Known for its role in relieving depression, the neurochemical serotonin may also help the brain execute instantaneous, appropriate behaviors in emergency situations, according to a new study.

The researchers studied brain activity patterns in mice. If a mouse was experiencing a threat, dorsal raphe serotonin neurons would fire during movements. But, when there was a calm, positive environment, these serotonin neurons would fire during pauses in active behavior.

“This switch really surprised us,” says senior author Melissa Warden, assistant professor and a fellow in the neurobiology and behavior department at Cornell University. “It was our first clue that something really strange might be going on in the brain in emergency situations.”

In emergency fight-or-flight situations, behavioral choices are different from the decisions an animal might make in less-critical situations. For example, if a mouse sits in the middle of an exposed field and a hawk spies it for food, the mouse may see the hawk start to swoop in and the mouse’s survival instinct tells it to run. The escape response is appropriate, Warden says.

“But if the hawk is flying overhead and it hasn’t seen the mouse, but the mouse has seen the hawk, it is appropriate for the mouse to freeze in place to avoid being detected,” she says.

“In this situation, freezing in place is a better decision than attempting to flee, because the odds of survival are higher.”

In high-threat situations, stimulating serotonin neurons elicits escape attempts. In lower threat environments, stimulating these neurons causes pausing.

Thus, stimulating serotonin neurons is probably promoting the context-appropriate response. “It may cause animals to react to their environment, to do what’s appropriate in light of the current situation,” Warden says.

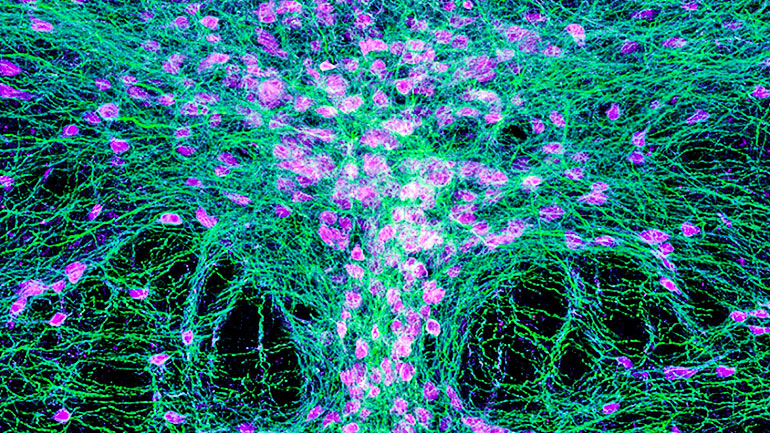

Like a global command center, serotonin sends signals all over the brain, she says. Fully understanding how this system prompts different behaviors in different environments may shed light on the role of other systems in the brain.

“Considering the widespread distribution of serotonin neurons throughout the brain, this finding raises the possibility that the ’emergency brain’ operates in a fundamentally different way,” Warden says.

The study appears in Science. The National Institutes of Health, the New York Stem Cell Foundation, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the Whitehall Foundation, the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, the Mong Family Foundation, and Cornell funded the study.

Source: Cornell University