New research suggests the innate immune system remembers foreign cells.

The finding could pave the way to drugs that lengthen long-term survival of organ transplants, researchers say.

Chronic rejection of transplanted organs is the leading cause of transplant failure, and one that the field of organ transplantation has not overcome in almost six decades since the advent of immunosuppressive drugs enabled the field to flourish.

“The rate of acute rejection within one year after a transplant has decreased significantly, but many people who get an organ transplant are likely to need a second one in their lifetime due to chronic rejection,” says co-senior author Fadi Lakkis, chair in transplantation biology and scientific director of the University of Pittsburgh’s Thomas E. Starzl Transplantation Institute.

“The missing link in the field of organ transplantation is a specific way to prevent rejection, and this finding moves us one step closer to that goal.”

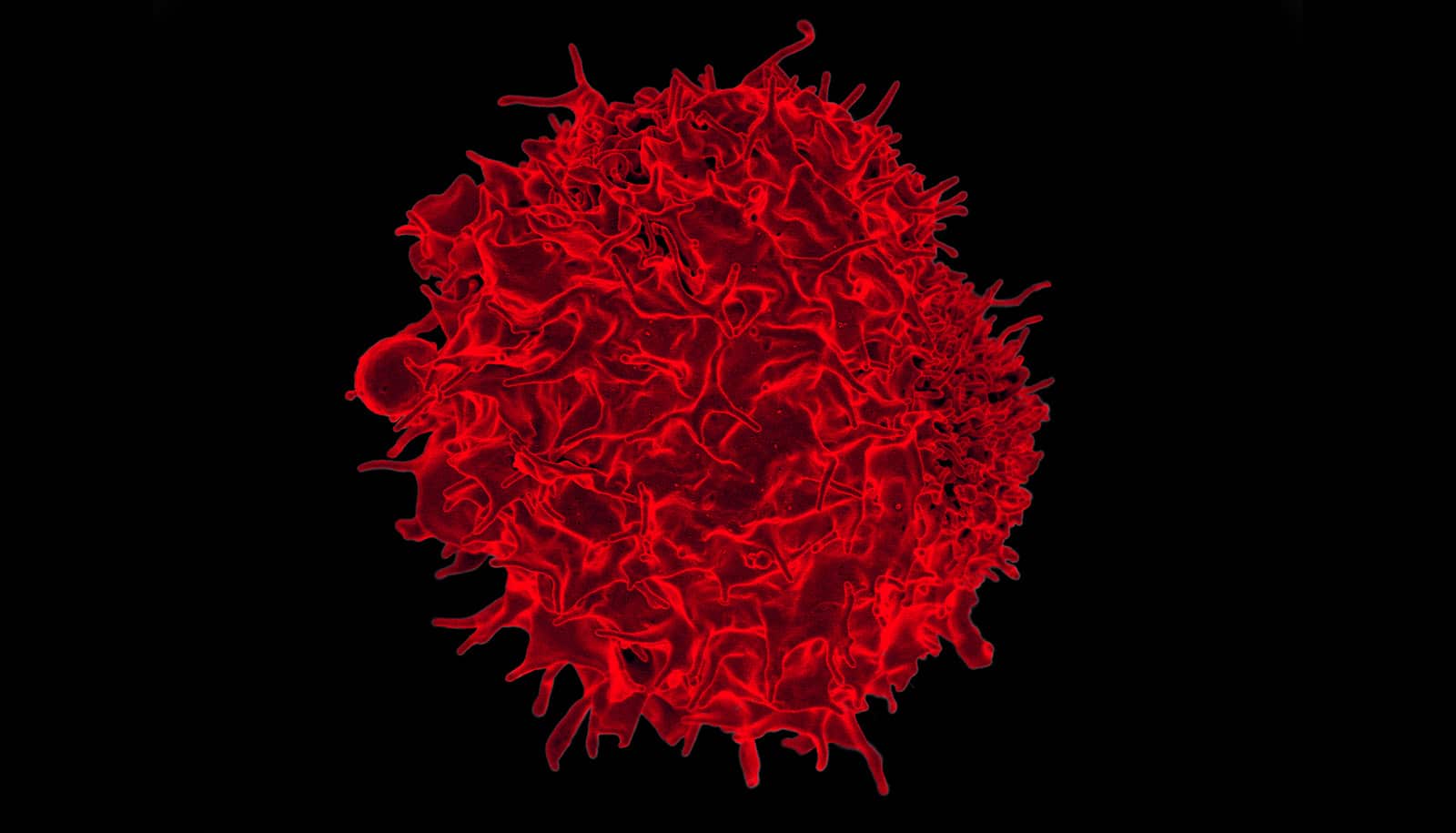

The immune system is composed of innate and adaptive branches. The innate immune cells are the first to detect foreign organisms in the body and are required to activate the adaptive immune system.

Researchers had thought immunological “memory”—which allows our bodies to remember foreign invaders so they can fight them off more quickly in the future—was unique to the adaptive immune system.

Vaccines, for example, take advantage of this feature to provide long-term protection against bacteria or viruses. Unfortunately, this very critical function of the immune system is also why transplanted organs are eventually rejected, even in the presence of immune-suppressing drugs.

In the new study in Science, researchers used a genetically modified mouse organ transplant model to show that the innate immune cells, once exposed to a foreign tissue, could remember and initiate an immune response if exposed to that foreign tissue in the future.

“Innate immune cells, such as monocytes and macrophages, have never been thought to have memory,” says senior author Martin Oberbarnscheidt, assistant professor of surgery. “We found that their capacity to remember foreign tissues is as specific as adaptive immune cells, such as T cells, which is incredible.”

The researchers then used molecular and genetic analyses to show that a molecule called paired Ig-like receptor-A (PIR-A) was required for this recognition and memory feature of the innate immune cells in the hosts. When researchers either blocked PIR-A with a synthetically engineered protein or genetically removed it from the host animal, the memory response was eliminated, allowing transplanted tissues to survive for much longer.

“Knowing exactly how the innate immune system plays a role opens the door to developing very specific drugs, which allows us to move away from broadly immunosuppressive drugs that have significant side effects,” says Lakkis.

The finding has implications beyond transplantation, according to Oberbarnscheidt. “A broad range of diseases, including cancer and autoimmune conditions, could benefit from this insight. It changes the way we think about the innate immune system.”

Additional researchers are from Houston Methodist Hospital and the University of Pittsburgh. The National Institutes of Health and the University of Pittsburgh supported the work.

Source: University of Pittsburgh