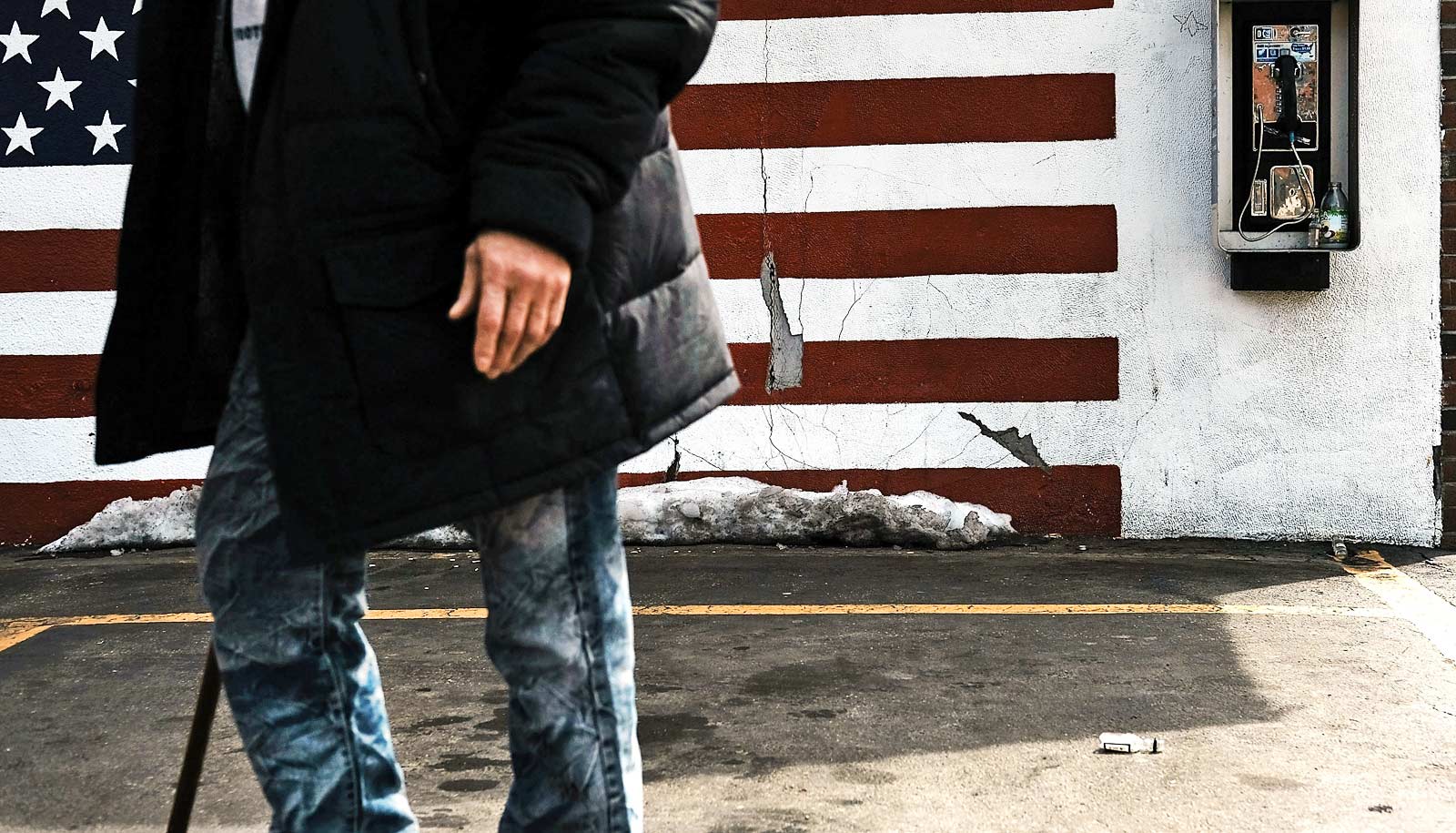

Suicides and drug overdoses kill American adults at twice the rate today as they did just 17 years ago. Opioids are a key contributor to that rise, a new study shows.

Reversing this deadly double trend will take investment in programs proven to prevent and treat opioid addiction, experts say.

Experts need to identify who’s most at risk of deliberate or unintentional opioid overdoses, so they get better pain management, mental health care, and medication-assisted therapy for addiction.

According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, the number of deaths from suicides and unintentional overdoses together rose from 41,364 in the year 2000 to 110,749 in 2017. Researchers calculated a rate per 100,000 Americans to account for the rise in total population during that time and found that the rate of the two causes of death rose from 14.7 to 33.7.

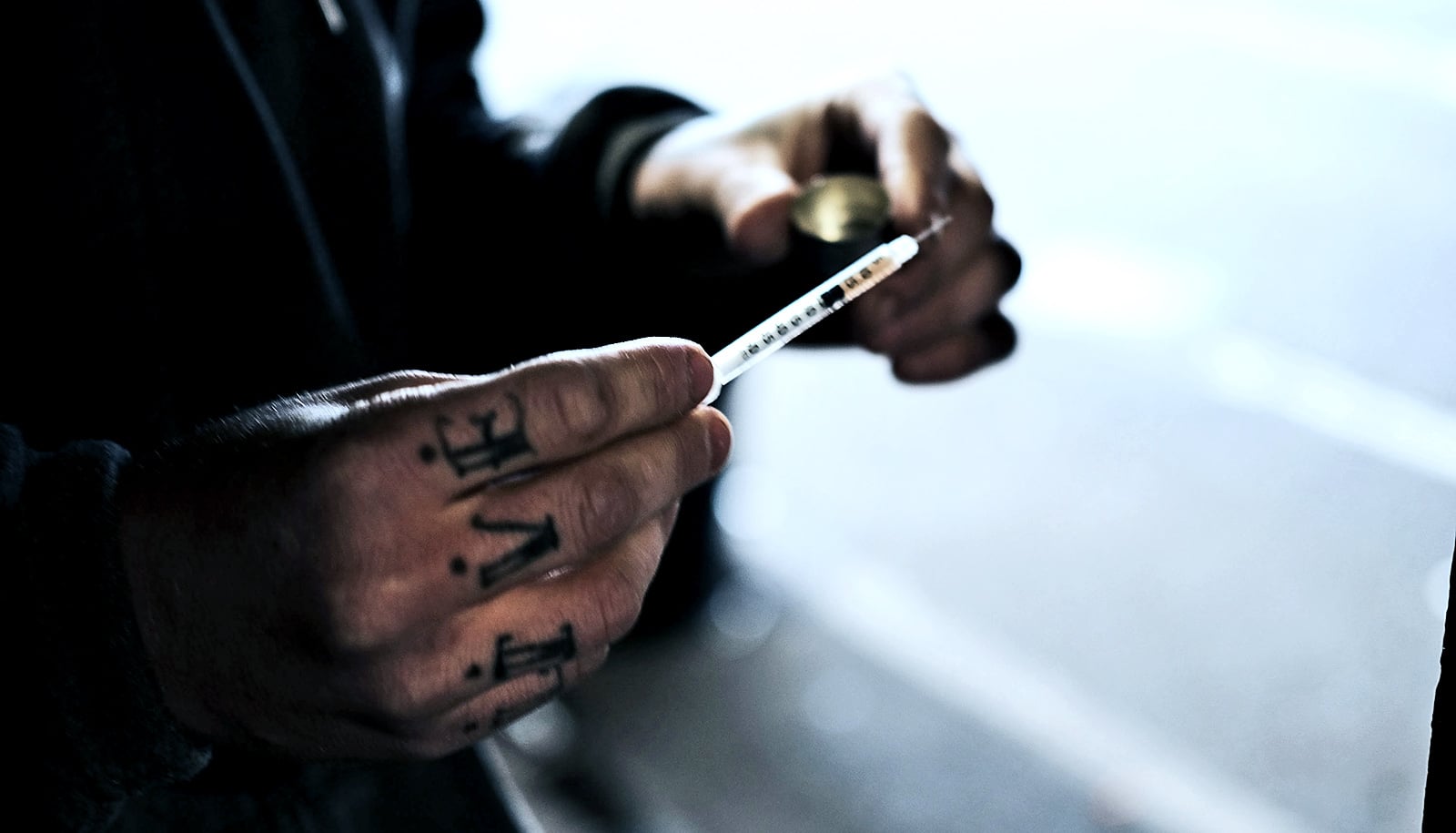

When researchers drilled down to include just opioid-caused suicides and overdoses, they accounted for more than 41 percent of deaths in 2017, up from 17 percent in 2000. Opioids were implicated in more than two-thirds of all unintentional overdose deaths in 2017, and one-third of all overdose-related suicides.

Prescriptions and street drugs

For the paper, which appears in the New England Journal of Medicine, researchers reviewed evidence around the links among overdoses, suicides, chronic pain, and opioids of all kinds, including those prescribed by doctors and the kinds bought on the street.

They also looked at current evidence to determine what best identifies risk of suicide or overdose, and how best to treat people with chronic pain, opioid use disorders, and mental health conditions.

“Unlike other common causes of death, overdose and suicide deaths have increased over the last 15 years in the United States,” says Amy Bohnert, associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Michigan Medical School who co-directs the University of Michigan Program for Mental Health Innovation, Services, and Outcomes.

“This pattern, along with overlap in the factors that increase risk for each, support the idea that they are related problems and the increases are due to shared fundamental causes.”

The rise in overdose and suicide death rates over the past two decades paralleled the rise in opioid painkiller prescriptions, and later the rise in use of heroin and illegally manufactured fentanyl.

The researchers looked at the competing theories of whether an increased supply of opioids from legal and illegal sources, or an increased demand for them because of social and economic factors, were more likely to be to blame. Though some evidence suggests that the “supply” theory has more support for overdose, both theories have validity and deserve to be addressed through policy solutions, they say.

Because of the common factors involved, increased use of proven prevention and treatment strategies may offer a way to reduce the death toll from both overdose and suicide, the researchers say.

Who’s most at risk

For both suicide and unintentional overdose, men had death rates twice as high as women in 2017, according to CDC data. Rates of suicide deaths were highest for white men and American Indian/Alaska Native men, and lower across the board for women.

White men under age 40 had the highest rate of unintentional overdoses, with nearly 50 deaths per 100,000. But the rate among black men rose in middle and older age, surpassing that of white and Native American men.

Unintentional overdose death rates were much higher than suicide rates among white, black, and Native American women younger than 65. But research on racial biases among medical examiners in ruling deaths as suicides or overdoses may be a factor in those findings.

“Individuals with chronic pain are at clear elevated risk for both unintentional overdose and suicide, says Mark Ilgen, a psychiatry professor and an associate director of the University of Michigan Addiction Center.

“To date, many system-level approaches to address overdose and suicide have addressed these as if they are unrelated outcomes. Our goal was to highlight the fact that these adverse outcomes likely go together and effective efforts to help those with pain will likely need to simultaneously consider both overdose and suicide risk.”

Necessary interventions

Several interventions could bring down the risk of suicide or overdose among those most at risk, the researchers say.

For instance, people who are on high-dose regimens of prescription opioids, or who are showing signs of prescription opioid misuse, could receive guidance through a slow, patient-centered tapering of their opioid use.

Reducing prescription opioid doses gradually may actually reduce patients’ pain, and reducing the amount of opioid painkillers prescribed at any given time could also help keep at-risk patients from having the means of suicide or unintentional overdose on hand.

Also, naloxone, which can reverse an opioid overdose, should be prioritized for the friends and family of such patients and anyone with an opioid use disorder should have greater availability to medication-assisted treatment, including the use of methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone given in concert with counseling.

“Medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorders have been repeatedly proven to reduce overdose deaths relative to no treatment or non-medication treatment,” says Bohnert. “Reducing the severity of opioid use disorder through medications will also improve mental health. Reducing barriers to use of these medications is essential to addressing both overdose and suicide.”

Source: University of Michigan