A new drug shows promise in treating both pancreatic cancer and triple-negative breast cancer, researchers report.

A study in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology found the drug, called ProAgio, prolonged survival in mice with pancreatic cancer.

A second study, published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, shows the drug’s effectiveness against triple-negative breast cancer, a fast-growing and hard-to-treat type of breast cancer that carries a poor prognosis.

Zhi-Ren Liu, a biology professor at Georgia State University, created ProAgio from a human protein to target the cell surface receptor integrin αVβ₃, which is expressed on cancer-associated fibroblasts.

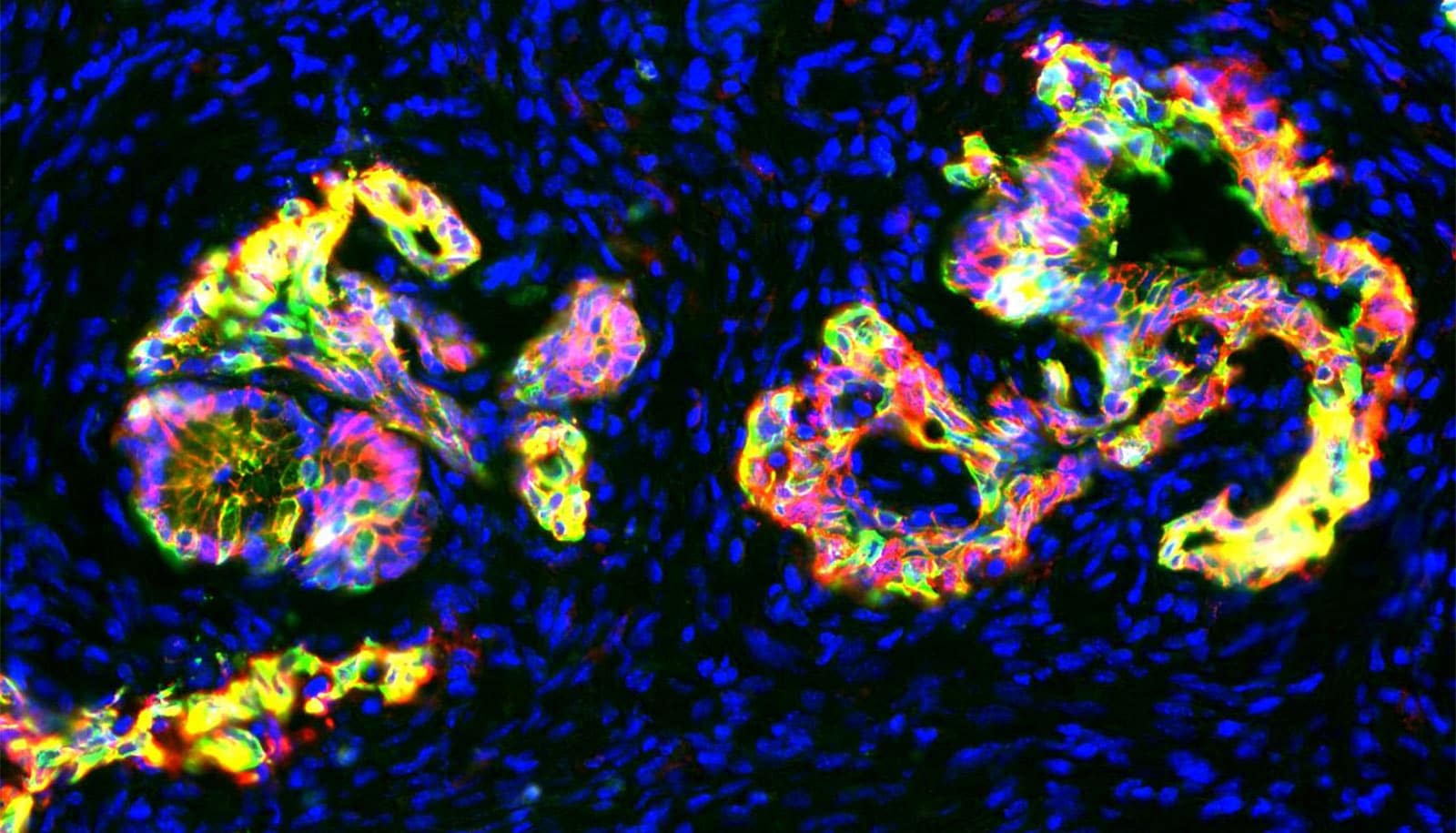

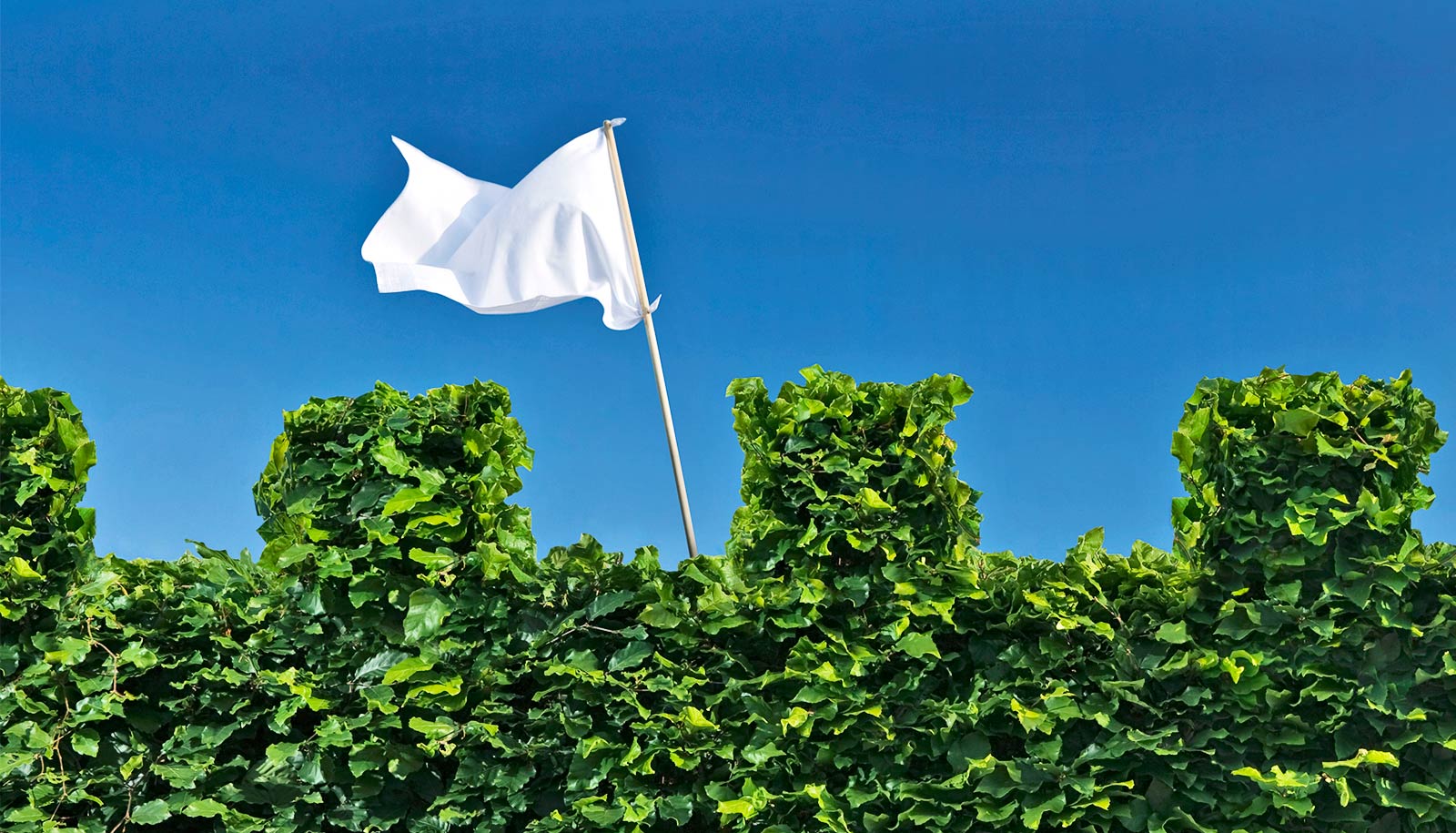

Fibroblasts are cells that generate collagen and other fibrous molecules which tumors can mobilize into service, creating a thick, physical barrier known as the stroma, which protects the cancer and helps it grow. The new drug works by inducing apoptosis, or programmed cell death, in cancer-associated fibroblasts that express integrin αVβ₃.

The dense fibrotic stroma is what makes pancreatic cancer, which has a five-year survival rate of just 8%, so lethal and difficult to treat. Among triple-negative breast cancer patients, research shows denser stroma is associated with poorer survival and high recurrence rates.

“All solid tumors use cancer-associated fibroblasts, but in pancreatic cancer and triple-negative breast cancer, the stroma is so dense there’s often no way for conventional drugs to penetrate it and effectively treat the cancer,” Liu says.

The stroma also helps the tumor hide from your body’s immune system. Immunotherapy, a type of treatment that uses your immune system to fight cancer, is less effective against tumors protected by a dense stroma that is rich in cancer-associated fibroblasts.

Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote angiogenesis, or the development of new blood vessels. Angiogenesis plays an important role in the spread of cancer because solid tumors need a blood supply to grow.

In both studies, Liu and his team show ProAgio has a profound effect on tumor vasculature. In the case of pancreatic cancer, it reopened blood vessels that had collapsed due to high extravascular stress caused by the dense stroma. In the case of triple-negative breast cancer, the drug’s anti-angiogenic activity reduced irregular, leaky angiogenic tumor vessels. In both cases, ProAgio allowed drugs to effectively reach the cancer.

The drug is unique in that it targets only cancer-associated fibroblasts—a subclass of the cells that is actively engaged in supporting cancer—rather than inactive fibroblasts. This reduces side effects of the drug and increases its effectiveness.

“When you have a wound, for example, normal fibroblasts will secrete fibers to limit the damage and promote healing,” says Liu. “The tumor region is basically a wound that won’t heal. Quiescent fibroblasts may play a role in preventing cancer from spreading. You don’t want to kill the good guys, only the bad guys.”

ProAgio is licensed to ProDa BioTech, a pharmaceutical research company Liu founded. In 2018, ProDa BioTech received $2 million from the National Cancer Institute to fund toxicology and pharmacokinetic studies that are required before moving the drug to early-stage clinical trials.

Those studies have been completed and the company has submitted an Investigational New Drug (IND) Application, a request for authorization from the Food and Drug Administration to administer ProAgio to human subjects.

Once the IND is granted, Liu says the immediate next step is to begin clinical trials. The first trial, to determine patient tolerability and recommended phase II dose, will begin early this year at the National Institute of Health Clinical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. Christine Alewine, an oncologist at the National Cancer Institute will lead the trial. In late 2021, Emory University is set to begin a multi-site trial among breast cancer and pancreatic cancer patients.

Source: Georgia State University