Scientists have developed and refined a blood test that could help clinicians identify infants who may have had bleeding of the brain as a result of abusive head trauma, sometimes referred to as shaken baby syndrome.

The serum-based test, which needs to be validated in a larger population and receive regulatory approval before being used in clinical practice, would be the first of its kind to be used to detect acute intracranial hemorrhage, or bleeding of the brain. Infants who test positive would then have further evaluation via brain imaging to determine the source of the bleeding.

“Abusive head trauma (AHT) is the leading cause of death from traumatic brain injury in infants and the leading cause of death from physical abuse in the United States,” says senior author Rachel Berger, and professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and chief of the Child Advocacy Center at Children’s Hospital.

However, approximately 30 percent of AHT diagnoses are missed when caretakers provide inaccurate histories or when infants have nonspecific symptoms such as vomiting or fussiness. Missed diagnoses can be catastrophic as AHT can lead to permanent brain damage and even death.

Berger and colleagues have long been researching approaches to detect acute intracranial hemorrhage in infants at risk.

‘Fracture prints’ may help solve child abuse cases

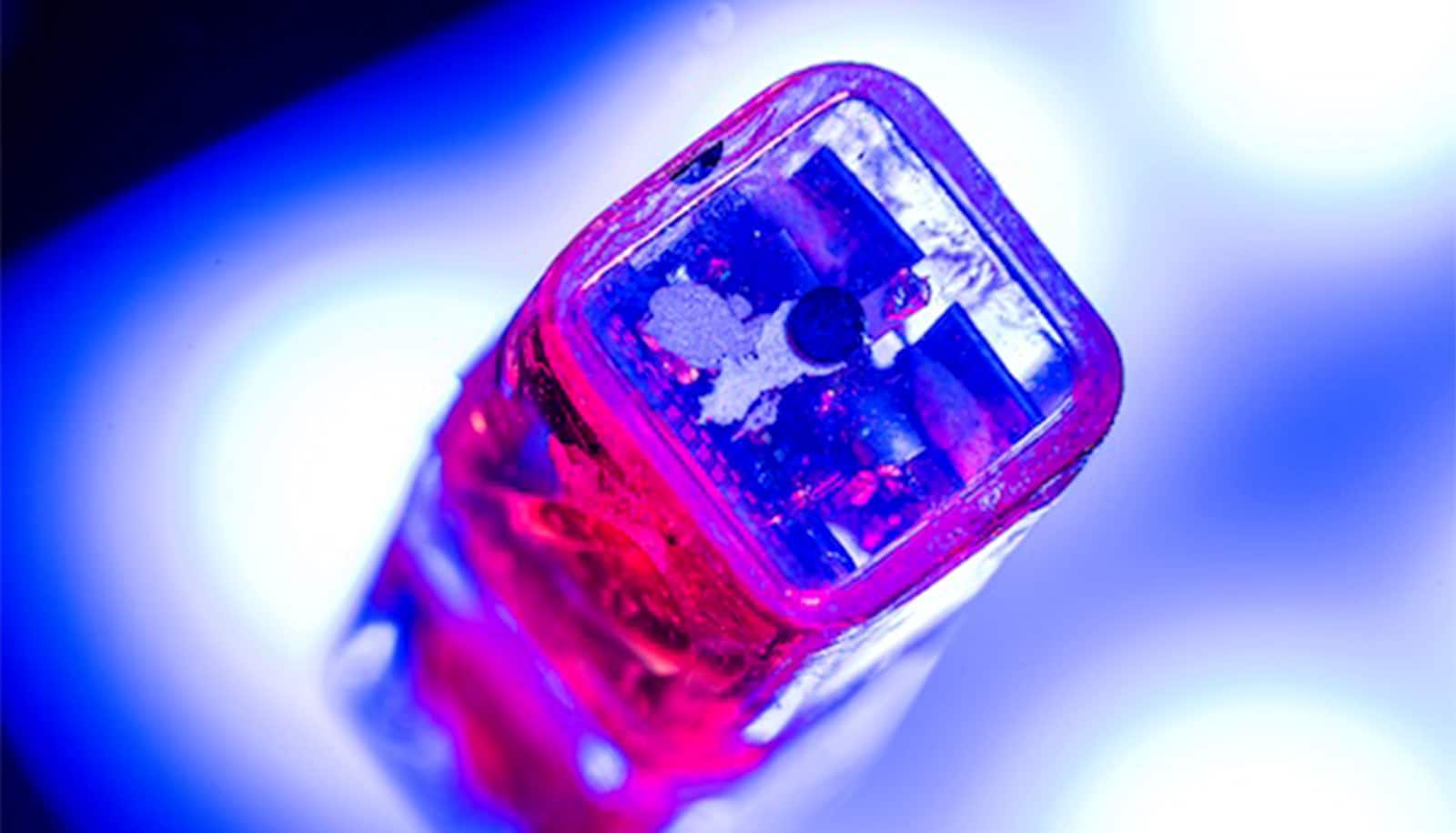

In the current study, published in JAMA Pediatrics, researchers collaborated with Axela, a Canadian molecular diagnostics company, to develop a sensitive test that could reduce the chances of a missed diagnosis by using a combination of three biomarkers along with a measure of the patient’s level of hemoglobin, the protein that carries oxygen in blood.

Axela’s automated testing system allowed the researchers to measure multiple biomarkers simultaneously using an extremely small amount of blood, an important characteristic of a test for infants.

To arrive at the formula, called the Biomarkers for Infant Brain Injury Score (BIBIS), for discriminating between infants with and without intracranial hemorrhage, researchers used previously stored serum samples from a databank established at the Safar Center.

The team then evaluated the predictive capacity of the BIBIS value in a second population of 599 infants who were prospectively enrolled at three study sites in the United States. In addition to Children’s Hospital, infants were enrolled at Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago and Primary Children’s Hospital in Salt Lake City.

After child abuse, impulses are harder to control

The test correctly detected acute intracranial hemorrhage because of abusive head trauma approximately 90 percent of the time, a much higher rate than the sensitivity of clinical judgement, which is approximately 70 percent.

“The test is not intended to replace clinical judgement, which is crucial,” Berger says. “Rather, we believe that it can supplement clinical evaluation and in cases where symptoms may be unclear, help physicians make a decision about whether an infant needs brain imaging.”

The specificity of the test—or the ability to correctly identify an infant without bleeding of the brain who would not require further evaluation—was 48 percent. Researchers aimed for the test to be highly sensitive rather than maximizing accuracy, since missing a diagnosis has more serious consequences than performing brain imaging in babies without the condition.

“This study illustrates the benefits of being able to perform highly sensitive tests at the point of care,” says Paul Smith, president and CEO of Axela and coauthor of the study.

Additional researchers from the University of Pittsburgh, Axela Inc., the University of Utah, and Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital are coauthors of the study. The University of Pittsburgh, Berger, and Axela have filed a joint US patent for the test.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work.

Source: University of Pittsburgh