New research gauges how people in structural disadvantaged communities feel about police responding to mental health crises.

Police officers often respond to incidents that do not involve crime or immediate threats to public safety but instead deal with community members facing unmet mental health needs. In response to this, many cities are experimenting with co-deploying police officers alongside health professionals or deploying teams entirely composed of civilian health professionals.

Recently, researchers from the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing (Penn Nursing) explored the perspectives and preferences about these programs among residents in structurally disadvantaged areas where mental health distress is more common, mental health services are less accessible, and involvement with police is more frequent and fraught. The findings, published in the Journal of Community Safety & Well-Being, provide insights to guide efforts toward a healthier response to mental health crises.

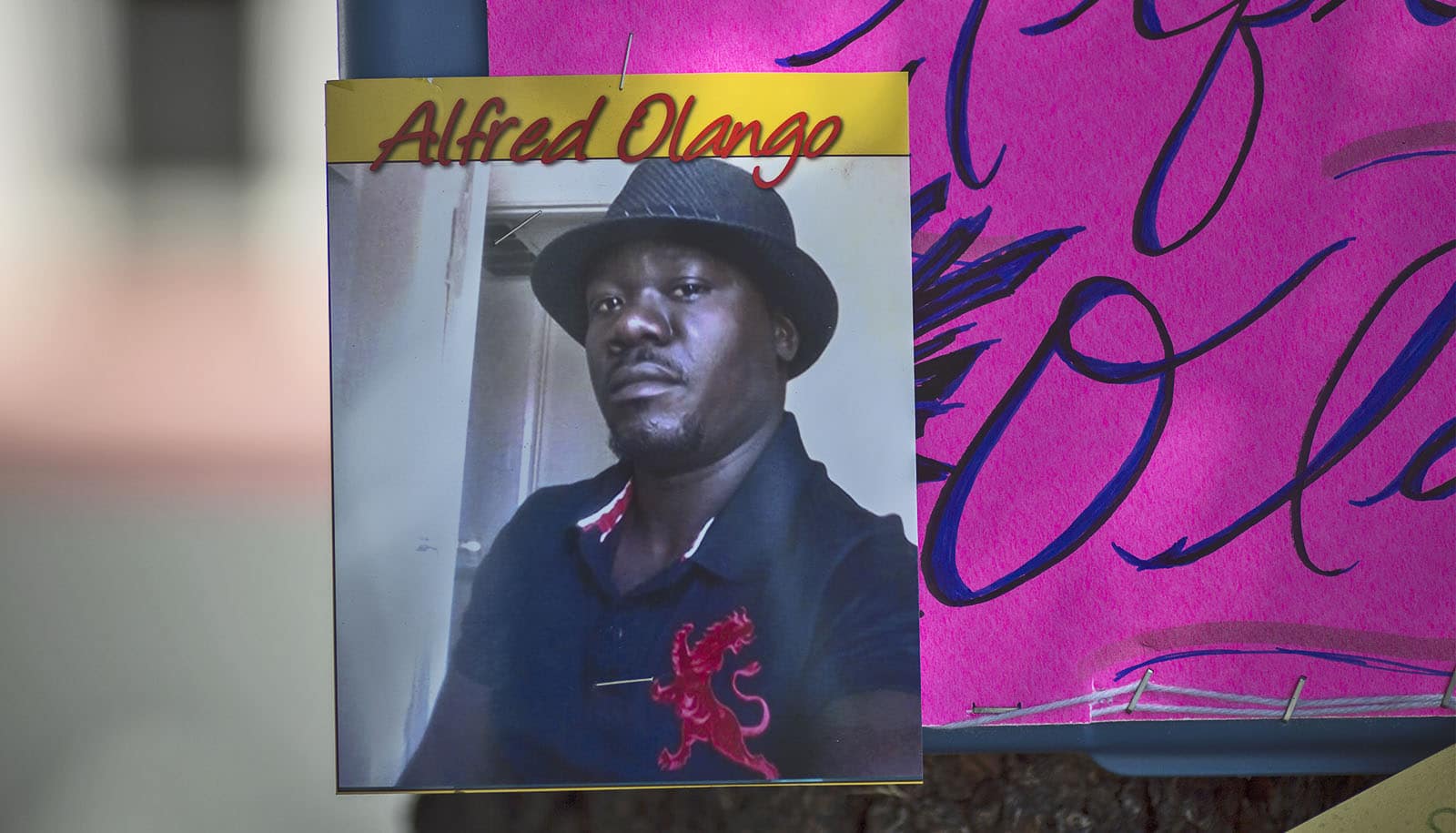

The study reveals that while many respondents suggested that police presence is necessary during the response to mental health crises because of the risk of violence, they were simultaneously uncomfortable with police officer involvement. The discomfort with police involvement was especially pronounced among younger and Black residents. However, support for co-deployment was high across all subgroups.

First author Helena A. Addison, a PhD fellow, emphasizes the importance of considering help-seeking norms and the concerns and experiences of historically underserved community members, who often possess significant apprehension regarding police involvement in crisis response. “We can all agree that we want police involved as little as possible as mental health first responders,” Addison notes, “and the perspectives of community members is essential to effectively identifying and scaling better systems for supporting people in moments of crisis.

Coauthors are from the Thomas Jefferson College of Population Health; Columbia University; and Temple University. This work had partial support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health.

Source: Penn