A completely new sauropodomorph dinosaur has been identified in Zimbabwe. The discovery is only the fourth dinosaur species discovered in that country.

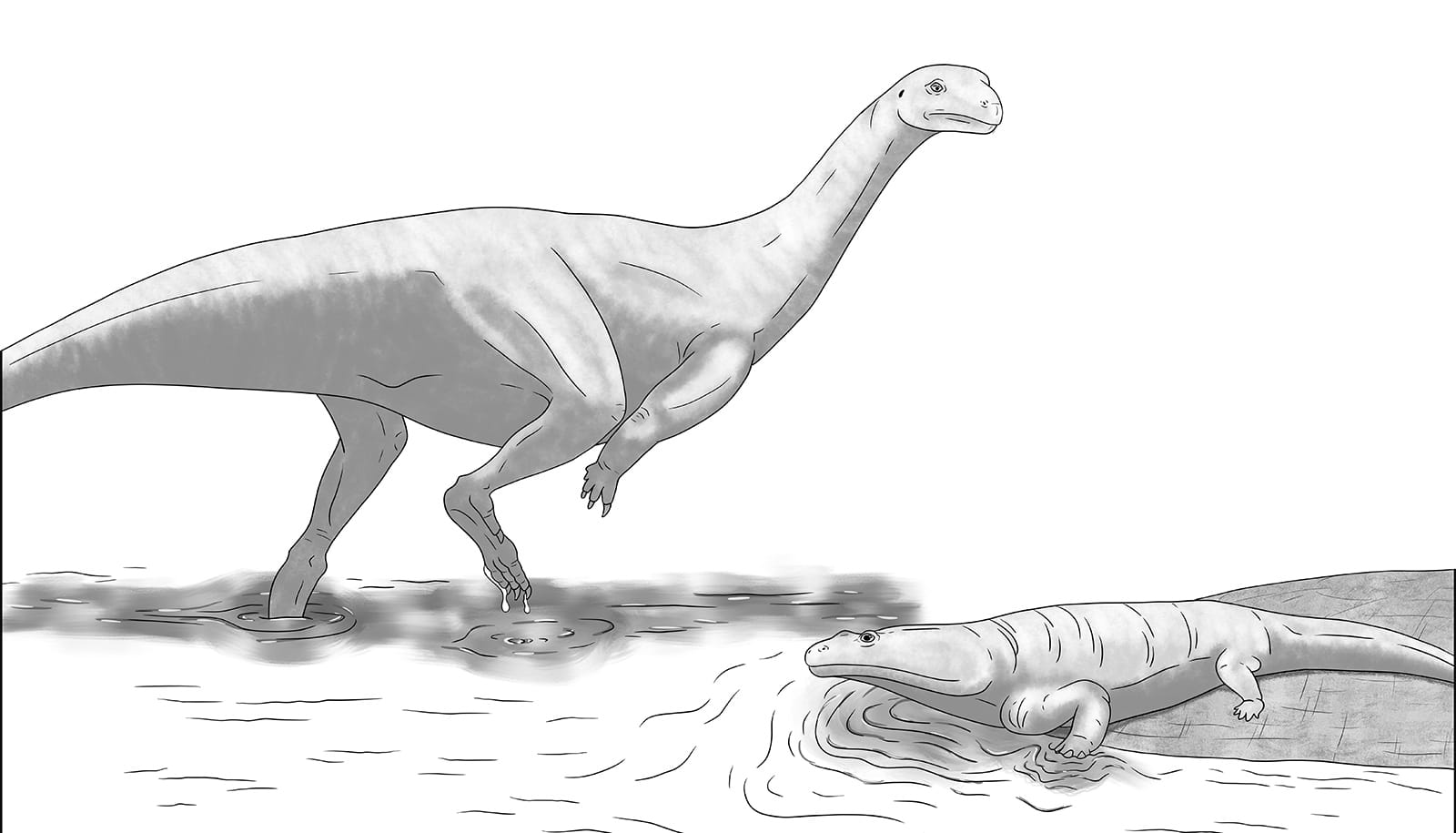

Long-necked herbivorous dinosaurs are known as sauropodomorphs. They were a group of mainly bipedal dinosaurs that lived some 210 million years ago in the Late Triassic.

Kimberley (Kimi) Chapelle, assistant professor in the anatomical sciences department in the Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University, is part of the international team of scientists that discovered and identified the find, named Musankwa sanyatiensis.

The discovery of Musankwa sanyatiensis is particularly significant as it is the first dinosaur to be named from the Mid-Zambezi Basin of northern Zimbabwe in more than 50 years. The fossil follows only these previous dinosaur discoveries in the region: Syntarsus rhodesiensis in 1969, Vulcanodon karibaensis in 1972, and Mbiresaurus raathi in 2022.

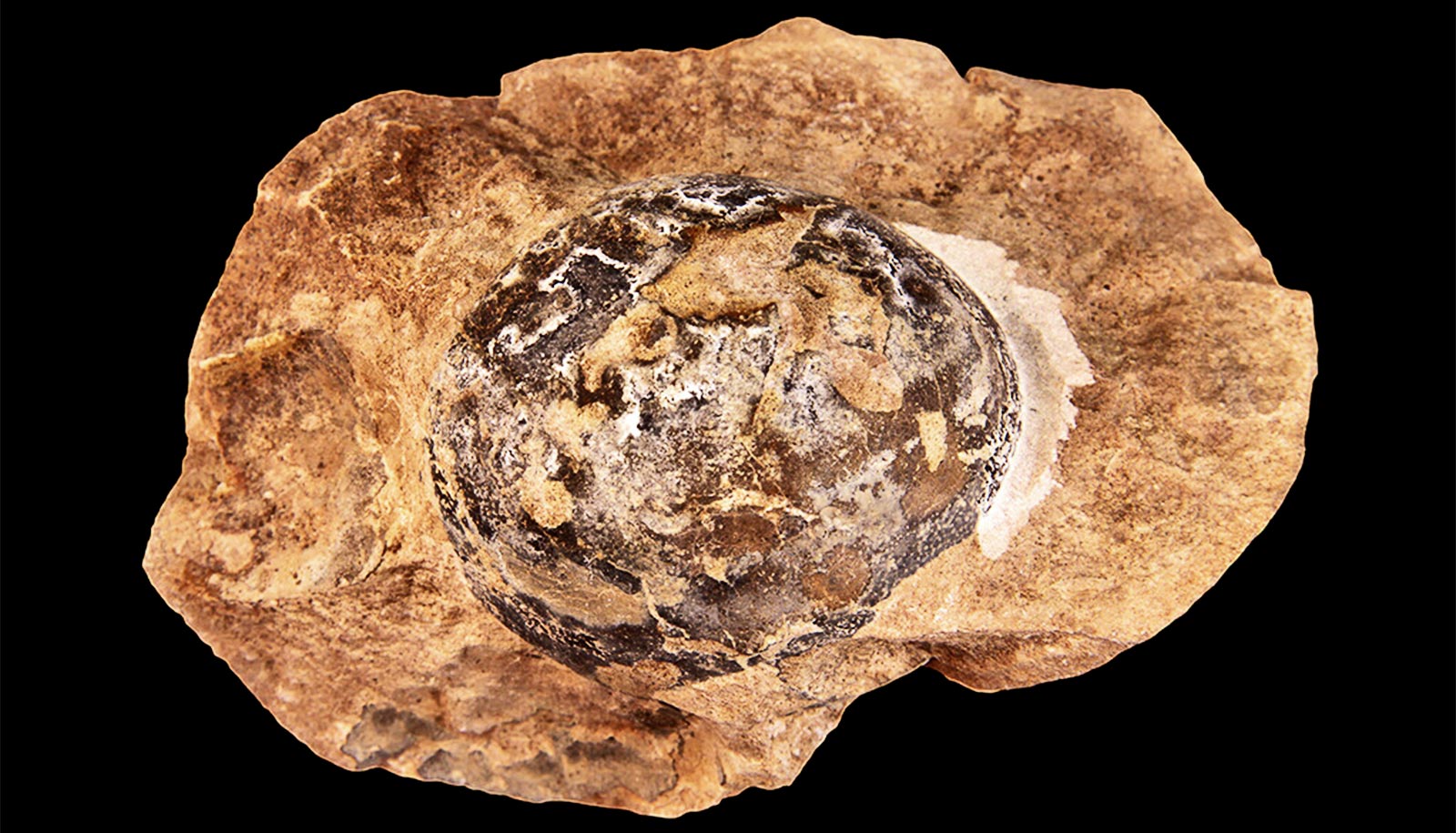

Musankwa sanyatiensis is represented by the remains of a single hind leg, including its thigh, shin, and ankle bones.

An evolutionary analysis reveals that Musankwa sanyatiensis was a member of the Sauropodomorpha, which were widespread during the Late Triassic. The dinosaur appears to be closely related to contemporaries in South Africa and Argentina. Weighing in at around 390 kilograms or about 850 pounds, the plant-eating Musankwa sanyatiensis, one of the larger dinosaurs of its era, dwelled mostly in swamp areas, the researchers say.

“Despite the limited fossil material, these bones possess unique features that distinguish them from those of other dinosaurs living at the same time,” says Chapelle, who helped excavate the specimen and was present at the field site on the day when Musankwa sanyatiensis was discovered in 2018.

Once the fossil had been micro-CT scanned, Chapelle processed the data and did the digital reconstructions of Musankwa sanyatiensis. She also assisted in describing the dinosaur and determining its position on the dinosaur family tree through phylogenetic analysis.

The fossil was named Musankwa sanyatiensis after the houseboat “Musankwa.” In the Tonga dialect, “Musankwa” means “boy close to marriage.” This vessel served as the research team’s home and mobile laboratory during two field expeditions to Lake Kariba in 2017 and 2018.

While Africa itself has a long history of dinosaur discoveries, there have been few in Zimbabwe and in that region of the continent. Lead author Paul Barrett, a professor from the Natural History Museum of London, explains that the likely reason for this is “undersampling,” as fewer paleontologists have searched though the region compared to other regions in countries around the world.

“Over the last six years, many new fossil sites have been recorded in Zimbabwe, yielding a diverse array of prehistoric animals, including the first sub-Saharan mainland African phytosaurs (ancient crocodile-like reptiles), metoposaurid amphibians (giant armored amphibians), lungfish, and other reptile remains,” Barrett says.

“Based on where it sits on the dinosaur family tree, Musanwka sanyantiensis is the first dinosaur of its kind from Zimbabwe,” adds Chapelle. “It, therefore, highlights the potential of the region for further paleontological discoveries.”

The authors believe that as more fossil sites are explored and excavated, there is hope for uncovering further significant finds in Zimbabwe and other regions that will shed light on the early evolution of dinosaurs and the ecosystems they inhabited.

The study appears in the journal Acta Palaeontologica Polonica.

Source: Stony Brook University