The use of medication to treat sleep disturbances has fallen dramatically in the United States in recent years after several decades of climbing steeply, according to new research.

The study in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine documented a 31% decline in the use of common sleep medications between 2013 and 2018, a trend thought to be linked to a greater awareness of the potential pitfalls posed by these prescriptions. (It remains to be seen how the COVID-19 pandemic might have impacted this trend.)

The drop-off is particularly noteworthy for Americans over age 80, who are most susceptible to falls leading to injury when using sleep medications. The study showed an 86% decrease in this group.

“I was surprised and encouraged by the results because there’s been a great deal of effort to minimize the long-term use of these pharmaceutical agents,” says public health researcher Christopher Kaufmann, an assistant professor in the University of Florida College of Medicine’s department of health outcomes and biomedical informatics and a member of the university’s Institute on Aging.

“We’ve seen de-prescribing initiatives,” he adds. “A number of medical organizations, advocacy groups, and policymakers have also strongly discouraged the use of these drugs to treat insomnia due to potential adverse outcomes associated with their use. There are highly effective behavioral treatments available that are growing in popularity.”

“…there also is a risk with having untreated insomnia.”

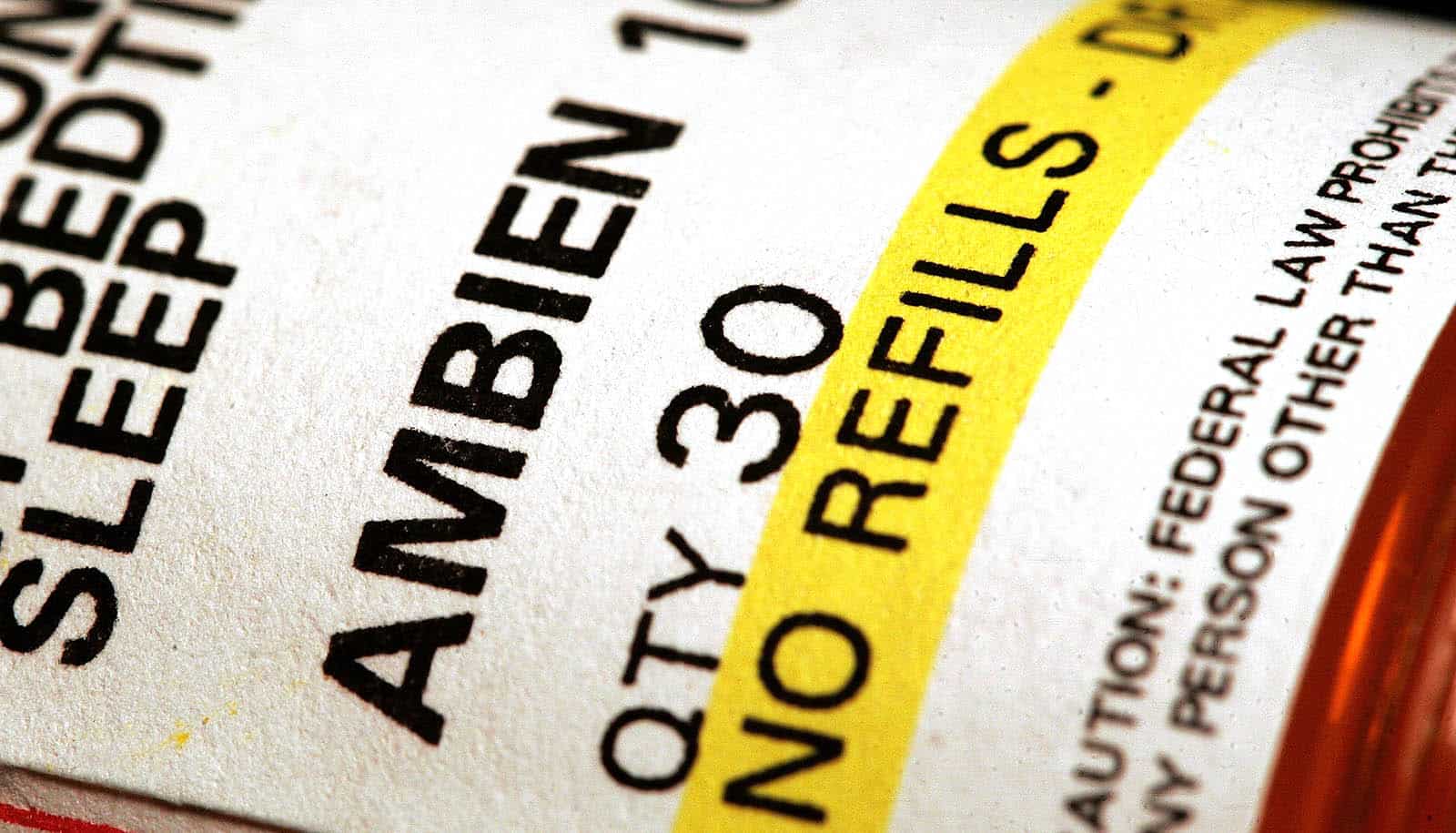

The study’s observed trend stands in marked contrast to the rapid rise of sleep medication use and prescribing in previous decades. An earlier study by some of the same researchers found that prescriptions for benzodiazepines, or BZDs, a class of drugs to treat anxiety and insomnia that includes diazepam (Valium) and alprazolam (Xanax), and non-BZDs, a similar class of medications including zolpidem (Ambien), climbed 69% and 140%, respectively, between 1993 and 2010.

Kaufmann believes there are multiple reasons for the rise, including direct-to-consumer marketing, particularly with the emergence of Ambien in the early 1990s. He also says a greater awareness of the importance of sleep to general health played a critical role.

The researchers analyzed data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, conducted every two years. Participants were asked to bring drugs they had used in the previous month or a pharmacy printout to their visits with researchers, who also inquired about the reason medication was being used. Researchers focused on medications specifically used for insomnia and other transient sleep difficulties.

While the use of sleep medications dropped across all drug classes, the study found the strongest decrease in FDA-approved medications, which fell 55%. (Other sleep drugs are prescribed on an off-label basis.)

The study noted BZDs and other hypnotics have been associated with the risk of motor vehicle accidents, memory impairment, and, in older groups, falls and hip fractures. Indeed, in 2019 the US Food and Drug Administration required the placement of a “black box warning” on prescriptions of non-BZD hypnotics such as eszopiclone (Lunesta), zolpidem (Ambien), and zaleplon (Sonata).

“Past research has shown that risk of these poor outcomes increases the longer patients use these medications,” says Kaufmann.

Physicians increasingly encourage behavioral treatments for insomnia. The gold standard, Kaufmann says, is cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, a program involving multiple visits to a sleep specialist to change behaviors or poor habits that cause sleep loss.

But access to such care can be limited because of a dearth of providers, Kaufmann says. “Digital therapeutics” have grown in popularity, he notes. This is software accessed on a smartphone or computer that offers behavioral techniques to treat insomnia without a visit to a sleep specialist. These apps can include a virtual coach teaching lessons on building better sleeping habits and allow users to track their improvement over the course of a multiweek program.

Kaufmann says these behavioral treatments have been shown to be at least as effective or even more effective than sleep drugs.

Atul Malhotra, the study’s senior author and a pulmonologist, intensivist, and research chief of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine at the University of California, San Diego, says a move away from sleep drugs is a good thing.

But he says he didn’t want to portray these drugs as inappropriate for everyone. If behavioral treatments fail, medication might be the best option to lessen the health risks associated with chronic insomnia, which include heart disease, high blood pressure, and depression.

“I think these medications can be quite useful for some patients,” Malhotra says. “There is a stigma attached to being on Valium or Ambien long-term. People think it’s a problem. And I’d certainly rather not be on those medications than on them. But we need to remember there also is a risk with having untreated insomnia. There are ill effects of poor sleep that can’t be ignored.”

Coauthors of the study are from Johns Hopkins University; the University of Maryland; and the University of California, Los Angeles.

Source: Eric Hamilton for University of Florida