Scientists have used numerical simulations to investigate the origins of a large heart-shaped structure on the surface of the dwarf planet Pluto.

The “heart” has puzzled scientists ever since the cameras of NASA’s New Horizons mission discovered it in 2015 because of its unique shape, geological composition, and elevation.

The scientists focused on Sputnik Planitia, the western teardrop-shaped part of Pluto’s heart surface feature.

According to their research, Pluto’s early history was marked by a cataclysmic event that formed Sputnik Planitia: a collision with a planetary body a little over 400 miles in diameter, roughly the size of Arizona from north to south.

The team’s findings, published in Nature Astronomy, also suggest that the inner structure of Pluto is different from what was previously assumed, indicating that there is no subsurface ocean.

“The formation of Sputnik Planitia provides a critical window into the earliest periods of Pluto’s history,” says Adeene Denton, a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory and a coauthor of the paper. “By expanding our investigation to include more unusual formation scenarios, we’ve learned some totally new possibilities for Pluto’s evolution, which could apply to other Kuiper Belt objects as well.”

Pluto’s heart is a mixed blend

The heart, also known as the Tombaugh Regio, captured the public’s attention immediately upon its discovery. But it also immediately caught the interest of scientists because it is covered in a high-albedo material that reflects more light than its surroundings, creating its whiter color.

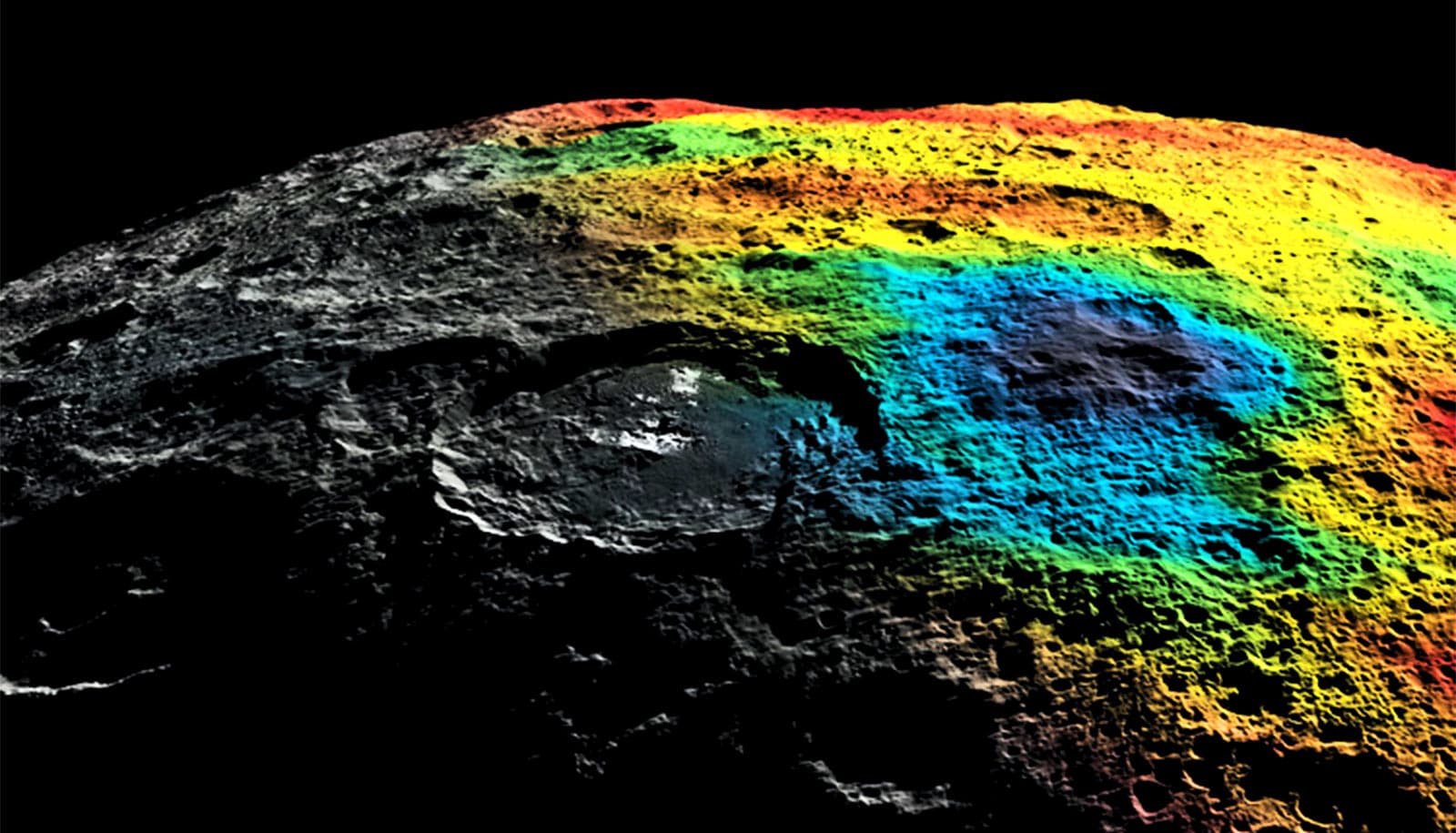

However, the heart is not composed of a single element. Sputnik Planitia covers an area of approximately 750 by 1,250 miles, equivalent to a quarter of Europe or the United States. What is striking, however, is that this region is roughly 2.5 miles lower in elevation than most of Pluto’s surface.

“While the vast majority of Pluto’s surface consists of methane ice and its derivatives covering a water-ice crust, the Planitia is predominantly filled with nitrogen ice, which most likely accumulated quickly after the impact due to the lower altitude,” says lead author Harry Ballantyne, a research associate at the University of Bern in Switzerland.

The eastern part of the heart is also covered by a similar but much thinner layer of nitrogen ice, the origin of which is still unclear to scientists, but is probably related to Sputnik Planitia.

Planetary ‘splat’

The elongated shape of Sputnik Planitia and its location at the equator strongly suggest that the impact was not a direct head-on collision but rather an oblique one, according to Martin Jutzi of the University of Bern, who initiated the study.

Like several others around the world, the team used Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics simulation software to digitally recreate such impacts, varying both the composition of Pluto and its impactor, as well as the velocity and angle of the impactor. These simulations confirmed the scientists’ suspicions about the oblique angle of impact and determined the composition of the impactor.

“Pluto’s core is so cold that the rocks remained very hard and did not melt despite the heat of the impact, and thanks to the angle of impact and the low velocity, the core of the impactor did not sink into Pluto’s core, but remained intact as a splat on it,” Ballantyne says.

This core strength and relatively low velocity were key to the success of these simulations: Lower strength would result in a very symmetrical leftover surface feature that does not look like the teardrop shape observed by NASA’s New Horizons probe during its fly-by of Pluto in 2015.

“We are used to thinking of planetary collisions as incredibly intense events where you can ignore the details except for things like energy, momentum, and density,” says coauthor Erik Asphaug, a professor at the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, whose team has collaborated with its Swiss colleagues since 2011, exploring the idea of planetary “splats” to explain, for instance, features on the far side of Earth’s moon.

“In the distant solar system, velocities are so much slower than closer to the sun, and solid ice is strong, so you have to be much more precise in your calculations. That’s where the fun starts.”

No subsurface ocean on Pluto

The current study sheds new light on Pluto’s internal structure as well. In fact, a giant impact like the one simulated is much more likely to have occurred very early in Pluto’s history than during more recent times.

However, this poses a problem: A giant depression like Sputnik Planitia is expected to slowly drift toward the pole of the dwarf planet over time due to the laws of physics, since it is less massive than its surroundings. Yet it has remained near the equator.

The previous theorized explanation invoked a subsurface liquid water ocean, similar to several other planetary bodies in the outer solar system. According to this hypothesis, Pluto’s icy crust would be thinner in the Sputnik Planitia region, causing the ocean to bulge upward, and since liquid water is denser than ice, causing a mass surplus that induces migration toward the equator.

The new study offers an alternative perspective, according to the authors, pointing to simulations in which all of Pluto’s primordial mantle is excavated by the impact, and as the impactor’s core material splats onto Pluto’s core, it creates a local mass excess that can explain the migration toward the equator without a subsurface ocean, or at most a very thin one.

Denton, who already has embarked on a research project to estimate the speed of this migration, says this novel and creative origin hypothesis for Pluto’s heart-shaped feature may lead to a better understanding of the dwarf planet’s origin.

Source: University of Arizona