Imagine a liquid that could move on its own without human effort or the pull of gravity. You could put it in a container flat on a table, not touch it in any way, and it would still flow.

As reported in Science, researchers have taken the first step in creating a self-propelling liquid. The finding offers the promise of developing an entirely new class of fluids that can flow without human or mechanical effort.

One possible real-world application: Oil might be able to move through a pipeline without pumps.

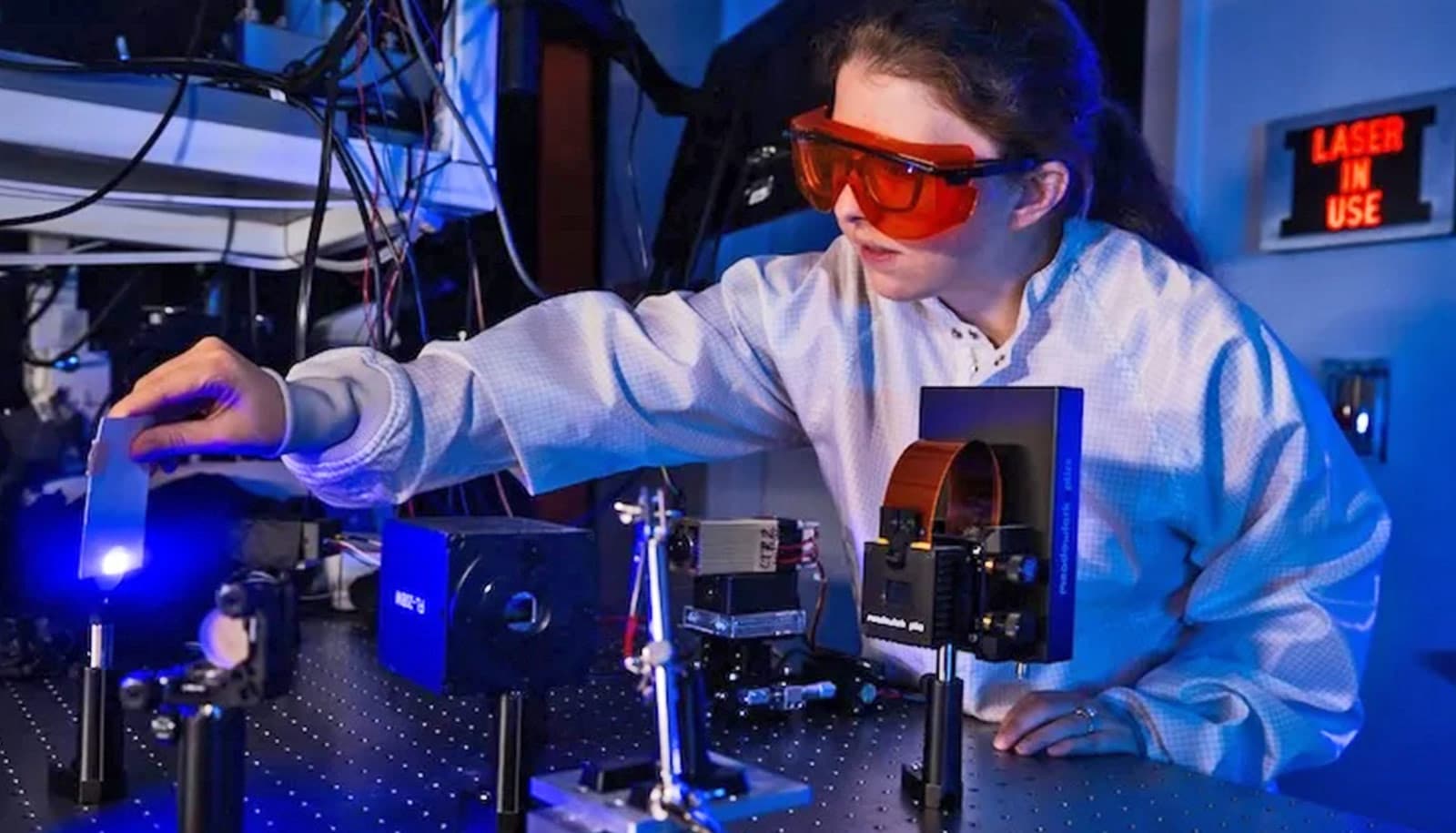

The researchers work at Brandeis University’s Materials Research Science and Engineering Center (MRSEC), part of a National Science Foundation initiative to create a revolutionary new class of materials and machines made from biological components.

The researchers reproduced in the lab the incredibly complex series of processes that allow cells to change shape and adapt to their environment. Cells can do this because the building blocks of its scaffolding—hollow cylindrical tubes called microtubules—are capable of self-transformation. The microtubules grow, shrink, bend, and stretch, altering the cell’s underlying structure.

The researchers extracted microtubules from a cow’s brain and placed them in a watery solution. They then added two other types of molecules found in cells—kinesin and adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

The microtubules aligned parallel to each other. A kinesin molecule came between them, connecting them like a tie between rail tracks.

Using the ATP as a fuel source, the kinesin began moving. Its top went in one direction, the bottom in another. The microtubules slid away from each other, and the structure broke apart.

But the microtubules didn’t remain free-floating for long. New kinesin came along and bound each to a new partner.

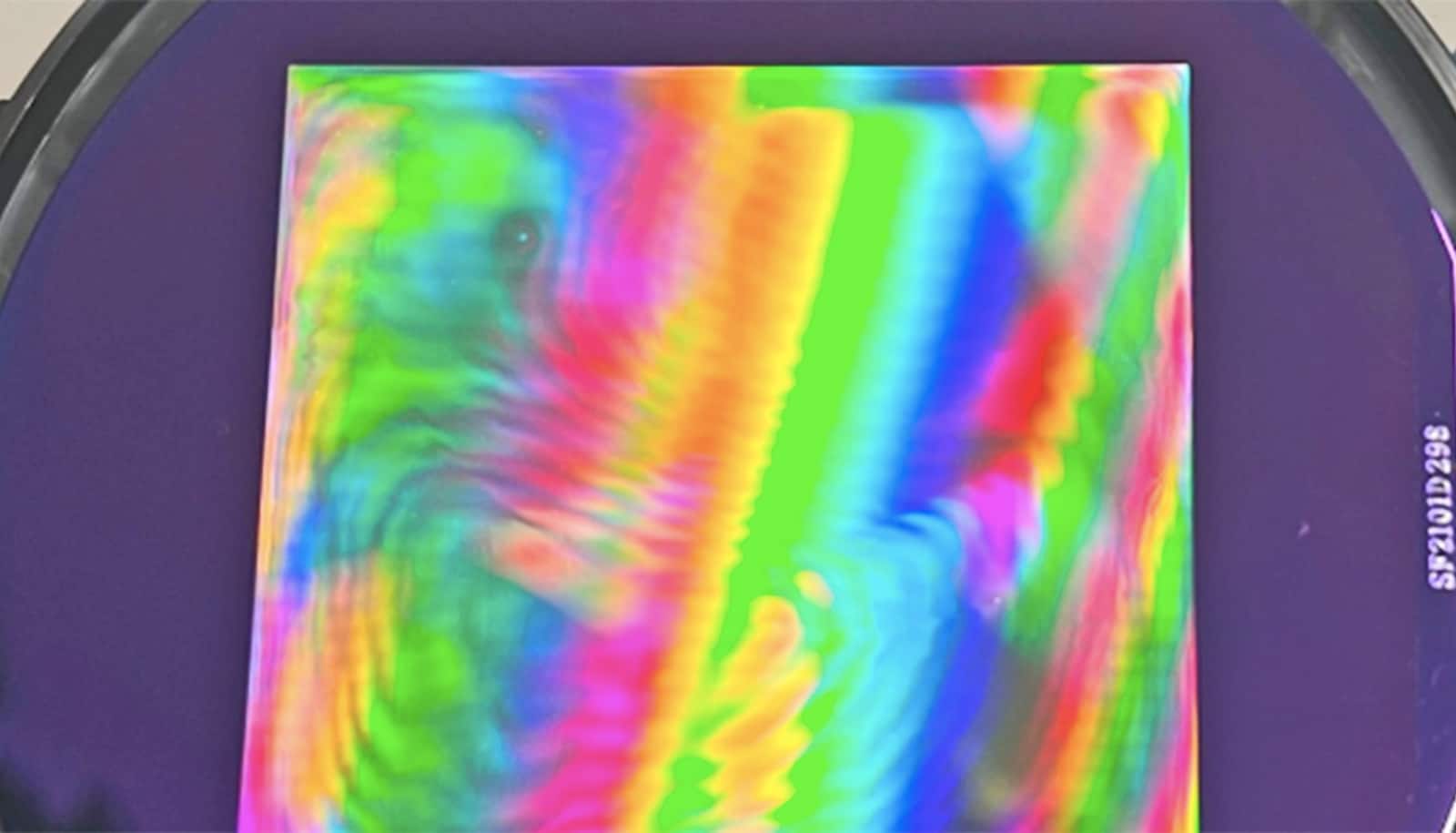

As these microtubules came together then separated, amazing, swirling patterns emerged in the fluid. And for the first time ever, the team was able to get the swirls to move in the same direction, creating a “coherent flow” that pushed the surrounding liquid forward as well.

Why baby starfish make pretty whorls in water

This microtubule-kinesin-ATP reaction is the same one that occurs in cells, except in cells it is much more complicated. Yet the new, much simpler model achieved a similar effect. Essentially the researchers harnessed the power of nature to create a microscopic machine capable of pumping fluid.

The first author of the paper is Kun-Ta Wu, a lecturer in physics. Additional coauthors are from Brandeis and Georgia Tech.

Source: Brandeis University