Eastern oysters and three species of clams can flourish when farmed together, potentially boosting profits of shellfish growers, a new study shows.

Though diverse groups of species often outperform single-species groups, most bivalve farms in the US and around the world grow their crops as monocultures, researchers say.

“Farming multiple species together can sustain the economic viability of farm operations and increase profitability by allowing shellfish growers to more easily navigate market forces if the price of each individual crop fluctuates,” says lead author Michael P. Acquafredda, a doctoral student based at Rutgers University’s Haskin Shellfish Research Laboratory and lead author of the paper in the journal Marine Ecology Progress Series.

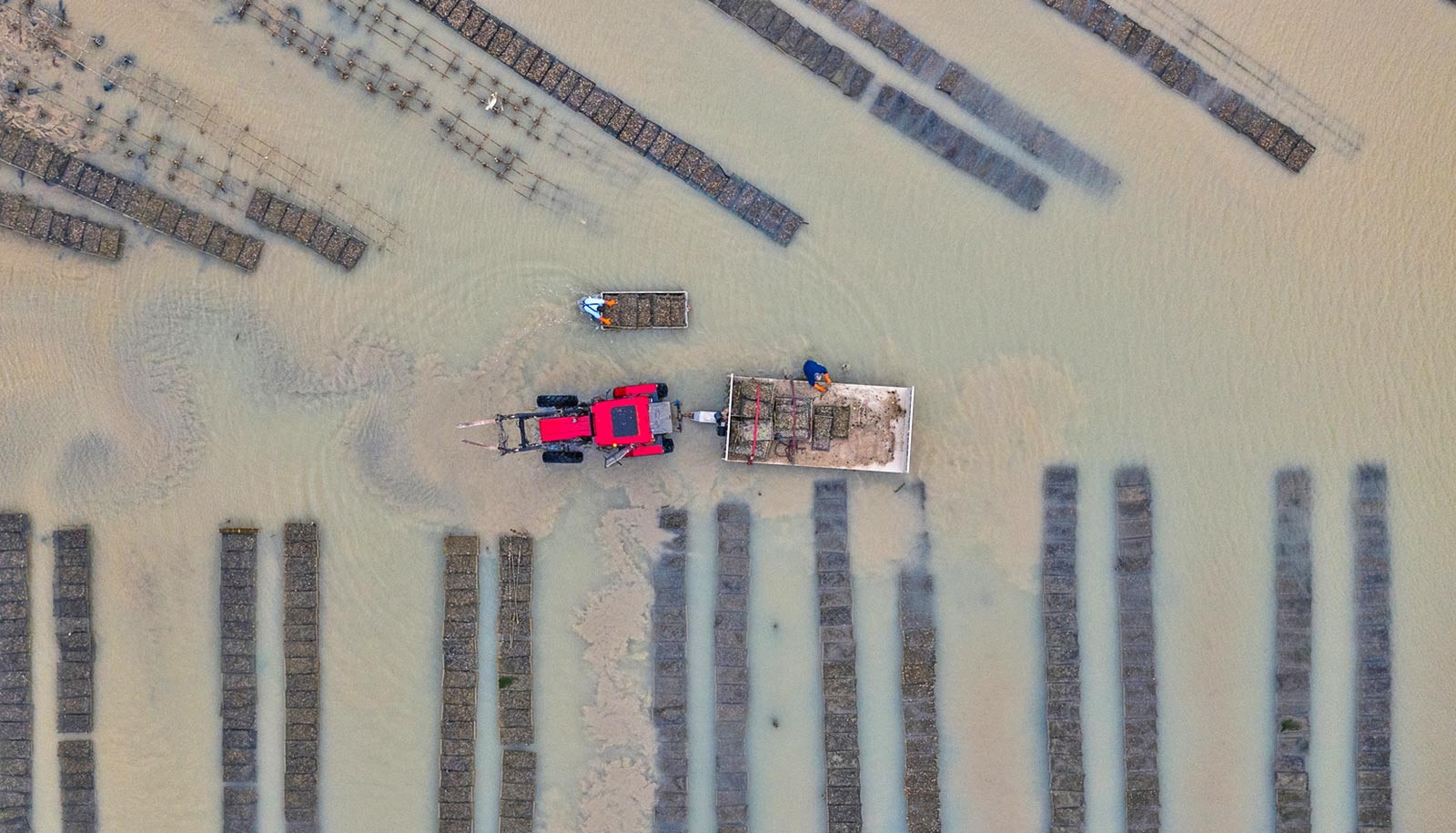

Farming mollusks such as clams, oysters, and scallops contributes billions of dollars annually to the world’s economy. In the United States, farmers harvested more than 47 million pounds of clam, oyster, and mussel meat worth more than $340 million in 2016.

The study, which took place in a laboratory setting at Rutgers’ New Jersey Aquaculture Innovation Center tested the feasibility of farming multiple bivalve species in close proximity to each another.

Mimicking farm conditions, the study examined the filtration rate, growth, and survival of four economically and ecologically important bivalve species native to the northeastern United States: the Eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica); Atlantic surfclam (Spisula solidissima); hard clam (Mercenaria mercenaria); and softshell clam (Mya arenaria).

When supplied with seawater containing naturally occurring algal particles, the groups that contained all four species removed significantly more particles than most monocultures. This suggests that each species prefers to filter a particular set of algal food particles.

“This shows that, to some degree, these bivalve species complement each other,” says coauthor Daphne Munroe, an associate professor in the marine and coastal sciences department in the School of Environmental and Biological Sciences.

The scientists also found virtually no differences in growth or survival for any of the four species, suggesting that when food is not an issue, farmers can raise these bivalves together and not worry about them outcompeting each another.

“This study illustrates the benefits of diversifying crops on shellfish farms,” Acquafredda says. “Crop diversification gives aquaculture farmers protection from any individual crop failure, whether it’s due to disease, predation or fluctuating environmental conditions.

“In future studies, the feasibility of bivalve polyculture should be tested on commercial bivalve farms.”

Source: Rutgers University