Researchers have merged the ancient art of origami with 21st century technology to create a one-step approach to fabricating complex structures whose light weight, expandability, and strength could have a variety of applications, including biomedical devices and equipment used in space exploration.

Until now, making such structures has involved multiple steps, more than one material, and assembly from smaller parts.

“What we have here is the proof of concept of an integrated system for manufacturing complex origami. It has tremendous potential applications,” says Glaucio H. Paulino, professor at the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Georgia Institute of Technology.

Zippered tubes

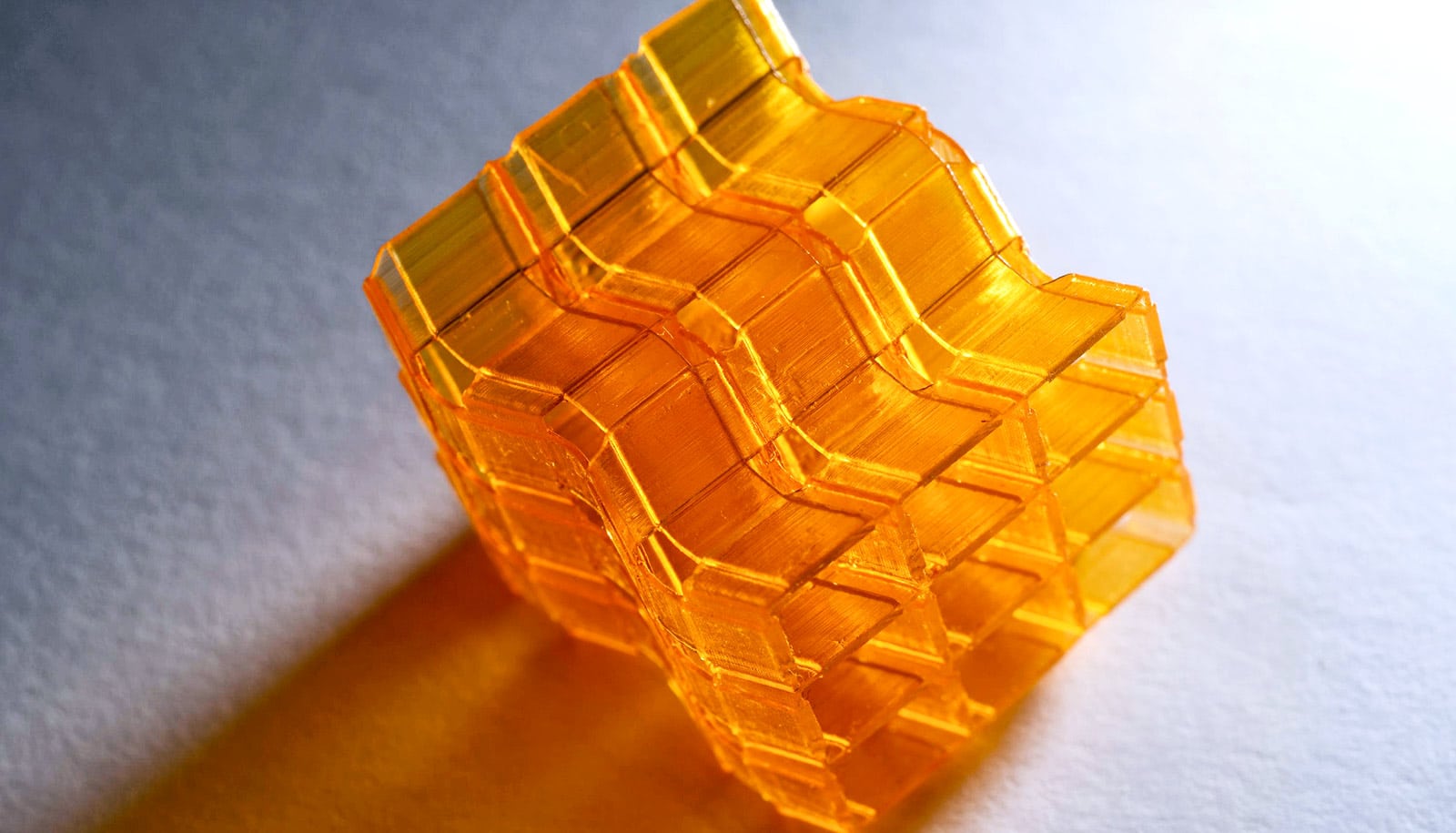

Researchers used a relatively new kind of 3D printing called Digital Light Processing (DLP) to create origami structures that are not only capable of holding significant weight but can also fold and refold repeatedly in an action similar to the slow push and pull of an accordion.

When Paulino first reported these structures, or “zippered tubes,” in 2015, they were made of paper and required gluing. In the current work, the zippered tubes—and complex structures made out of them—are composed of one plastic (a polymer) and don’t require assembly.

There are many different types of 3D printing technologies. The most familiar, inkjet, has been around for some 20 years. But until now, it has been difficult to create 3D-printed structures with the intricate hollow features associated with complex origami because removing the supporting materials necessary to print these structures is challenging.

Further, unlike paper, researchers could not fold the 3D-printed materials could numerous times without breaking them.

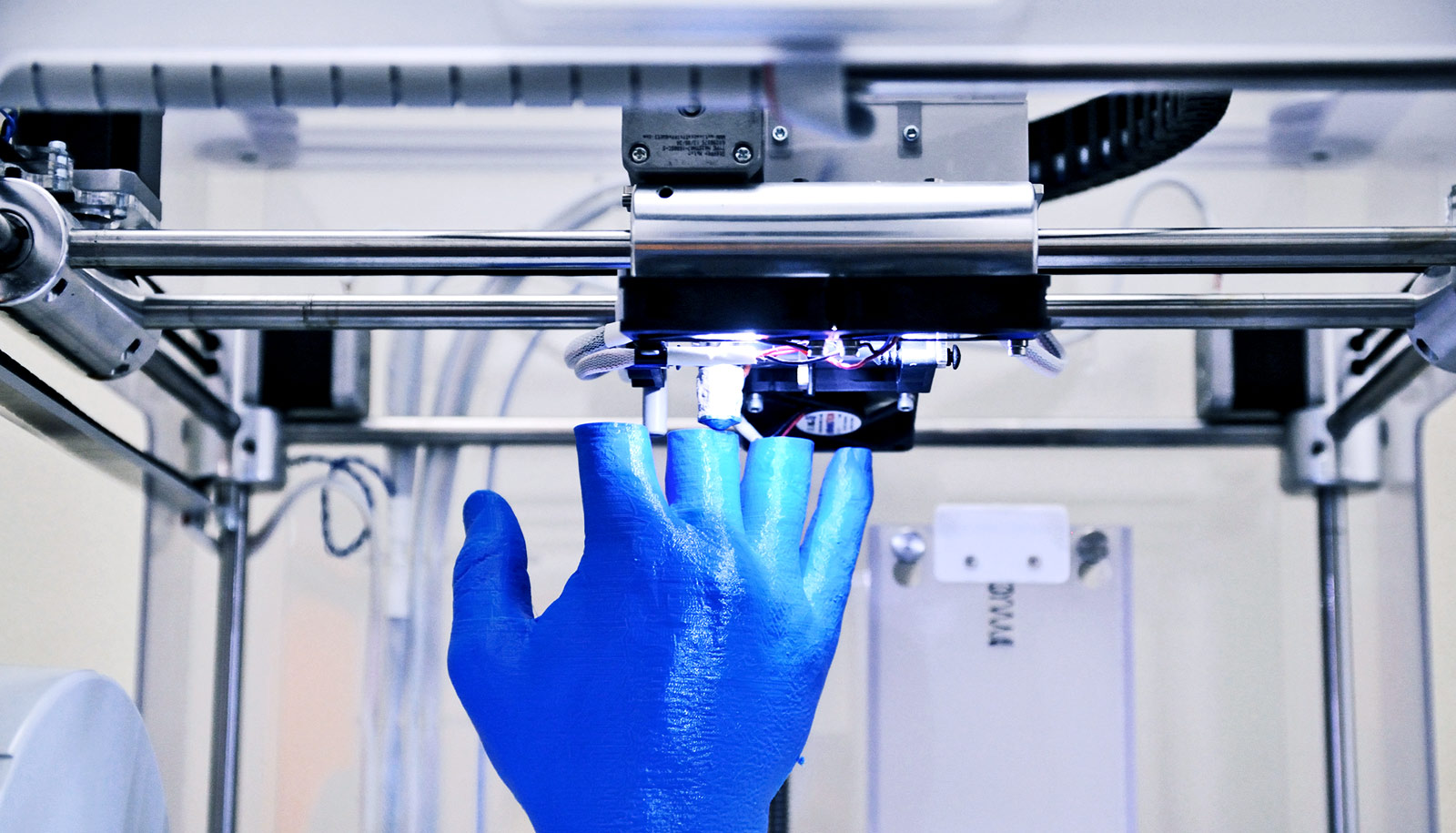

Enter DLP and some creative engineering. According to H. Jerry Qi, a faculty fellow in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering, DLP has been in the lab for a while, but commercialization only began about five years ago. Unlike other 3D printing techniques, it creates structures by printing successive layers of a liquid resin that ultraviolet light then cures, or hardens.

Strong and resilient

For the current work, which appears in Soft Matter, researchers first developed a new resin that, when cured, is very strong.

“We wanted a material that is not only soft, but can also be folded hundreds of times without breaking,” Qi says.

The resin, in turn, is key to an equally important element of the work: tiny hinges. These hinges, which occur along the creases where the origami structure folds, allow folding because they are made of a thinner layer of resin than the larger panels of which they are part. (The panels make up the bulk of the structure.)

Together the new resin and hinges worked. The team used DLP to create several origami structures including the individual origami cells that compose the zippered tubes and a complex bridge composed of many zippered tubes.

The researchers subjected all of them to tests that showed they were not only capable of carrying about 100 times the weight of the origami structure, but also that researchers could repeatedly fold and unfold them without breaking.

“I have a piece that I printed about six months ago that I demonstrate for people all the time, and it’s still fine,” Qi says.

What’s next?

Among other things, Qi is working to make the printing even easier while also exploring ways to print materials with different properties. Meanwhile, Paulino’s team recently created a new origami pattern on the computer that he is excited about but that he has been unable to physically make because it is so complex. “I think the new system could bring it to life,” he says.

Additional authors are from Georgia Tech, Peking University, and the Beijing Institute of Technology.

The Air Force Office of Scientific Research, the National Science Foundation, the Raymond Allen Jones Chair at Georgia Tech, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, and the National Materials Genome Project of China funded the work.

Source: Georgia Tech