Researchers have discovered a possible reason why L-dopa, the front-line drug for treating Parkinson’s disease, loses efficacy as treatment progresses.

The drug causes dyskinesia, involuntary, erratic muscle movements of the patient’s face, arms, legs, and torso.

“Paradoxically, the exact therapy that improved the quality of life for tens of thousands of Parkinson’s patients is the one that contributes to the rapid decline in quality of life over time,” says Amal Alachkar, associate professor of teaching in the University of California, Irvine’s pharmaceutical sciences department and co-corresponding author of the study. “L-dopa has been shown to accelerate disease progression through neural mechanisms that are not very well understood.”

L-dopa and other pharmacological treatments for Parkinson’s are designed to replace the lost dopamine caused by the degeneration of nerve cells in the brain. Although dopamine can’t cross the blood-brain barrier, which lets substances such as water and oxygen pass into the brain, L-dopa can, and it’s used to treat the disease’s motor symptoms.

However, 99% of L-dopa is metabolized outside the brain, so it’s administered in combination with an enzyme inhibitor to increase the amount of the dose that reaches the brain to 5 to 10% and to prevent side effects such as nausea and heart problems.

The team studied the molecular binding characteristics of L-dopa and related compounds using an optical technology called surface plasmon resonance to measure interactions between the drug and target proteins.

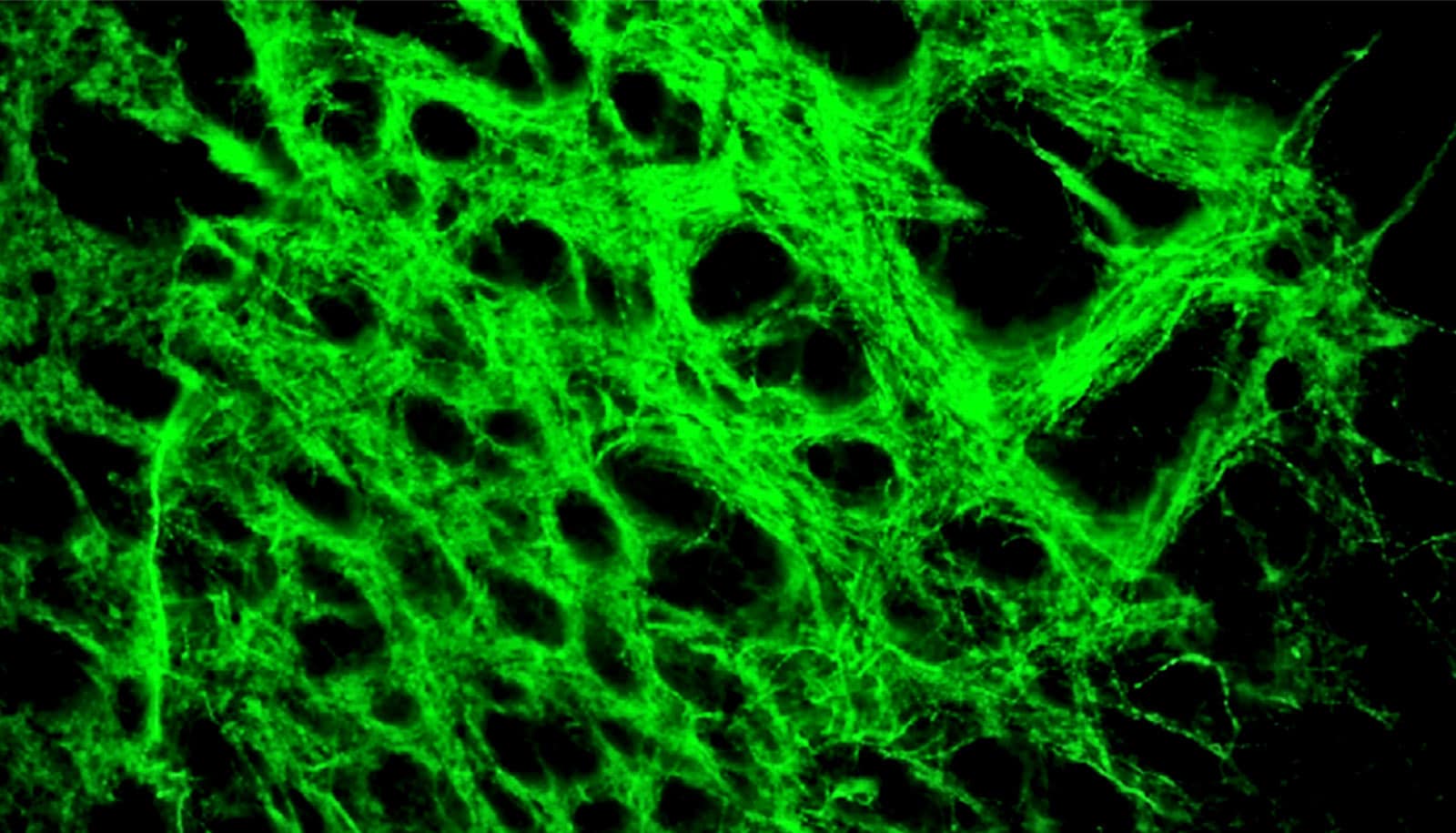

The findings of the study, which appear in ACS Chemical Neuroscience, demonstrate that L-dopa and the protein siderocalin combine in the presence of iron to create a complex that may cause a cellular iron overload, leading to an imbalance between free radicals and antioxidants, as well as neuroinflammation in the brain, triggering dyskinesia, fluctuations in mobility, and freezing episodes.

As Parkinson’s progresses, lower doses of L-dopa induce these negative side effects, while the dose required to alleviate disease symptoms increases, resulting in a narrow therapeutic window.

“This small L-dopa molecule is certainly mysterious,” Alachkar says. “We’re interested in unlocking L-dopa mysteries and, in particular, understanding how it acts as such a magic therapeutic agent and, at the same time, contributes to disease progression. The formation of the L-dopa-siderocalin complex may play a role in decreasing efficacy by reducing the amount of free L-dopa available for dopamine synthesis in the brain.”

Ongoing studies focus on testing whether continuous L-dopa administration in animal models of Parkinson’s disease is associated with increased iron accumulation in the brain’s dopaminergic neurons and if this accumulation depends on L-dopa binding to siderocalin.

Researchers also want to determine whether the complex can be detected in the blood of Parkinson’s patients, serving as a biomarker showing the correlation with their physical deterioration and as a target for new treatments for the disease.

The National Institutes of Health supported the work.

Source: UC Irvine