Soft corals in the US Virgin Islands have recovered from nearly back-to-back Category 5 hurricanes in 2017, but stony corals continue to decline, researchers report.

The story of these apparently hardy communities of colorful marine life is part of a larger, rapidly shifting narrative surrounding the future of coral reefs, according to the new study.

The recently realized resilience of the soft corals is an important development toward our increasing understanding of these complex ecosystems, but the findings in Scientific Reports puts that seemingly good news in the context of an ecosystem that is dramatically changing.

“These soft corals are resilient,” says Howard Lasker, a professor in the environment and sustainability department and the geology department at the University at Buffalo and an expert on the ecology of coral reef organisms.

“But right now, in the Caribbean we’re seeing a drastic decline of stony corals, and the soft corals are not a simple replacement for what’s being lost.”

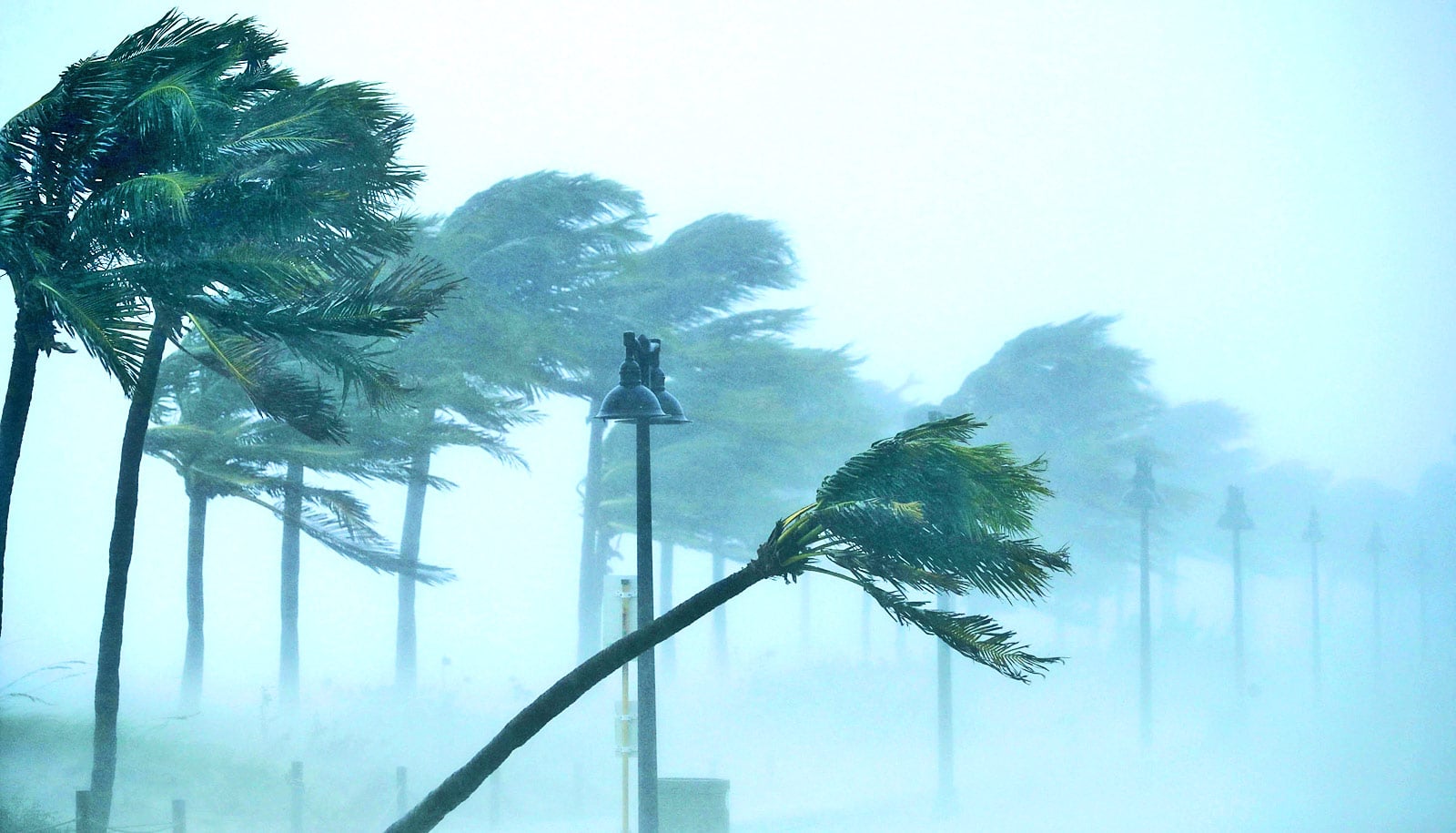

Soft corals, also known as octocorals, are branching colonial organisms. The colonies with their impressionistic tree-like appearance sway in ocean currents like trees in a storm.

Stony corals, which also form colonies, produce rigid skeletons and create the framework of coral reefs. The living animal sits atop the structure they create, slowly secreting calcium carbonate, essentially limestone, to build up the reef.

These corals inspire tourist destinations that on a more practical level play diverse ecological, economic, and environmental roles, serving a variety of functions, such as protecting shorelines from erosion and providing habitats for a diverse population of marine life.

While the soft corals are doing fine, stony corals have declined as much as 40% in recent decades, says Lasker, whose team examined three reefs on the south shore of St. John (part of the US Virgin Islands) following Hurricanes Irma and Maria, storms that passed within two weeks of one another in September 2017.

The researchers compared data from the storm’s aftermath with sampling that began in 2014 and continued in 2018.

“The octocoral communities we studied suffered dramatic declines with the passage of these hurricanes. In that sense, they weren’t resistant to the effects of severe storms,” says Lasker. “However, they showed resilience—the ability to recover.

“We found that many colonies were killed, but two years later it hadn’t changed the nature of species distribution, and as importantly new colonies were developing making up for the losses.”

This pattern of loss and recovery was emblematic historically of stony corals as well, but that’s no longer the case for the scleractinians. Lasker says while their soft coral counterparts provide shelter for many reef animals, they won’t build the hard physical structure of reefs.

“One of the big questions in marine ecology is what we should be doing,” says Lasker. “Should we be trying to remediate the damage and attempt to prevent species loss by creating protected environments?”

There is a range of opinions about taking the curator’s approach to the reefs, but what is certain is that these systems are already dramatically different from descriptions made during the 1950s. And those observations from the ’50s stand in obvious contrast to what European explorers would have seen when they encountered the reefs centuries ago.

“Humans are responsible for the changes,” says Lasker. “It’s really pretty simple: land use, sediments, sewage, agricultural runoff, overfishing, and now climate change.”

As the stony corals wane the soft corals replace them, but the reason the stony corals aren’t recovering comes back to us, Lasker says.

“It’s important to recognize that the resilience we’re seeing in these communities may decline with the frequency and intensity of future storms,” says Lasker. “This could be a temporary state. The real test will come when we examine these areas 10 years down the road.”

Source: University at Buffalo