn dandelion, which does not need pollen to reproduce, we saw that the pollen on the lawn dandelion has a shorter distance between these spines, making it harder to attach to traveling pollinators. Therefore, we show this wild dandelion pollen has evolved over many generations to create an optimal shape for attaching to pollinators.”

Previous studies have examined spiny pollen, but this is one of the first studies focusing on the pollen’s spines. Lynn, the lead researcher of the study, says the researchers were also able to refute a competing idea that spiny pollen serves as a defensive mechanism to protect the pollen from being eaten.

“The spiny pollen actually acts like Velcro,” Lynn says. “So, when bees are harvesting pollen for food, this pollen is sticking to their hair. It’s a great example of mutualism where the plant needs the pollinator to reproduce and the pollinator needs the plant for its food.”

The researchers plan to study how a bumblebee’s hairs contribute to this process.

The study appears in the American Journal of Botany. Coauthors are from the University of Missouri and Colorado State University. Funding came from the Mountain Area Land Trust and a Cherng Foundation Scholarship. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Source: University of Missouri